Unconventional phosphoinositide synthesis

Salmonella and Shigellabacteria cause or contribute to human diseases ranging from acute food poisoning to life-threatening typhoid fever and gall bladder cancer. Both are on a World Health Organization list of priority pathogens for developing new antibiotics. To help combat the effects of these bacteria, our lab is studying the way they synthesize the tiny lipids known as 3-phosphoinositides to hijack host.

These two bacteria can inject bacterial proteins called effectors into target human cells, allowing them to acquire nutrients and reproduce in the cell. Researchers have described one such effector in Salmonella, SopB, and its homolog in Shigella, IpgD, as phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, or PI(4,5)P2, phosphatases. These phosphatases deplete PI4,5P2, an important lipid in human cells for proper actin dynamics, endocytosis and ion channel regulation.

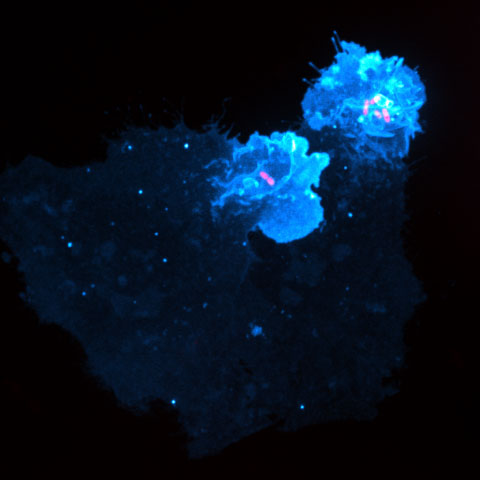

Although they deplete PI4,5P2, these bacterial phosphatases increase two other phosphoinositides, PI3,4P2 and PI3,4,5P3. Production of these two lipids stimulates the activation of small GTPases, including Rac1 and Cdc42, that induce robust and localized plasma membrane ruffling near the site of bacterial attachment. Ultimately, the bacteria invade and hijack the host cells. Production of PI3,4P2 and PI3,4,5P3 also promotes the survival of the now-infected cell by activating the serine/threonine protein kinase Akt and other downstream pathways.

How could a phosphatase seemingly increase the levels of phosphoinositides typically produced by kinases? For years, researchers thought that SopB and IpgD somehow were activating multiple host phosphoinositide 3-kinases, or PI3Ks. Inhibiting individual PI3Ks did not prevent the function of the effectors and the production of PI3,4P2 and PI3,4,5P3. Could the ability to produce PI3,4P2 and PI3,4,5P3 be intrinsic to SopB and IpgD? In support of this notion, researchers established that the catalytic cysteine residue in the active site was required for both the reduction of PI4,5P2 and the production of PI3,4P2/PI3,4,5P3.

SopB and IpgD are homologs of human phosphoinositide phosphatases, such as synaptojanin and INPP4B, that are related to the larger family of protein tyrosine phosphatases. These phosphatases contain active cysteine residues, and as part of the enzymatic cycle, there is a cysteine–phosphate intermediate that then is hydrolyzed by water. SopB and IpgD operate on the membrane surface, raising the possibility that another lipid, not water, could attack the cysteine–phosphate intermediate. In this situation, the effector would behave as a phosphotransferase and not a phosphatase.

Armed with this hypothesis, we demonstrated that SopB could generate PI3,4,5P3/PI3,4P2 in a test tube when supplied with only PI4,5P2 as a substrate. SopB is a very active phosphatase; if given enough time, the phosphoinositides are reduced to PI and the free inorganic phosphate. Given the redundancy of PI3Ks in mammalian cells, we used baker’s yeast, which naturally lacks class I and II PI3Ks and remains viable even when the sole class III PI3K is inactivated. When we introduced SopB into these mutant yeast cells, which contain ample amounts of PI4,5P2 but no PI3K activity, PI3,4P2 was formed.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Defining JNKs: Targets for drug discovery

Roger Davis will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award in Biomedical Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Building better tools to decipher the lipidome

Chemical engineer–turned–biophysicist Matthew Mitsche uses curiosity, coding and creativity to tackle lipid biology, uncovering PNPLA3’s role in fatty liver disease and advancing mass spectrometry tools for studying complex lipid systems.

Redefining lipid biology from droplets to ferroptosis

James Olzmann will receive the ASBMB Avanti Award in Lipids at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Life in four dimensions: When biology outpaces the brain

Nobel laureate Eric Betzig will discuss his research on information transfer in biology from proteins to organisms at the 2026 ASBMB Annual Meeting.