What is the ACE2 receptor?

In the search for treatments for COVID-19, many researchers are focusing their attention on a specific protein that allows the virus to infect human cells. Called the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, or ACE2 “receptor,” the protein provides the entry point for the coronavirus to hook into and infect a wide range of human cells. Might this be central in how to treat this disease?

We are scientists with expertise in pharmacology, molecular biology and biochemistry, with a strong commitment to applying these skills to the discovery of novel therapies for human disease. In particular, all three authors have experience studying angiotensin signaling in various disease settings, a biochemical pathway that appears to be central in COVID-19. Here are some of the key issues to understand about why there’s so much focus on this protein.What is the ACE2 receptor?

ACE2 is a protein on the surface of many cell types. It is an enzyme that generates small proteins – by cutting up the larger protein angiotensinogen – that then go on to regulate functions in the cell.

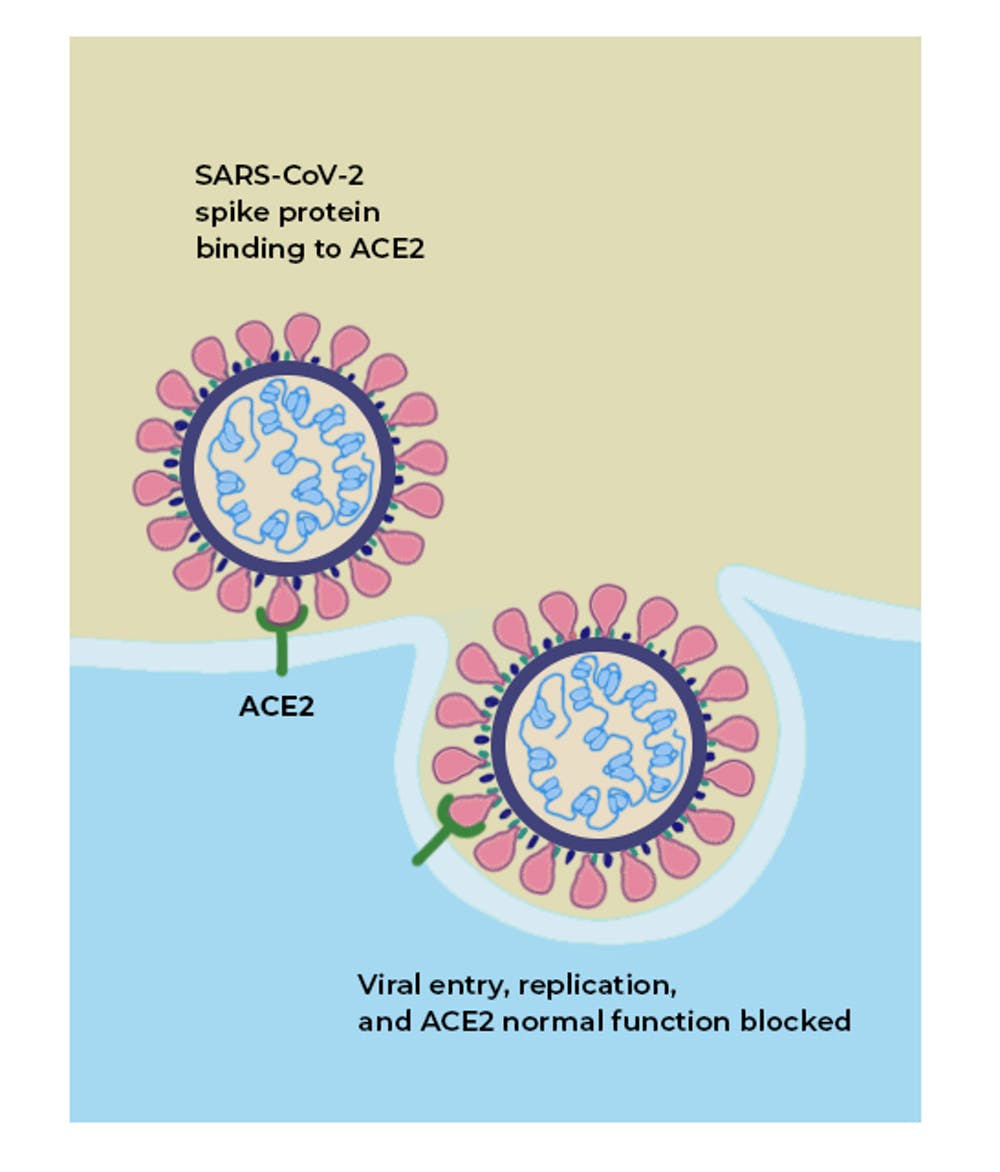

Using the spike-like protein on its surface, the SARS-CoV-2 virus binds to ACE2 – like a key being inserted into a lock – prior to entry and infection of cells. Hence, ACE2 acts as a cellular doorway – a receptor – for the virus that causes COVID-19.

