Identification of ceramide-1-phosphate transport proteins

Recently, investigators have identified the protein that carries the important sphingolipid ceramide-1-phosphate in humans. This finding helps us understand how C1P is transported inside cells to carry out its critical signaling functions for processes such as cell proliferation and migration.

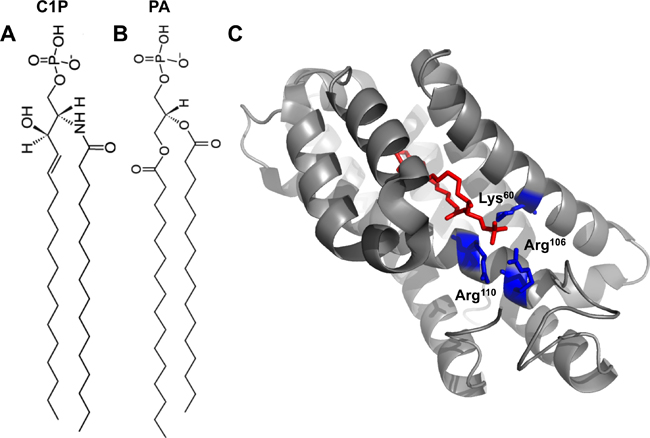

Sphingolipids play key roles in cellular signaling and membrane trafficking — with sphingosine, sphingosine-1-phosphate, ceramide and C1P acting as the main players (1).C1P is an anionic sphingolipid containing a phosphomonoester headgroup (see Figure 1A) and in mammalian cells is synthesized from ceramide by the enzyme ceramide kinase. CerK was discovered more than 20 years ago by a team that co-purified it with brain synaptic vesicles (2); to date, it remains the only kinase known in mammalian cells to convert ceramide to C1P.

In 2002, CerK was cloned and found to be expressed in the brain, heart, kidney, lung and hematopoietic cells (3). Since then, the many bioactive roles for C1P have been elucidated. These include macrophage migration, cell proliferation, stem cell mobilization and regulation of eicosanoid production (4, 5).

|

| Fig. 1A: 16:0-C1P. 1B: 16:0-PA. 1C: Crystal structure of CPTP in complex with 16:0-C1P (PDB ID: 4K84). Cationic residues (Lys60, Arg106 and Arg110) that bind the phosphate headgroup of C1P are shown in blue. The C1P acyl chains are ensheathed in the deep hydrophobic pocket beneath the surface cationic residues that interact with the phosphate headgroup. |

‘An exciting finding’

CerK is localized to the trans-Golgi network, where it generates C1P from ceramide. At the trans-Golgi network, C1P has been shown to activate the pro-inflammatory enzyme cytosolic phospholipase A2α, or cPLA2α (6). More recently, C1P has been shown to regulate other proteins (7, 8); however, the cellular mechanisms and localizations are not well understood. C1P may be transported via vesicular transport from the trans-Golgi network (9), but for the most part, how specifically C1P is disseminated from the trans-Golgi network to other cellular membranes, where it interacts with effector proteins, remained unknown until recently.

Last year, a multidisciplinary team reported in the journal Nature that it had identified a putative C1P transfer protein, or CPTP, in humans (10).

The team screened the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s human genome and identified a predicted transcript with 17 percent sequence identity with glycolipid transfer protein, or GLTP.

The authors demonstrated that the mRNA for this construct was found in most tissues and that the recombinant protein can transfer C1P selectively between phosphatidylcholine vesicles. This is an exciting finding for the lipid research community, as lipid-transport proteins for sterols, ceramide, glycolipids and glycerophospholipids have been studied intensely (11, 12, 13), and yet those for lipids such as C1P had remained unexplored.

Structural details for CPTP

The authors went on to solve the structure of CPTP bound to several lipids, including C1P, with varying acyl chains. The structure revealed an α-helical topology and a fold homologous to that of GLTP (see Fig. 1C).

CPTP has one surface enriched in cationic residues, which contains three amino acids (Lys60, Arg106 and Arg110) critical for binding to the C1P phosphate headgroup. Mutation of these residues greatly diminished the ability of CPTP to transport C1P.

Below this surface cationic patch lies a portal to a deep hydrophobic cavity that can accommodate both acyl chains of the C1P molecule. This hydrophobic pocket is highly flexible and can expand to accommodate the sphingosine and acyl chains of 16:0- and 18:1-C1P. The authors demonstrate that this pocket wasn’t as adaptable to accommodating longer acyl chains (such as lignoceryl) and thus propose that CPTP may serve to transfer 16:0- and 18:1-C1P selectively in cells.

The structure of CPTP with phosphatidic acid bound (see Figure 1B) also was solved to investigate why a different anionic phosphomonoester was not transferred efficiently by CPTP.

Phosphatidic acid interacts with the same residues as the C1P headgroup but with a slightly different H-bonding arrangement. Additionally, the lack of the acyl amide moiety on phosphatidic acid precluded the interaction with residues in CPTP that bound the acyl amide of C1P. Thus, phosphatidic acid had altered headgroup and acyl chain positions compared with C1P, which was determined to loosen the phosphatidic acid binding. This distorted orientation likely dampens transfer of phosphatidic acid.

