Science of 'Seinfeld'

It’s been 31 years since a groundbreaking show about nothing first hit the air and…yada yada yada. What better time to revisit some memorable moments from “Seinfeld” that left viewers shouting, “Get out!”, and see what science has to say about the situation.

I was a biology graduate student when “Seinfeld” first hit the air. The show not only provided a welcome reprieve from a tough day in the laboratory, but also fueled fun debates among us students as to whether the inane scenarios were plausible. Thirty years on, these debates still swim in my head, better informed by the latest science relevant to them.

Can men grow breasts big enough to need ‘the bro’?

On season 6, episode 18 (S6:E18), it was revealed that George’s father, Frank, had something he wanted to get off his chest but couldn’t: man boobs. After witnessing Frank’s condition, Kramer was inspired to make “the bro,” or “mansiere,” to help give Frank and his buddies support.

The development of enlarged breasts in men is nothing new: It is a rather common medical condition called gynecomastia. Gynecomastia can arise when the body makes less testosterone relative to estrogen. These fluctuations in sex hormones can happen as a newborn develops, during puberty or as a result of aging. In the young, the situation usually resolves on its own as hormones balance out.

Certain medications, illegal drugs and alcohol can produce gynecomastia as well. Men with this condition can opt for breast reduction surgery or wear a compression vest. Medications that reduce the effect of estrogen can also help.

Can someone die from licking envelopes?

In the season 7 finale, George and Susan were finally tying the knot and George’s wallet was taking a beating. When George was presented with the option to save a few bucks by purchasing old wedding invitations, he leaped at the opportunity. As she licked the 200 envelopes, Susan became dizzy and, in a shocking twist, died at the hospital. The doctor stated that they “found traces of a certain toxic adhesive commonly found in very low-priced envelopes.”

Another outlandish plot line, or could this really happen? According to “How It Works,” envelope glue is made from gum arabic, which is a product of the hardened sap from acacia trees. It is a nontoxic substance often used in candy to bind ingredients together.

Others state that dextrin, an edible carbohydrate produced from corn or potato starch, is used to make the adhesive. Most importantly, as far as I can tell, there is not a single report of someone dying from licking envelope glue. If you’re still anxious about potential toxins in the adhesive, or simply don’t like the taste, moisten the glue strip with a damp sponge instead of your tongue.

The government has been experimenting with pigmen

In S5:E5, Kramer wanders into the wrong hospital room and makes a disturbing discovery – a pigman: half man, half pig. Kramer is further convinced of the existence of pigman when the next day’s newspaper reads, “Hospital receives grant to conduct DNA research.” In the end, we learn that the pigman was, of course, just a man who is about five feet, hairless, with a pink complexion.

Kramer might come across as a hipster doofus, but he’s not entirely wrong here. Scientists have indeed been working on pig-human hybrids, of sorts, for decades. Doctors have been using porcine heart valves to replace damaged ones in humans since the 1960s.

Since a pig’s internal organs are roughly the same size as our own, pigs are good candidate animals in which human organs for transplantation could be grown. In 2017, Dr. Jun Wu at the Salk Institute published the first report of human tissue being grown in a pig embryo. Much more careful research lies ahead, but the pioneering study supports the idea that human organs could be manufactured in a pig.

Why does Newman hate broccoli so much?

In S8:E8, Newman was challenged to eat broccoli but quickly gagged and demanded a honey mustard chaser to neutralize the taste.

Newman is what scientists call a “supertaster,” and he is not alone in hating broccoli. Approximately 25% of people are born with variations in genes like TAS2R38, which build taste bud receptors.

Taste buds bind to chemicals in food and signal the flavor to the brain. Many plants, including broccoli, evolved to produce bitter-tasting chemicals like thiourea to avoid being eaten.

Most humans don’t register these chemicals as intensely bitter, but supertasters do. Supertasters are literally born with a tongue that is unusually sensitive to the bitter chemicals found in cruciferous vegetables like broccoli, which tricks their brain into thinking that the food is poisonous.

Like a frightened turtle, why does it shrink?

A trip out to the Hamptons is usually a pleasant outing, but in S5:E21, Jerry’s girlfriend accidentally walks in on George as he’s changing out of his swimsuit. After catching a glimpse of his manhood, she says, “I’m really sorry.” George screams in self-defense, “Shrinkage! Shrinkage! I was in the pool!”

George wasn’t lying. Urologist Darius Paduch at Weill Cornell Medicine has stated that the penis can shrivel by about 50% in length and 20% to 30% in girth in cold temperatures.

The human body operates at an optimal temperature of 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit. When we get cold, blood is redirected to our vital areas, namely our chest and head to keep our heart and brain functionally properly. Consequently, this draws blood away from appendages like fingers, toes and, in males, the penis. When blood rushes away from the penis, it shrinks. The position of the testes is a reflex controlled by the cremaster muscle, which brings them closer to the body in colder temperatures to maintain the warmth needed for sperm production.

Why you shouldn’t stress a model

Everything in life is coming up roses after George has a chance encounter with a hand modeling agent in S5:E2. Thanks to avoiding manual labor his whole life, George’s hands are exquisitely smooth and creamy, delicate yet masculine.

Appreciating that his extraordinary hands are the ticket to a new life, George protects them by wearing oven mitts and warning his bickering parents that “Stress is very damaging to the epidermis!”

It is tempting to assume that George is simply making excuses to get his parents to stop arguing, but science supports his assertion. Stress causes all sorts of health issues in the body, and the skin — our largest organ — is no exception. The body responds to stress by releasing hormones like cortisol, which cause inflammation.

In the skin, cortisol increases the production of oils, which can cause breakouts and exacerbate skin conditions such as psoriasis or eczema. Stress hormones negatively impact the immune system and epidermal defenses, making the skin more susceptible to infection. Stress also causes some people to bite their nails, which could easily ruin a hand modeling gig.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

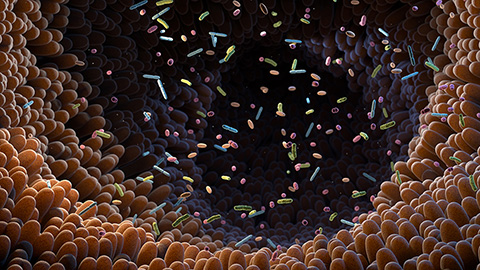

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

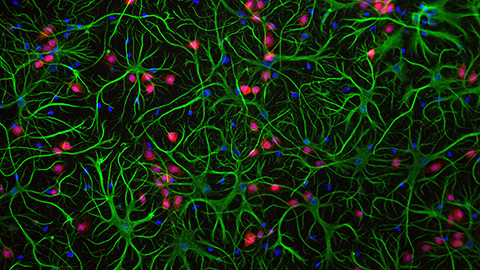

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.