JLR: New insights into treating amoebic keratitis

The human body provides a hospitable environment for many micro-organisms that are essential to our survival. At the same time, it also attracts a host of parasites that, if not treated properly or eradicated, can be extremely harmful to our health. One such class of parasite is the infective amoeba, which causes rare and sometimes fatal diseases in humans. The Acanthamoeba species, found worldwide, mostly in water and soil, causes amoebic keratitis, or AK — an eye infection of the cornea that can result in permanent blindness. In the USA, 85 percent of AK cases occur in soft contact lens users. Although AK is potentially life-threatening, its treatment is not yet promising, owing to drug resistance and the absence of species-specific drugs. Hence, we need to identify specific drug targets to better fight these parasites.

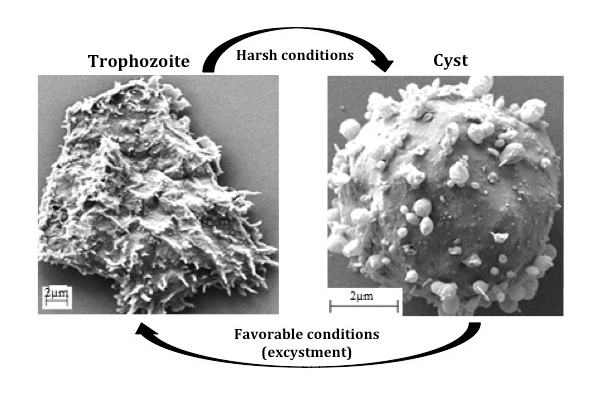

Designing species-specific drugs requires an understanding of the unique evolutionary differences among species, especially with respect to biochemical pathways responsible for the survival of the parasite within the host. The Acanthamoeba life cycle has two stages — cyst and trophozoite. The trophozoite is the active form that infects humans, while the cyst is the dormant form that can survive harsh conditions such as stress and lack of nutrients. When conditions become favorable, the cyst transforms to a trophozoite via a process called excystment. Both forms can enter the human body through wounds, nostrils or contact with water.

Electron micrographs show the two stages in the life cycle of Acanthamoeba castellani. Courtesy of the W. David NES labORATORY

Electron micrographs show the two stages in the life cycle of Acanthamoeba castellani. Courtesy of the W. David NES labORATORY

Certain metabolic pathways cause the Acanthamoeba to cycle between stages and help the infective trophozoites survive and proliferate in humans. Thus, targeting these specific pathways could prove to be an efficient strategy to treat Acanthamoeba infections. W. David Nes and his group at Texas Tech University have investigated such pathways and reported sterol C24-methyltransferases, or SMTs, synthesized only in amoebae, as novel druggable targets. Their findings were published in the Journal of Lipid Research.

Sterols are amphipathic molecules that, by virtue of their lipid-based properties, act as membrane inserts to control overall growth and development. Ergosterol biosynthesis has been established as essential for the survival of many amoebae in humans, and SMTs are critical enzymes in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway. SMTs catalyze a crucial step in the ergosterol pathway that maintains trophozoite growth. Interestingly, SMTs are absent in humans. Thus, the researchers found that inhibiting these enzymes with transition-state analogs that blocked the catalytic site on the enzyme, or with suicide substrates that irreversibly bound covalently to the enzyme, stopped the growth of trophozoites but had no effect on normal cholesterol biosynthesis in human cells. So this approach could treat specifically Acanthamoeba infections without harming us. This is the highlight of Nes’ published work.

The work has been quite challenging, especially because differences in sterol biochemistry and life-cycle events among amoeba species make it hard to identify common drug targets. Moreover, Nes’ group required an extensive collaboration to integrate a multidisciplinary approach so as to provide “the most effective drugs, which would escape mechanisms that otherwise could compromise their therapeutic longevity,” Nes said.

Having used keratitis-causing Acanthamoeba castellanii as the model system in their published study, Nes and his group now want to test their hypothesis in mouse models. They also plan to extend their inhibitor studies to Naegleria fowlerii, a “brain-eating amoeba” that can cross the blood-brain barrier and destroy brain tissue, resulting in a disease called primary amoebic meningoencephalitis, or PAM. Further down the road, they hope to develop high-throughput screening techniques to repurpose existing drugs as novel SMT catalysis inhibitors to cure amoebic infections.

Isha Dey is a Ph.D. candidate at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science.

Isha Dey is a Ph.D. candidate at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science.Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Defining JNKs: Targets for drug discovery

Roger Davis will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award in Biomedical Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Building better tools to decipher the lipidome

Chemical engineer–turned–biophysicist Matthew Mitsche uses curiosity, coding and creativity to tackle lipid biology, uncovering PNPLA3’s role in fatty liver disease and advancing mass spectrometry tools for studying complex lipid systems.

Redefining lipid biology from droplets to ferroptosis

James Olzmann will receive the ASBMB Avanti Award in Lipids at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Life in four dimensions: When biology outpaces the brain

Nobel laureate Eric Betzig will discuss his research on information transfer in biology from proteins to organisms at the 2026 ASBMB Annual Meeting.

Fasting, fat and the molecular switches that keep us alive

Nutritional biochemist and JLR AE Sander Kersten has spent decades uncovering how the body adapts to fasting. His discoveries on lipid metabolism and gene regulation reveal how our ancient survival mechanisms may hold keys to modern metabolic health.