Cellular studies of C1P transport

In cells, CPTP visualized by antibody or enhanced green fluorescent protein tag was found in the cytosol but also associated with the trans-Golgi network, endosomes, nuclei and plasma membrane. Thus, the authors propose a C1P-sensing role for CPTP at the trans-Golgi network during CERK signaling.

Silencing of CPTP in human cells resulted in elevated cellular 16:0-C1P and 24:1-C1P as well as fragmented Golgi cisternal stacks. Subcellular fractionation showed that C1P levels were increased in the trans-Golgi network, endosomal and nuclear fractions but were decreased in the plasma membrane. CPTP overexpression could rescue these effects.

CPTP involvement in C1P effector cPLA2α activity was also assessed. When CPTP was silenced, arachidonic acid levels increased, consistent with C1P accumulation and therefore increased cPLA2α activation at the trans-Golgi network. Metabolites of cyclooxygenase, lipoxygenase and CYP450 pathways also were increased. Conversely, eicosanoid levels decreased upon overexpression of wild-type CPTP but not dominant negative mutations.

The authors suggest that CPTP acts as a C1P sensor, transferring C1P from the trans-Golgi network to the plasma membrane as levels increase such that C1P does not build up in the trans-Golgi network. This would also allow for fine-tuning of cPLA2α activity and the ability to regulate arachidonic acid generation. CPTP depletion also had effects on other sphingolipids, namely decreased cellular levels of sphingosine, sphingosine-1-phosphate and sphingomyelin.

While metabolism of C1P back to another sphingolipid (ceramide or S1P) is still a controversial subject, this new study suggests that perhaps deacylation of C1P may occur as silencing of CPTP reduces cellular levels of S1P and sphingosine.

CPTP does not appear to be limited to mammalian cells. A CPTP was found in Arabidopsis (14). In that model, cell death 11 mutant, or ACD11, is able to transfer C1P or phyto-C1P, the major component of plant cells.

The structure of ACD11, like that of CPTP, revealed a surface cationic patch for C1P headgroup recognition and a hydrophobic pocket that can accommodate the lipid chains. In null ACD11 cells, normally low levels of phyto-C1P greatly rise, leading to an increase in phyto-ceramides and programmed cell death.

What’s to come?

Many questions about C1P-mediated signaling and cellular transport remain unanswered.

For instance, which lipids CPTP binds at the trans-Golgi network and plasma membrane is unknown, and how specifically it transports C1P from the Golgi to the plasma membrane is not understood. However, these represent exciting questions for future studies.

C1P also has unique biophysical properties that may play roles in its signaling and transport (15). In closing, these new studies identifying the existence of CPTPs will generate much excitement toward further unraveling the mechanism and role of C1P signaling in normal and pathological processes.

References

- 1. ↵ Hannun, Y.A. and Obeid, L.M. J. Biol. Chem.32, 27855 – 27862 (2011).

- 2. ↵ Bajjalieh, S.M. et al. J. Biol. Chem.24, 14354 – 14360 (1989).

- 3. ↵ Sugiura, M. et al. J. Biol. Chem.26, 23294 – 23300 (2002).

- 4. ↵ Hoeferlin, L.A. et al. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol.215, 153 – 166 (2013).

- 5. ↵ Gomez-Muñoz, A. et al. Biochim. Biophys. Acta.1831, 1060-1066 (2013).

- 6. ↵ Lamour, L. et al. J. Biol. Chem.39, 26897 – 26907 (2009).

- 7. ↵ Lamour, L. et al. J. Biol. Chem.50, 42808 – 42817 (2011).

- 8. ↵ Hankins, J. et al. J. Biol. Chem.27, 19726 – 19738 (2013).

- 9. ↵ Boath, A. et al. J. Biol. Chem.13, 8517 – 8526 (2008).

- 10. ↵ Simanshu, D.K. et al. Nature500, 463 – 467 (2013).

- 11. ↵ Schaaf, G. et al. Mol. Cell., 29, 191 – 206 (2008).

- 12. ↵ Villasmil, M.L. et al. Biochem. Soc. Trans.40, 469 – 473 (2012).

- 13. ↵ Prinz, W.A. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.15, 79 (2014).

- 14. ↵ Simanshu, D.K. et al. Cell Reports6, 388 – 399 (2014).

- 15. ↵ Kooijman, E.E. et al. Biophys. J.94, 4320 – 4330 (2008).

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Targeting Toxoplasma parasites and their protein accomplices

Researchers identify that a Toxoplasma gondii enzyme drives parasite's survival. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Scavenger protein receptor aids the transport of lipoproteins

Scientists elucidated how two major splice variants of scavenger receptors affect cellular localization in endothelial cells. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Fat cells are a culprit in osteoporosis

Scientists reveal that lipid transfer from bone marrow adipocytes to osteoblasts impairs bone formation by downregulating osteogenic proteins and inducing ferroptosis. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.

Exploring lipid metabolism: A journey through time and innovation

Recent lipid metabolism research has unveiled critical insights into lipid–protein interactions, offering potential therapeutic targets for metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases. Check out the latest in lipid science at the ASBMB annual meeting.

Melissa Moore to speak at ASBMB 2025

Richard Silverman and Melissa Moore are the featured speakers at the ASBMB annual meeting to be held April 12-15 in Chicago.