Where in the body is it found?

ACE2 is present in many cell types and tissues including the lungs, heart, blood vessels, kidneys, liver and gastrointestinal tract. It is present in epithelial cells, which line certain tissues and create protective barriers.

The exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between the lungs and blood vessels occurs across this epithelial lining in the lung. ACE2 is present in epithelium in the nose, mouth and lungs. In the lungs, ACE2 is highly abundant on type 2 pneumocytes, an important cell type present in chambers within the lung called alveoli, where oxygen is absorbed and waste carbon dioxide is released.

What is the normal role ACE2 plays in the body?

ACE2 is a vital element in a biochemical pathway that is critical to regulating processes such as blood pressure, wound healing and inflammation, called the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) pathway.

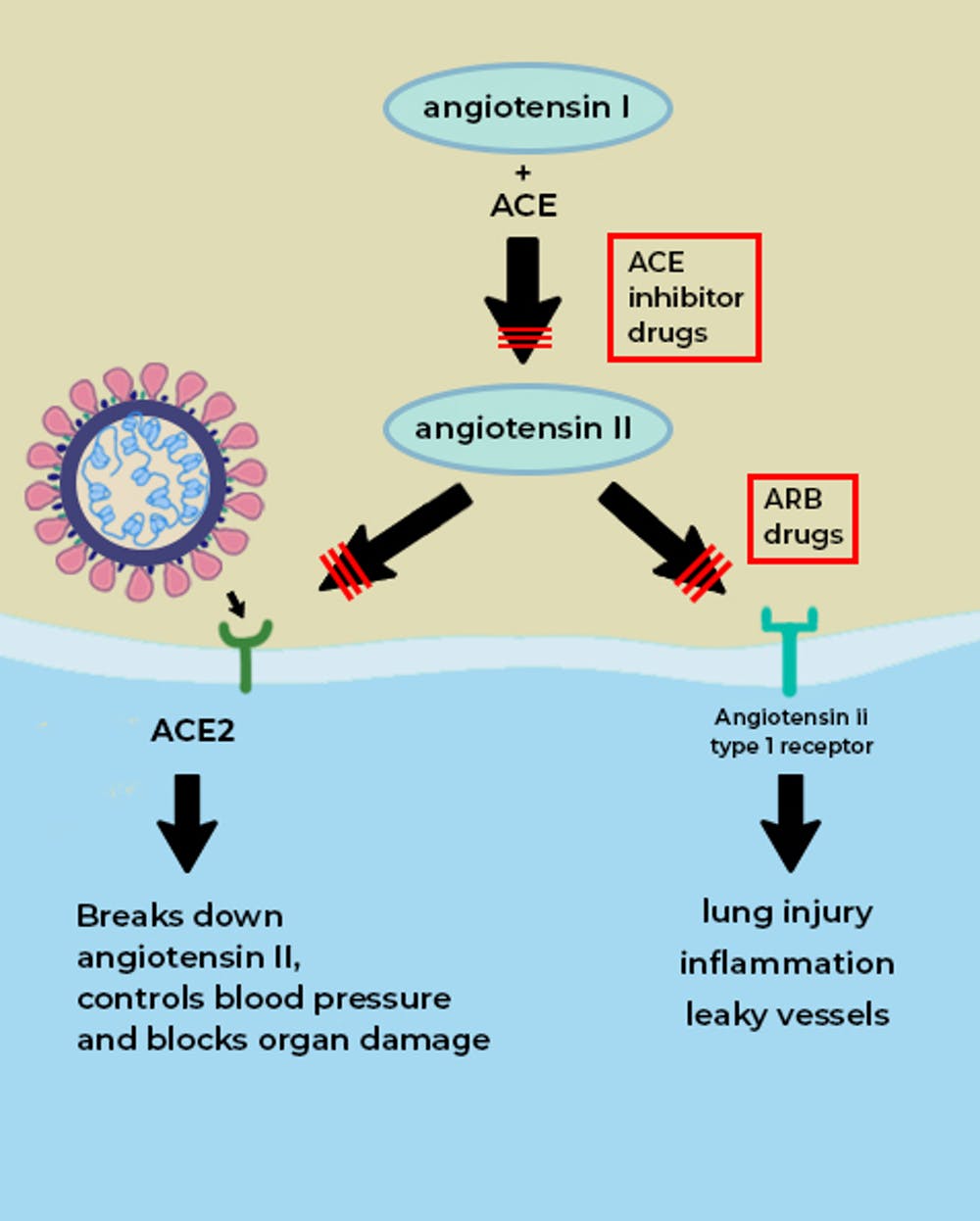

ACE2 helps modulate the many activities of a protein called angiotensin II (ANG II) that increases blood pressure and inflammation, increasing damage to blood vessel linings and various types of tissue injury. ACE2 converts ANG II to other molecules that counteract the effects of ANG II.

