From the journals: JLR

A role for protein revealed in myelin disorders. Fat breakdown that’s larger than life, and then some. The full scope from one scoop. Read about papers on these topics recently published in the Journal of Lipid Research.

Role for protein revealed in myelin disorders

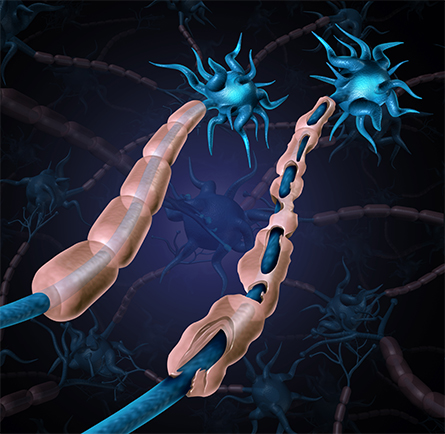

We know that the brain’s ability to control our every move is dependent on the many cells it consists of — neurons. Less known is how these neurons rapidly transmit signals that translate to our actions. Acting alone, a neuron might send a signal at just 4.5 miles an hour! Fortunately, they get a speed boost in the form of myelin.

as seen in multiple sclerosis and other chronic disorders.

Myelin is the lipid-rich membrane covering the length of most neurons and is an extension of other types of brain cells, namely oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells. This structure shields the electric signals running through our nerves, literally ramping up the speed to as fast as 120 miles per second. So, what can go wrong if neurons lose this on ramp?

In a process known as demyelination, neurons can be stripped of myelin, resulting in chronic disorders such as multiple sclerosis. Now, Yiran Liu and David Castano of the National University of Singapore and colleagues have discovered new roles for a protein, ABCA8b, in modulating neurons’ myelination.

ABCA8b exists mostly in mice brains and has a human counterpart, ABCA8. In their study published in the Journal of Lipid Research, the investigators genetically engineered mice with no ABCA8b in their brains. The absence of this protein reveals the importance of myelination. Their genetically engineered mice had abnormally shaped myelin and decreased speed of signals going through the nerves, and this manifested in irregular movement and even decreased amounts of the myelin producers — oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells. The observed abnormal movement stems from the brain region most damaged by demyelination, the cerebellum. With critical roles in movement coordination, cerebellum demyelination has grave consequences, such as MS.

Because the absence of ABCA8b translated to abnormal movements as seen in MS, the authors hope drug targets that increase this protein could lead to new therapies for people with myelin disorders.

Fat breakdown: Larger than life and then some

Obesity, connected with high levels of plasma lipids, is, among other things, a risk factor for the world’s No. 1 killer disease, cardiovascular disease. Many researchers are working to understand obesity, but it is challenging and complicated. Now, a team of scientists at Umeå University in Sweden has revealed another factor to consider: lipoprotein size.

Normally, the fat we eat is packaged into lipoproteins. Then, an enzyme called lipoprotein lipase, or LPL, breaks down the fat contained in these lipoproteins for energy needs of the body. However, in a recent paper in the Journal of Lipid Research, Oleg Kovrov, Fredrik Landfors and colleagues found that the most important determinant of LPL’s activity is the size of the lipoproteins.

Surprisingly, the team of investigators found that the levels of LPL’s regulators in the body had no significant effect on the lipase’s activity under the conditions used. Instead, they discovered that the larger lipoproteins correlated with higher LPL activity, probably due to a larger surface area in these proteins, which meant better returns for LPL’s work. This finding has implications for fat breakdown in humans, because the size of the lipoprotein particles varies from person to person and can vary throughout the day depending on food intake.

The full scope from one scoop

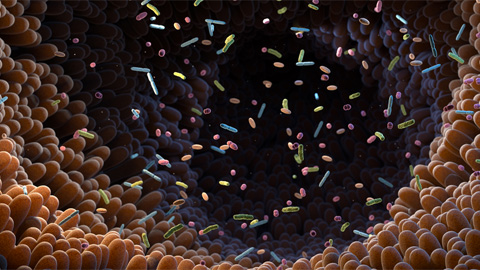

We all have to go — yet most of us give no further thought to our fecal matter after it’s flushed. What if some good can come from the go? A group of scientists at the Army Medical University in Chongqing, China, decided to find out.

In their study published in the Journal of Lipid Research Methods, Jiangang Zhang, Shuai Yang and colleagues devised a method that profiles fatty acids in fecal matter and tested this separation technique on fecal samples of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. This new method has promise for potential diagnostics.

That’s because existing methods for diagnosis often are invasive — especially in the case of cancer. Imagine going under the knife to determine if an organ is cancerous and even if it’s not, the patient is left with a scar.

The researchers’ method involves the use of LC–MS, which combines liquid chromatography, a technique that physically separates the fatty acid components in the fecal samples, with mass spectrometry analysis, which quantifies the fatty acid types found in the samples.

With a protocol that is high throughput, meaning large batches of samples can be processed, yet with no compromise of sample integrity, this new technique likely will translate widely in disease diagnostics.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Meet Donita Brady

Donita Brady is an associate professor of cancer biology and an associate editor of the Journal of Biological Chemistry, who studies metalloallostery in cancer.

Glyco get-together exploring health and disease

Meet the co-chairs of the 2025 ASBMB meeting on O-GlcNAcylation to be held July 10–13, 2025, in Durham, North Carolina. Learn about the latest in the field and meet families affected by diseases associated with this pathway.

Targeting toxins to treat whooping cough

Scientists find that liver protein inhibits of pertussis toxin, offering a potential new treatment for bacterial respiratory disease. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Elusive zebrafish enzyme in lipid secretion

Scientists discover that triacylglycerol synthesis enzyme drives lipoproteins secretion rather than lipid droplet storage. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Scientists identify pan-cancer biomarkers

Researchers analyze protein and RNA data across 13 cancer types to find similarities that could improve cancer staging, prognosis and treatment strategies. Read about this recent article published in Molecular & Cellular Proteomics.

New mass spectrometry tool accurately identifies bacteria

Scientists develop a software tool to categorize microbe species and antibiotic resistance markers to aid clinical and environmental research. Read about this recent article published in Molecular & Cellular Proteomics.