JBC: Another role for c-Myc, one of cancer’s biggest players

Cancers involve a diverse range of genes and proteins that aid in their formation, progression and maintenance. One gene that has been implicated in many cancers is c-Myc. One cancer, a common liver cancer in children, didn’t appear to involve c-Myc. But now, in a recent article selected as one of the Editors’ Picks in in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, a team led by Edward Prochownik of the University of Pittsburgh has shown that hepatoblastomas are no different from most other cancers: Tumor progression requires c-Myc.

c-Myc’s absence in the liver impairs tumor growth but not initiation.IMAGE PROVIDED BY EDWARD PROCHOWNIKThe c-Myc gene encodes a transcription factor, which is a protein that binds to DNA and promotes the expression of particular genes. When c-Myc is overexpressed in cancers, it effectively signals to turn on other genes at levels higher than normal. The products of these genes then can promote cancer development and progression.

c-Myc’s absence in the liver impairs tumor growth but not initiation.IMAGE PROVIDED BY EDWARD PROCHOWNIKThe c-Myc gene encodes a transcription factor, which is a protein that binds to DNA and promotes the expression of particular genes. When c-Myc is overexpressed in cancers, it effectively signals to turn on other genes at levels higher than normal. The products of these genes then can promote cancer development and progression.

Hepatoblastoma is the most common pediatric liver cancer. It often is diagnosed in children under the age of 3 and occurs with higher incidence in low-birthweight infants. Survival rates are greater than 80 percent if the tumor is removed completely with surgery but drop to as low as 20 percent if the tumor spreads beyond the liver.

On the surface, c-Myc generally doesn’t appear to be involved in the formation of hepatoblastoma, although it has been seen at high levels in some tumors. Instead, hepatoblastoma is characterized by mutations in two key proteins: beta-catenin and yes-associated protein, abbreviated YAP. “In our work, we asked whether c-Myc was required for beta-catenin and YAP to induce hepatoblastomas in mice,” explains Prochownik.

The investigators asked if the two proteins lead to cancer by themselves or if they also need c-Myc. They used mice genetically engineered to lack the c-Myc gene in their livers and then used beta-catenin and YAP to induce hepatoblastoma formation. They observed that the mice lacking c-Myc in their livers survived much longer than mice with intact c-Myc.

The researchers used metabolic and molecular profiling to understand why the mice without c-Myc survived longer. Through techniques including RNA sequencing and mitochondrial analysis, they observed a role for c-Myc in supporting tumor growth. “The apparent role for c-Myc in supporting tumor growth was its ability to maximize certain crucial metabolic processes, such as protein synthesis and glucose uptake,” says Prochownik. There were more cellular building blocks that made increased growth and cancer progression possible.

The work of Prochownik and colleagues indicates that c-Myc is involved in tumor progression but not initiation. Given c-Myc’s involvement in a number of cancers, why is this news? “Our findings indicate that even tumors which do not superficially appear to involve c-Myc deregulation, such as hepatoblastomas, are nevertheless highly dependent on it,” explains Prochownik.

This was somewhat surprising, as recent work from the same laboratory has shown that c-Myc is not required for the long-term replacement and maintenance of normal noncancerous liver cells. Prochownik’s group believes that this disparity is due to the nature of cancerous cells. c-Myc is largely dispensable in normal cells that have relatively slow and highly controlled growth. However, in cancer cells that undergo rapid division and metabolism, c-Myc is required. c-Myc’s role may be to allow cells to utilize nutrients and cellular precursors to permit the type of rapid proliferation that seldom would occur under normal circumstances.

c-Myc is possibly the most frequently deregulated protein in human cancer, making it a good target for therapeutics. The work of Prochownik and colleagues suggests that targeting c-Myc may prove useful even for cancers that don’t appear to be initiated by c-Myc deregulation, such as hepatoblastoma. “Our data suggest that pharmacologic approaches specifically targeting c-Myc or some of the pathways it regulates might be viable targets for novel therapeutic interventions,” says Prochownik.

Maybe in the future, one of cancer’s most active players can be stopped.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

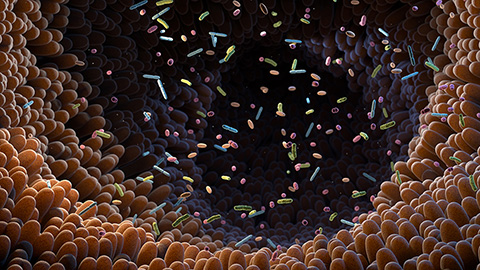

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

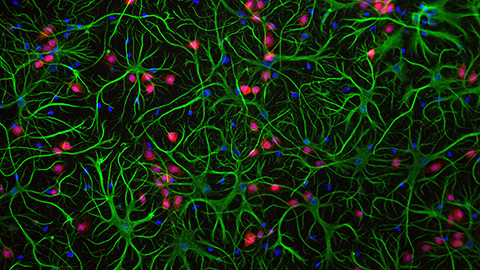

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.