Progesterone from an unexpected source may affect miscarriage risk

About 20% of confirmed pregnancies end in miscarriage, most often in the first trimester, for reasons ranging from infection to chromosomal abnormality. But some women have recurrent miscarriages, a painful process that points to underlying issues. Clinical studies have been uneven, but some evidence shows that for women with a history of recurrent miscarriage, taking progesterone early in a pregnancy might moderately improve these women’s chances of carrying a pregnancy to term.

A recent study in the Journal of Lipid Research sheds light on a new facet of progesterone signaling between maternal and embryonic tissue. The work hints at a preliminary link between disruptions to this signaling and recurrent miscarriage.

Progesterone plays an important role in embedding the placenta into the endometrium, the lining of the uterus. The hormone is key for thickening the endometrium, reorganizing blood flow to supply the uterus with oxygen and nutrients, and suppressing the maternal immune system.

Progesterone is made in the ovary as a normal part of the menstrual cycle, and at first, this continues after fertilization. About six weeks into pregnancy, the placenta takes over making progesterone, a critical handoff. (The placenta also makes other hormones, including human chorionic gonadotropin, which is detected in a pregnancy test.) Placental progesterone comes mostly from surface tissue organized into fingerlike projections that integrate into the endometrium and absorb nutrients. Some cells leave those projections and migrate into the endometrium, where they help to direct the reorganization of arteries.

Using cells from terminated pregnancies, Austrian researchers led by Sigrid Vondra and supervised by Jürgen Pollheimer and Clemens Röhrl compared the cells that stay on the placenta’s surface with those that migrate into the endometrium. They discovered that the enzymes responsible for progesterone production differ between those two cell types early in pregnancy.

As a steroid hormone, progesterone is derived from cholesterol. Although the overall production of progesterone appears to be about the same in migratory and surface cells, migratory cells accumulate more cholesterol and express more of a key enzyme for converting cholesterol to progesterone. Among women who have had recurrent miscarriages, that enzyme is lower in migratory cells from the placenta than it is among women with healthy pregnancies. In contrast, levels of the enzyme don’t differ between healthy and miscarried pregnancies in cells from the surface of the placenta.

The team’s findings suggest that production of progesterone by the migratory cells may have a specific and necessary role in early pregnancy and that disruption to that process could be linked to miscarriage.

“If we can identify the exact mechanisms and cells that are affected,” Vondra said, “that would lead us one step closer to understanding the big picture of what causes recurrent miscarriages and possibly to being able to intervene and allow these women to have successful pregnancies.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

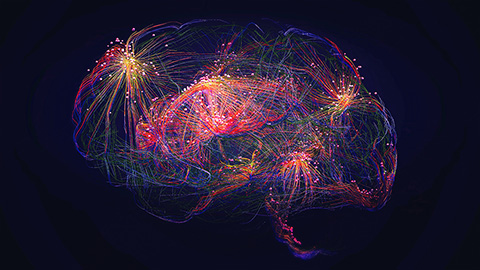

When oncogenes collide in brain development

Researchers at University Medical Center Hamburg, found that elevated oncoprotein levels within the Wnt pathway can disrupt the brain cell extracellular matrix, suggesting a new role for LIN28A in brain development.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

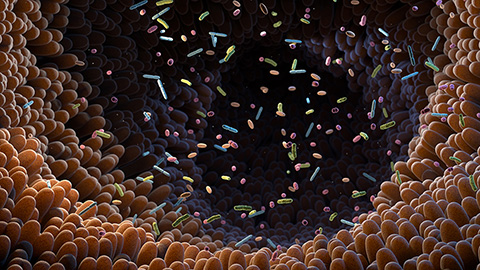

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.