Of greatest relevance to COVID-19, ANG II can increase inflammation and the death of cells in the alveoli which are critical for bringing oxygen into the body; these harmful effects of ANG II are reduced by ACE2.

When the SARS-CoV-2 virus binds to ACE2, it prevents ACE2 from performing its normal function to regulate ANG II signaling. Thus, ACE2 action is “inhibited,” removing the brakes from ANG II signaling and making more ANG II available to injure tissues. This “decreased braking” likely contributes to injury, especially to the lungs and heart, in COVID-19 patients.

Does everyone have the same number of ACE2 on their cells?

No. ACE2 is present in all people but the quantity can vary among individuals and in different tissues and cells. Some evidence suggests that ACE2 may be higher in patients with hypertension, diabetes and coronary heart disease. Studies have found that a lack of ACE2 (in mice) is associated with severe tissue injury in the heart, lungs and other tissue types.

Does the quantity of receptors determine whether someone gets more or less sick?

This is unclear. The SARS-CoV-2 virus requires ACE2 to infect cells but the precise relationship between ACE2 levels, viral infectivity and severity of infection are not well understood.

Even so, aside from its ability to bind the SARS-CoV-2 virus, ACE2 has protective effects against tissue injury, by mitigating the pathological effects of ANG II.

When the amount of ACE2 is reduced because the virus is occupying the receptor, individuals may be more susceptible to severe illness from COVID-19. That is because enough ACE2 is available to facilitate viral entry but the decrease in available ACE2 contributes to more ANG II-mediated injury. In particular, reducing ACE2 will increase susceptibility to inflammation, cell death and organ failure, especially in the heart and the lung.

Which organs are most severely damaged by SARS-CoV-2?

The lungs are the primary site of injury by SARS-CoV-2 infection, which causes COVID-19. The virus reaches the lungs after entry in the nose or mouth.

ANG II drives lung injury. If there is a decrease in ACE2 activity (because the virus is binding to it), then ACE2 can’t break down the ANG II protein, which means there is more of it to cause inflammation and damage in the body.

The virus also impacts other tissues that express ACE2, including the heart, where damage and inflammation (myocarditis) can occur. The kidneys, liver and digestive tract can also be injured. Blood vessels may also be a site for damage.

In a recent research paper, we argued that a key factor that determines severity of damage in patients with COVID-19 is abnormally high ANG II activity.

What are ACE inhibitors? Are they a possible treatment or prophylactic for SARS-CoV-2?

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE, aka ACE1) is another protein, also found in tissues such as the lung and heart, where ACE2 is present. Drugs that inhibit the actions of ACE1 are called ACE inhibitors. Examples of these drugs are ramipril, lisinopril, and enalapril. These drugs block the actions of ACE1 but not ACE2. ACE1 drives the production of ANG II. In effect, ACE1 and ACE2 have a “yin-yang” relationship; ACE1 increases the amount of ANG II, whereas ACE2 reduces ANG II.

By inhibiting ACE1, ACE inhibitors reduce the levels of ANG II and its ability to increase blood pressure and tissue injury. ACE inhibitors are commonly prescribed for patients with hypertension, heart failure and kidney disease.

Another commonly prescribed class of drugs, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs, e.g., losartan, valsartan, etc.) have similar effects to ACE inhibitors and may also be useful in treating COVID-19.

Evidence for a protective effect of ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with COVID-19 was shown in recent work co-authored by one of us - Dr. Loomba.

No evidence exists to suggest prophylactic use of these drugs; we do not advise readers to take these drugs in the hopes that they will prevent COVID-19. We wish to emphasize that patients should only take these drugs as instructed by their health care provider.

New clinical trial tests ACE inhibitor against SARS-CoV-2

In collaboration with a multidisciplinary group of investigators, Dr. Loomba has initiated a multicenter (randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled) clinical trial to examine the efficacy of ramipril - an ACE inhibitor - compared to a placebo in reducing mortality, ICU admission or need for mechanical ventilation in patients with COVID-19.

[Get facts about coronavirus and the latest research. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Targeting Toxoplasma parasites and their protein accomplices

Researchers identify that a Toxoplasma gondii enzyme drives parasite's survival. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Scavenger protein receptor aids the transport of lipoproteins

Scientists elucidated how two major splice variants of scavenger receptors affect cellular localization in endothelial cells. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Fat cells are a culprit in osteoporosis

Scientists reveal that lipid transfer from bone marrow adipocytes to osteoblasts impairs bone formation by downregulating osteogenic proteins and inducing ferroptosis. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.

Exploring lipid metabolism: A journey through time and innovation

Recent lipid metabolism research has unveiled critical insights into lipid–protein interactions, offering potential therapeutic targets for metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases. Check out the latest in lipid science at the ASBMB annual meeting.

Melissa Moore to speak at ASBMB 2025

Richard Silverman and Melissa Moore are the featured speakers at the ASBMB annual meeting to be held April 12-15 in Chicago.