Discovery could lead to more potent garlic, boosting flavor and bad breath

For centuries, people around the world have used garlic as a spice, natural remedy, and pest deterrent – but they didn’t know how powerful or pungent the heads of garlic were until they tasted them.

But what if farmers were able to grow garlic and know exactly how potent it would be? What if buyers could pick their garlic based on its might?

A team of Virginia Tech researchers recently discovered a new step in the metabolic process that produces the enzyme allicin, which leads to garlic’s delectable flavor and aroma, a finding that upends decades of previous scientific belief. Their work could boost the malodorous - yet delicious - characteristics that garlic-lovers the world over savor.

“This information changes the whole story about how garlic could be improved or we could make the compounds responsible of its unique flavor,” said Hannah Valentino, a College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Ph.D. candidate. “This could lead to a new strain of garlic that would produce more flavor.”

The discovery of this pathway opens the door for better control of production and more consistent crops, which would help farmers. Garlic could be sold as strong or weak, depending on consumer preferences.

The research was recently published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

When Valentino, an Institute for Critical Technology and Applied Science doctoral fellow, and her team set out to test the generally accepted biological process that creates allicin, they found it just didn’t happen.

That’s when the team of researchers set out to discover what was really happening in garlic.

As they peeled back the layers, they realized there was no fuel to power the previous accepted biological process that creates allicin.

“By using rational design, Hannah found a potential substrate,” said Pablo Sobrado, professor of biochemistry in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and a member of the research team. “This is significant because by finding the metabolic pathway and understanding how the enzyme actually works and its structure gives us a blueprint of how allicin is created during biosynthesis.”

Valentino and the team – which included undergraduate students – worked in the Sobrado Lab in the Fralin Life Sciences Institute directly with the substrates that comprise garlic, doing their work solely in vitro.

The researchers found that allicin, the component that gives garlic its smell and flavor, was produced by an entirely different biosynthetic process. Allyl-mercaptan reacts with flavin-containing monooxygenase, which then becomes allyl-sulfenic acid.

Importantly, the allicin levels can be tested, allowing farmers to know the strength of their crops without the need for genetic engineering. Greater flavor can simply be predicted, meaning powerful garlic could simply be bred or engineered.

“We have a basic understanding of the biosynthesis of allicin that it is involved in flavor and smell, but we also now understand an enzyme that we can try to modulate, or a modify, to increase or decrease the level of the flavor molecules based on these biological processes,” Sobrado said.

Because of their work, the future awaits for fields of garlic harsh enough to keep even the most terrifying vampires at bay.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

E-cigarettes drive irreversible lung damage via free radicals

E-cigarettes are often thought to be safer because they lack many of the carcinogens found in tobacco cigarettes. However, scientists recently found that exposure to e-cigarette vapor can cause severe, irreversible lung damage.

Using DNA barcodes to capture local biodiversity

Undergraduate at the University of California, Santa Barbara, leads citizen science initiative to engage the public in DNA barcoding to catalog local biodiversity, fostering community involvement in science.

Targeting Toxoplasma parasites and their protein accomplices

Researchers identify that a Toxoplasma gondii enzyme drives parasite's survival. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Scavenger protein receptor aids the transport of lipoproteins

Scientists elucidated how two major splice variants of scavenger receptors affect cellular localization in endothelial cells. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

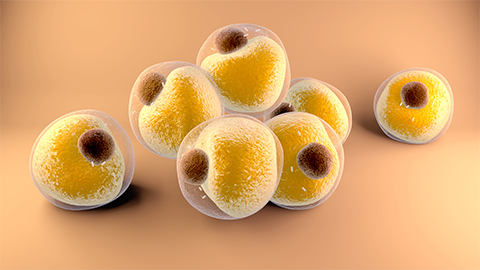

Fat cells are a culprit in osteoporosis

Scientists reveal that lipid transfer from bone marrow adipocytes to osteoblasts impairs bone formation by downregulating osteogenic proteins and inducing ferroptosis. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.