Health journey helps researcher teach old mice new tricks

Eileen Parks’ diagnosis led to hours of midnight reading, years in the lab and, recently, a discovery that improves our understanding of cognitive changes with age.

“I have a very specific type of epilepsy,” the Oklahoma University graduate student explained. “My seizures are controlled now by medication. But my science brain wanted to understand (why) … I can only have a seizure during the second or third day of my menstrual period.”

For about one in three women with epilepsy, the odds of having a seizure fluctuate in synchrony with their menstrual cycle — more specifically, with progesterone. Parks calls progesterone “the master hormone” because enzymes can convert it into other hormones and metabolites with diverse biological activity. One of those, allopregnanolone, piqued her interest.

“If I’m curious about something, I will literally spend all night on my computer reading everything I could find out about it,” Parks said. She learned that allopregnanolone tends to suppress seizures because it binds to and affects the activity of a receptor for the neurotransmitter GABA, or gamma-aminobutyric acid. GABA-responsive neurons, which generally inhibit other neurons’ activity, can help dial back the excessive stimulation thought to lead to epilepsy.

Her dogged curiosity carried Parks into a graduate research fellowship in the lab of Bill Sonntag, an Oklahoma University Health Sciences Center professor who studies the impacts of aging on the brain. Parks’ interest did not fit perfectly into the lab’s research, but Sonntag told her she had a legitimate question; very little was known about how allopregnanolone alters during aging.

“It’s reduced in all these disease models: epilepsy, PTSD, Alzheimer’s,” Parks said. “But only a few studies have really investigated its levels in normal aging.” None, she added, had looked at the regulation of allopregnanolone synthesis in the aging brain.

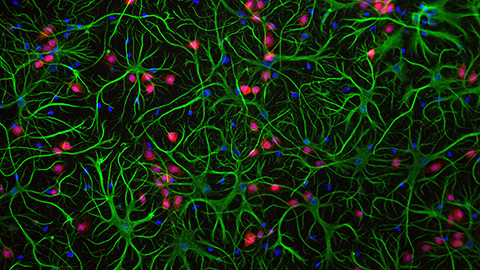

By the end of a mouse’s two-year lifespan, it becomes as forgetful as a human many decades older. An old mouse takes longer than its young peers to learn where it can climb out of a water maze or which of three doors it must pass through to receive a food pellet. Parks, Sonntag and colleagues showed that that decline in sharpness correlated with a decline in allopregnanolone.

Younger mice learned faster; older mice more slowly. But when the older mice received a booster dose of allopregnanolone, that gap shrank. The team then found that giving young mice an infusion of the inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 or blocking its activity in older mice also could reduce the gap.

That meant the changes were caused by increasing inflammation. As they grew older and accumulated the inflammatory molecule interleukin-6, mice made less of the enzymes that convert progesterone to allopregnanolone. Meanwhile, they made more of the enzymes that convert progesterone into corticosteroids associated with stress — another known facet of aging. “This is a phenomenon we’re aware of that happens with age,” Sonntag said. “The increase in glucocorticoids has been investigated a lot” and linked to inflammation.

In their recent paper in the Journal of Lipid Research, the team left open the question of how allopregnanolone improves cognition. But they have hypotheses: Perhaps, by altering GABA receptor function, allopregnanolone affects the birth of new neurons, which require GABA. Or the hormone might alter the way that neurons use energy, as it’s known to affect mitochondrial function.

In any case, asking about allopregnanolone worked out. “I have one of those personalities where I get really fixated on things,” Parks said. “In this case, it paid off.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

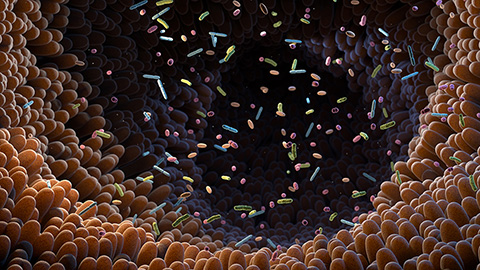

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.