What makes lager yeast special? Inside the genetics of beer

While beers such as ales, stouts and sours have their own fanbases, America has long favored a crisp, refreshing lager. But what makes a yeast variety suitable for light, lager beer rather than ales?

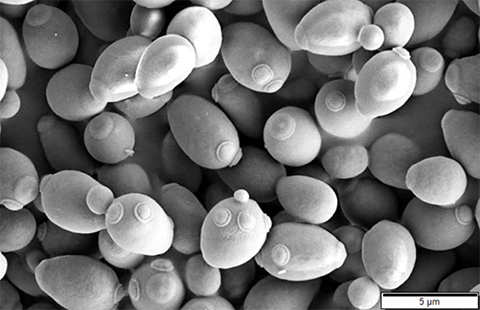

According to Chris Todd Hittinger, a professor of genetics evolution at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, or baker’s yeast, requires a warm environment for optimal fermentation. This works well for brewing heavier beers, such as ales. However, to produce a lager, brewers need yeast that ferments best at cool temperatures.

Industrial lager brewers favor S. pastorianus, a hybrid of S. cerevisiae and a wild ancestor. Scientists did not understand how S. cerevisiae evolved to give rise to a cold-dwelling species until they discovered the wild ancestor of lager yeast, S. eubayanus, in 2011.

To understand this evolution, Hittinger’s lab compared the genomes of S. cerevisiae and S. eubayanus and found that S. eubayanus acquired cold tolerance in part through its mitochondrial genome.

“When we do experiments where we take a strain of industrial lager yeast, all of which have the S. eubayanus mitochondrial genome, and swap in the S. cerevisiae mitochondrial genome, the temperature preference of the yeast shifts upwards,” Hittinger said. “We think this is one of the big smoking guns, and it explains why all industrial lager strains have an S. eubayanus mitochondrial genome.”

Sugar, sugar, sugar

Beer starts with three main components: hops, yeast and wort — a sugary grain water that contains maltose and maltotriose.

“Unless you like cloyingly sweet beers ... you need to ferment all of the fermentable sugars into carbon dioxide and ethanol to create a nice, crisp, dry lager you’d enjoy on a hot summer day,” Hittinger said.

Domesticated lager yeasts can ferment maltotriose, but S. eubayanus cannot. Hittinger, John Crandall, a Ph.D. student in the Hittinger lab, and collaborators performed adaptive evolution experiments to find out how S. eubayanus could have acquired this trait. They found two distinct mechanisms.

“Both of our studies show that it takes pretty dramatic mutations to evolve this key trait,” Crandall said.

When selecting for maltotriose use, they found S. eubayanus acquired a novel, chimeric maltotriose transporter via genetic recombination of two MALT genes, which alone drive maltose metabolism.

Conversely, when they performed experiments selecting for maltose use, they found that the mutant S. eubayanus changed from diploid to haploid. This change activated an alternative metabolism in the yeast cells, allowing a haploid-specific gene to activate a previously dormant sugar transporter.

“Most of the advantage that haploids have comes from the fact that they express a small set of haploid-specific genes, which defines their cell type,” Crandall said. “None of these (haploid) genes were known to have any regulatory crosstalk with metabolic pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, where that cell type–specification circuit has been extensively studied.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

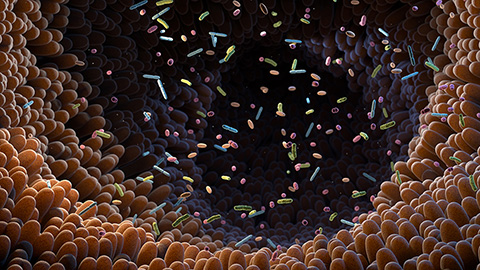

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

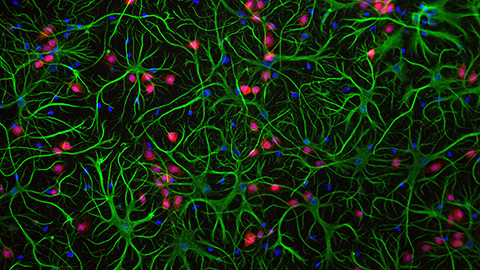

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.