Protein aggregation — defective or protective?

Protein aggregates may spell trouble in the brain, but could they help protect our skin? In a recent study in the Journal of Lipid Research, researchers demonstrate that apolipoprotein E, or ApoE, a protein linked to Alzheimer’s disease risk, can form aggregates with bacterial toxins to help clear infections.

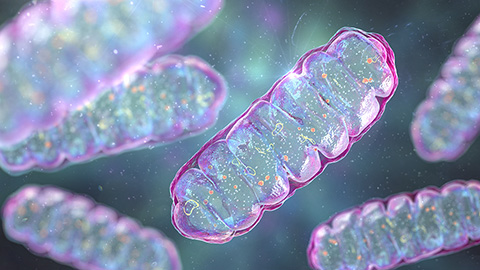

to Alzheimer’s disease can fight bacterial invaders, such as those illustrated here.

ApoE binds to lipids to regulate their metabolism and transport. Although the protein is also present in the intestines, lungs and skin, most ApoE studies focus on its role in the brain. This is because a particular variant of the protein is the greatest known genetic risk factor for late-onset sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Recently, however, Jitka Petrlova and researchers at the University of Lund found that ApoE made by skin cells can form large complexes, or aggregates, that help clear bacteria and toxins. This opens up a brand-new avenue for ApoE research as well as potential therapeutics.

Petrlova started studying ApoE as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, Davis, in John Voss’s lab, which studies Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s researchers generally regard protein aggregation as a pathological process that should be stopped at all costs; uncontrolled aggregation can create massive sticky plaques on the brain that impair function. Researchers believe certain ApoE variants increase the risk of developing Alzheimer’s by promoting formation of protein aggregates.

While studying ApoE structure, Petrlova noticed that parts of the protein looked like host-defense peptides, small molecules made by cells in the immune system that can help neutralize bacterial toxins. Suddenly, she understood why skin cells would make ApoE.

“It occurred to me how those two worlds could be connected,” Petrlova said. “ApoE could promote aggregation on the skin as a simple mechanism to grab the toxins and neutralize them to prevent our body from overreacting to them and going into septic shock.”

Now an associate professor in the dermatology division at the University of Lund, Petrlova continues to study whether ApoE’s ability to promote aggregation might be beneficial in the skin. Her lab has demonstrated that ApoE can bind and form complexes with lipopolysaccharide, a toxin on the surface of many bacteria, including E. coli, that can cause sepsis. The formation of these complexes helps cells kill the bacteria and clear the infection. So ApoE — a protein linked to developing dementia, the villain of the Alzheimer’s field — is actually a superhero on the skin.

Human bodies have made ApoE for millennia, and Petrlova believes that skin protection was the protein’s original purpose. “A thousand years ago we weren’t worried about getting dementia at age 70,” she said. “Our life-span was not more than 20 years. It was more important to us to beat bacteria, to survive in our hostile environment.

“To me, neurodegenerative diseases are the negative unintended consequences of overactive aggregating proteins. The first aim of the body is to kill bacteria. This must be ApoE’s true purpose.”

Future studies will focus on figuring out how well genetic variants of ApoE clear bacteria relative to each other. Because the ApoE4 variant increases Alzheimer’s risk by promoting aggregation, it likely will be better at clearing bacteria on the skin.

The findings could be translated readily to medical treatments. Petrlova envisions ApoE, or small pieces of it, being developed as a topical antimicrobial dressing that could be used to help prevent infections at surgical incision sites and to combat immune system weakening that occurs with aging.

“We are living longer. We are less active,” she said. “Older people often get lesions that do not heal properly, and this can affect their lifestyle. We need treatments to help people get back to their normal lives. So people can live better for longer.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Missing lipid shrinks heart and lowers exercise capacity

Researchers uncovered the essential role of PLAAT1 in maintaining heart cardiolipin, mitochondrial function and energy metabolism, linking this enzyme to exercise capacity and potential cardiovascular disease pathways.

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Defining JNKs: Targets for drug discovery

Roger Davis will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award in Biomedical Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.