How is myelin made?

Myelin is the protective lipid sheath wrapped around a nerve. It functions as an insulator, akin to the protective coating on a wire, speeding up electrical transmission of signals along a neuron. Myelin also plays a role in maintaining the health of neurons. Myelin function is dysregulated in many neurological disorders, including multiple sclerosis.

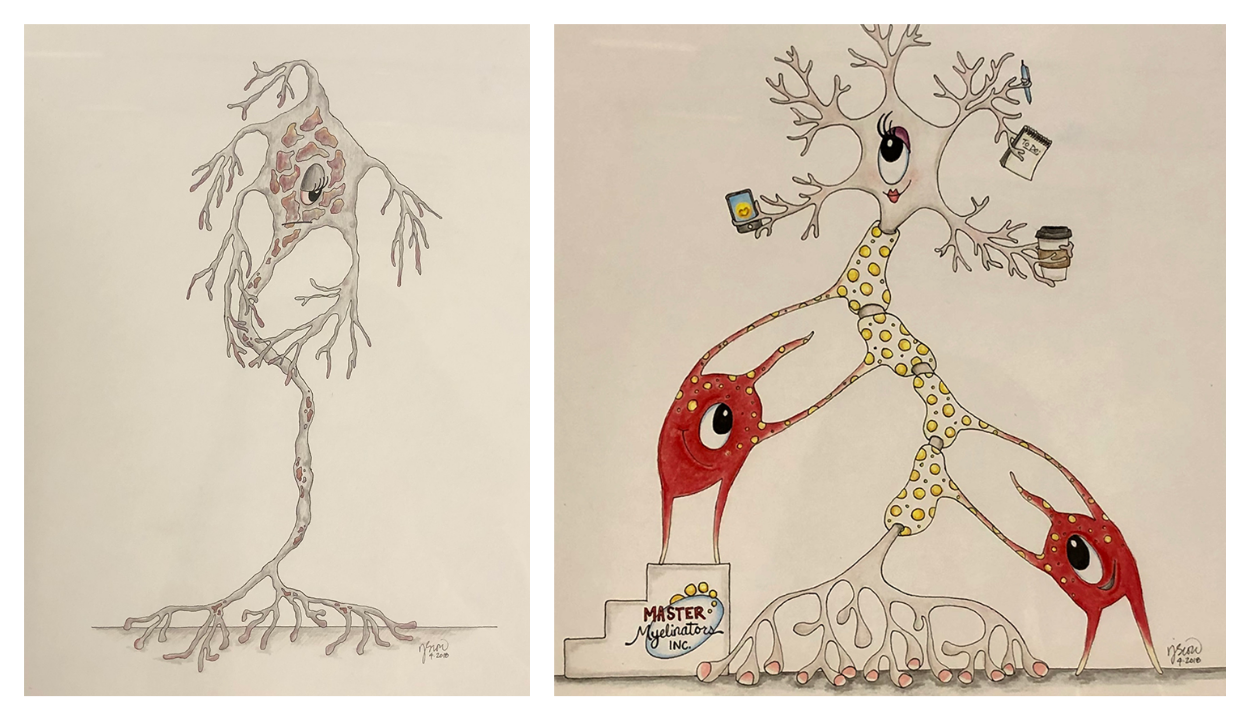

Oligodendrocytes are the myelin-producing cells of the central nervous system. The myelin sheath around a neuron is part of an oligodendrocyte’s plasma membrane, and a single oligodendrocyte can myelinate as many as 50 neurons. During myelination, an oligodendrocyte stretches out tubes of membrane in search of a neuron. When it finds one, it sends the necessary building materials down the tubes and, still operating from a distance, assembles a myelin sheet around the neuron: Composition, number of wraps and total coverage all matter. A myelinated neuron that loses its coating cannot transmit electrical signals properly, leading to loss of muscle control and other neurological problems.

The myelin sheath is mostly made of lipids, including sphingolipids, which are critical to myelin’s structure and function. The enzyme serine palymitoyltransferase, or SPT, produces the backbone of all sphingolipids, and the membrane-bound protein ORMDL monitors sphingolipid levels and regulates SPT activity. ORMDL’s activity must be precise: Too little sphingolipid production impedes myelination, and too much can be toxic.

Binks Wattenberg, a professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at Virginia Commonwealth University, studies membrane biogenesis and now focuses on lipid biogenesis. “I am very curious about how the cell knows when to make sphingolipid and when to stop,” Wattenberg said. “I think ORMDL might be the key to answering that question.”

Wattenberg’s next-door lab neighbor, Carmen Sato–Bigbee, a professor in the same department, studies myelination, with a focus on oligodendrocytes. The two joined forces to study the role of sphingolipid biosynthesis in myelination in developing brains, and reported their results in the Journal of Lipid Research.

To uncover the dynamics of sphingolipid content and synthesis during myelination, Wattenberg and Sato–Bigbee’s team worked with newborn rat brains, because peak myelination occurs directly after birth. Only one in five cells in the brain is an oligodendrocyte, so the team isolated these myelin-producing cells for their experiments.

The researchers found that a large portion of the sphingolipids present in oligodendrocytes during myelination have an atypically long backbone — an 18-carbon chain instead of a 16-carbon chain. “The 18-carbon chain backbone points to a change in lipid composition during myelination, which might explain the insulating properties of myelin,” Wattenberg said. “In future work, we want to look at the role of each type of sphingolipid in myelination.”

The study also found that SPT activity increases for the first few days of myelination and then begins to decrease. ORMDL activity is not measurable, but the team deduced that ORMDL isoform expression varies over time. These findings pave the way for future experiments.

“The control of sphingolipid biosynthesis is key to myelination, and understanding how this process works will enable us to alter it in future treatments,” Wattenberg said. “Our pie-in-the-sky goal is to understand sphingolipid biosynthesis so well that we can reprogram oligodendrocytes and reverse demyelination in degenerative myelination diseases like MS.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

When oncogenes collide in brain development

Researchers at University Medical Center Hamburg, found that elevated oncoprotein levels within the Wnt pathway can disrupt the brain cell extracellular matrix, suggesting a new role for LIN28A in brain development.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.