Prion origins are key in study of chronic wasting disease

Chronic wasting disease, or CWD, is a contagious and fatal prion disorder that affects cervid species such as deer, elk, caribou, reindeer and moose. Cervids of all ages, captive and wild, can be affected.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that CWD is prominent in the continental U.S., Canada, Norway, Finland, Sweden and South Korea. Increased prevalence and spread of CWD endangers cervid populations in these regions. No vaccine or treatment exists.

Like any prion disease, CWD is characterized by the misfolding of a normal protease-sensitive host protein, or PrPC, to a protease-resistant isoform, or PrPSc. The misfolded pathogenic PrPSc has distinct biochemical profiles that correlate with specific disease characteristics. CWD spreads when PrPSc is shed into the environment through urine, feces, bodily fluids or carcasses or by direct animal-to-animal contact.

Mark Zabel leads a team at Colorado State University that studies prion diseases.

“Chronic wasting disease can have serious consequences,” he said. “In Colorado and Wyoming, where the disease was first discovered, prevalence rates in specific herds are estimated to be between 30% and 50%. This rate in population decline can lead to local extinction of cervid species.”

Although CWD is a neurodegenerative disease, in cervids, PrPSc proteins are primarily of lymphogenic origin. Once PrPSc enters the body via oral or intranasal ingestion, it is replicated in the retropharyngeal lymph nodes, or LN. The PrPSc eventually accumulates in the obex, a region in the medulla of the central nervous system, or CNS, resulting in wasting and spongiform encephalopathy.

Typical of prion diseases, CWD is neurological, and the CNS has the highest prion concentration, so research has focused on brain-derived prions. However, the infectious prions shed in CWD primarily originate in the lymphoreticular system.

In a recent article in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, Zabel’s team reports differences in the biochemical profiles of prion strains of lymphogenic and neurogenic origins in free-ranging white-tailed deer.

Zabel and his team report that paired obex and LN-derived prions from the same animal showed no significant differences in conformational stability, nor was interanimal variation within the same tissue substantial.

Glycoform ratio analysis showed differences in glycosylation patterns in prions derived from the obex and LN in the same animal. To the team’s surprise, LN-derived glycosylation patterns showed only marginal differences among animals, but brain-derived prions showed significant differences.

Using an ELISA-based structural profiling assay, the authors also saw greater conformational diversity in LN-derived prions than brain-derived prions.

“Prions that exist in infected animals are typically not a singular species but a sort of quasi-species or a cloud of different subspecies,” Zabel said. “We would argue that predominant species are selectedinside the animal from a large pool of diverse prions.”

Based on their observations, the authors propose that predominant isoforms of neurogenic PrPSc are selected by the brain from a larger pool of LN-derived PrPSc. The neurogenic prion strains selected can vary considerably from animal to animal.

Extraneural prion strains shed into the environment may have a lower species barrier than neurogenic prions. The ability to transmit infectious prions between species increases the zoonotic potential, or the ability to infect humans, of CWD. The study underscores the importance of including strain properties alongside prion positivity as a criterion for diagnostic tests used by wildlife management agencies.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

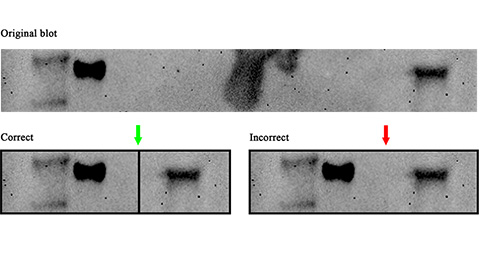

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.