Chocolate’s secret ingredient

Whether baked as chips into a cookie, melted into a sweet warm drink or molded into the shape of a smiling bunny, chocolate is one of the world's most universally consumed foods.

Even the biggest chocolate lovers, though, might not recognize what this ancient food has in common with kimchi and kombucha: its flavors are due to fermentation. That familiar chocolate taste is thanks to tiny microorganisms that help transform chocolate's raw ingredients into the much-beloved rich, complex final product.

In labs from Peru to Belgium to Ivory Coast, self-proclaimed chocolate scientists like me are working to understand just how fermentation changes chocolate's flavor. Sometimes we create artificial fermentations in the lab. Other times we take cacao bean samples from real fermentations "in the wild." Often, we make our experimental batches into chocolate and ask a few lucky volunteers to taste it and tell us what flavors they detect.

After decades of running tests like this, researchers have solved many of the mysteries that govern cacao fermentation, including which microorganisms participate and how this step governs chocolate flavor and quality.

From seed pod to chocolate bar

The food you know as chocolate starts its life as the seeds of football-shaped pods of fruit growing directly from the trunk of the Theobroma cacao tree. It looks like something Dr. Seuss would have designed. But as long as 3,900 years ago the Olmecs of Central America had figured out a multi-step process to transform these giant seed pods into an edible treat.

First, workers crack the brightly colored fruit open and scoop out the seeds and pulp. The seeds, now called "beans," cure and drain over the course of three to 10 days before drying under the Sun. The dry beans are roasted, then crushed with sugar and sometimes dried milk until the mixture feels so smooth you can't distinguish the particles on your tongue. At this point, the chocolate is ready to be fashioned into bars, chips or confections.

It's during the curing stage that fermentation naturally occurs. Chocolate's complex flavor consists of hundreds of individual compounds, many of which are generated during fermentation. Fermentation is the process of improving the qualities of a food through the controlled activity of microbes, and it allows the bitter, otherwise tasteless cacao seeds to develop the rich flavors associated with chocolate.

Microorganisms at work

Cacao fermentation is a multi-step process. Any compound microorganisms produced along the way that changes the taste of the beans will also change the taste of the final chocolate.

The first fermentation step may be familiar to home brewers, because it involves yeasts – some of them the same yeasts that ferment beer and wine. Just like the yeast in your favorite brew, yeast in a cacao fermentation produces alcohol by digesting the sugary pulp that clings to the beans.

This process generates fruity-tasting molecules called esters and floral-tasting fusel alcohols. These compounds soak into the beans and are later present in the finished chocolate.

As the pulp breaks down, oxygen enters the fermenting mass and the yeast population declines as oxygen-loving bacteria take over. These bacteria are known as acetic acid bacteria because they convert the alcohol generated by the yeast into acetic acid.

The acid soaks into the beans, causing biochemical changes. The sprouting plant dies. Fats agglomerate. Some enzymes break proteins down into smaller peptides, which become very "chocolatey"-smelling during the subsequent roasting stage. Other enzymes break apart the antioxidant polyphenol molecules, for which chocolate has gained renown as a superfood. As a result, contrary to its reputation, most chocolate contains very few polyphenols, or even none at all.

All the reactions kicked off by acetic acid bacteria have a major impact on flavor. These acids encourage the degradation of heavily astringent, deep purple polyphenol molecules into milder-tasting, brown-colored chemicals called o-quinones. Here is where cacao beans turn from bitter-tasting to rich and nutty. This flavor transformation is accompanied by a color shift from reddish-purple to brown, and it is the reason the chocolate you're familiar with is brown and not purple.

Finally, as acid slowly evaporates and sugars are used up, other species – including filamentous fungi and spore-forming Bacillus bacteria – take over.

As vital as microbes are to the chocolate-making process, sometimes organisms can ruin a fermentation. An overgrowth of the spore-forming Bacillus bacteria is associated with compounds that lead to rancid, cheesy flavors.

Terroir of a place and its microbes

Cacao is a wild fermentation – farmers rely on natural microbes in the environment to create unique, local flavors. This phenomenon is known as "terroir": the characteristic flair imparted by a place. In the same way that grapes take on regional terroir, these wild microbes, combined with each farmer's particular process, confer terroir on beans fermented in each location.

Market demand for these fine, high-quality beans is growing. Makers of gourmet, small-batch chocolate hand-select beans based on their distinctive terroir in order to produce chocolate with an impressive range of flavor nuances.

If you've experienced chocolate only in the form of a bar you might grab near the grocery store checkout, you probably have little idea of the range and complexity that truly excellent chocolate can exhibit.

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation's newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

A bar from Akesson's Madagascar estate may be reminiscent of raspberries and apricots, while Canadian chocolate-maker Qantu's wild-fermented Peruvian bars taste like they've been soaked in Sauvignon Blanc. Yet in both cases, the bars contain nothing except cacao beans and some sugar.

This is the power of fermentation: to change, convert, transform. It takes the usual and make it unusual – thanks to the magic of microbes.![]()

Caitlin Clark, Ph.D. Candidate in Food Science, Colorado State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Cracking cancer’s code through functional connections

A machine learning–derived protein cofunction network is transforming how scientists understand and uncover relationships between proteins in cancer.

Gaze into the proteomics crystal ball

The 15th International Symposium on Proteomics in the Life Sciences symposium will be held August 17–21 in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

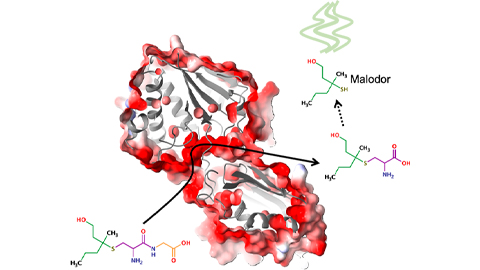

Bacterial enzyme catalyzes body odor compound formation

Researchers identify a skin-resident Staphylococcus hominis dipeptidase involved in creating sulfur-containing secretions. Read more about this recent Journal of Biological Chemistry paper.

Neurobiology of stress and substance use

MOSAIC scholar and proud Latino, Bryan Cruz of Scripps Research Institute studies the neurochemical origins of PTSD-related alcohol use using a multidisciplinary approach.

Pesticide disrupts neuronal potentiation

New research reveals how deltamethrin may disrupt brain development by altering the protein cargo of brain-derived extracellular vesicles. Read more about this recent Molecular & Cellular Proteomics article.

A look into the rice glycoproteome

Researchers mapped posttranslational modifications in Oryza sativa, revealing hundreds of alterations tied to key plant processes. Read more about this recent Molecular & Cellular Proteomics paper.