Quantifying bacteria-borne bile

that may cause metabolic disease

Beyond breaking down food, the steroid bile acids produced both by our livers and by our intestinal inhabitants have a range of functions, from helping absorb lipids and fat-soluble vitamins to acting as signaling molecules for myriad pathways.

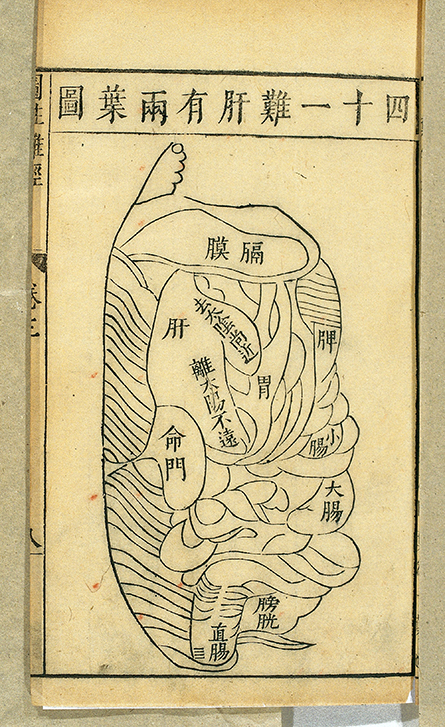

for the production of primary bile acids.

When gut microbes use amino acids to conjugate metabolites or primary bile acids created by the liver, secondary bile acids are formed. These secondary acids are linked to an increased risk of metabolic diseases, but their physiochemical properties make it difficult to puzzle out which bile acids are being produced by which gut bacteria. To rectify this, researchers in Stanley L. Hazen’s laboratory at the Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Microbiome and Human Health have developed a new stable isotope dilution liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method to quantify bile acids in mice and humans. They described their method in the Journal of Lipid Research.

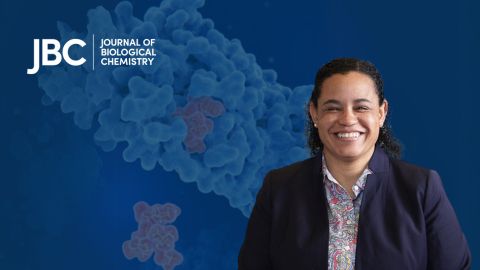

Ima Nemet is a senior scientist in Hazen’s lab and the corresponding author on the paper. “We know that so many bile acids have been known and studied for a long time, but we wanted to have some very robust methods that can be very easily used for large clinical studies,” Nemet said. “When we run these large cohorts, we use multiple instruments that are sometimes even from different vendors. So we wanted to have something that’s ‘clickable’ on all different types of machines.”

Eating foods containing high amounts of choline, notably red meat, spurs gut bacteria to produce the bile acid trimethylamine N-oxide, or TMAO, Hazen and colleagues reported in 2018. TMAO can cause plaque to accumulate in arteries and is a predictor of heart attacks. They reported in 2015 that TMAO derived from dietary sources of choline was elevated in cases of chronic kidney diseases.

To validate their new analytical method, a bile acid panel, the researchers examined circulating levels of more than 50 primary and secondary bile acids in serum and fecal samples from mice and humans. They used the panel to identify a handful of circulating bile acids associated with diabetes in samples obtained from a study of people with Type 2 diabetes.

Nemet was intrigued to find that bacteria played a role in regulating the production of a number of primary bile acids that were thought to be produced exclusively by the liver.

“The circulating levels of three primary bile acids are completely dependent on microbial activity,” she said. “That’s really interesting for me, because usually people say primary bile acids are host-derived, but … if we put humans or mice on antibiotics, these levels go down. That means the majority of these bile acids are coming from microbial contribution, even though we’re calling them primary.”

Nemet and Hazen plan to use the bile panel to test samples from larger clinical studies before homing in on the specific mechanisms by which bile acids increase the risk of Type 2 diabetes, which potentially could be disrupted by small-molecule drugs.

“This is our start in looking into the contribution of bile acids in developing metabolic diseases,” Nemet said. “There are now a plethora of experiments where we can now look and see whether these metabolites are just associations or whether they are driving Type 2 diabetes.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Meet Donita Brady

Donita Brady is an associate professor of cancer biology and an associate editor of the Journal of Biological Chemistry, who studies metalloallostery in cancer.

Glyco get-together exploring health and disease

Meet the co-chairs of the 2025 ASBMB meeting on O-GlcNAcylation to be held July 10–13, 2025, in Durham, North Carolina. Learn about the latest in the field and meet families affected by diseases associated with this pathway.

Targeting toxins to treat whooping cough

Scientists find that liver protein inhibits of pertussis toxin, offering a potential new treatment for bacterial respiratory disease. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Elusive zebrafish enzyme in lipid secretion

Scientists discover that triacylglycerol synthesis enzyme drives lipoproteins secretion rather than lipid droplet storage. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Scientists identify pan-cancer biomarkers

Researchers analyze protein and RNA data across 13 cancer types to find similarities that could improve cancer staging, prognosis and treatment strategies. Read about this recent article published in Molecular & Cellular Proteomics.

New mass spectrometry tool accurately identifies bacteria

Scientists develop a software tool to categorize microbe species and antibiotic resistance markers to aid clinical and environmental research. Read about this recent article published in Molecular & Cellular Proteomics.