‘Traffic jam’ discovery in yeast could lead to new disease treatments

Ball State University biology students have accomplished something few students get the chance to do in their college careers — make a crucial discovery that could lead to new treatments for diseases, including diabetes and cancer.

Eric (VJ) Rubenstein, associate professor of biology, and some of his current and former students have identified two molecules they compare to tow trucks that help keep cells healthy.

Their research was published in the November issue of the Journal of Biological Chemistry. The paper is a culmination of dozens of experiments performed by Ball State students in Rubenstein's lab over the past six years. Students examined budding yeast in the experiments because yeast cells exhibit similar characteristics and functions to human cells. Historically, discoveries made in yeast have led to breakthroughs in understanding and treating a number of human diseases.

A deeper look into human cells

Imagine driving in a car and going through a tunnel to get across a mountain. The car breaks down in the middle of the tunnel, causing a traffic jam. How do you get the car out of the way to allow others to travel through the tunnel?

Rubenstein said this example portrays what happens in all cells, including human and yeast cells, a process that he and his students examined in their experiments with budding yeast.

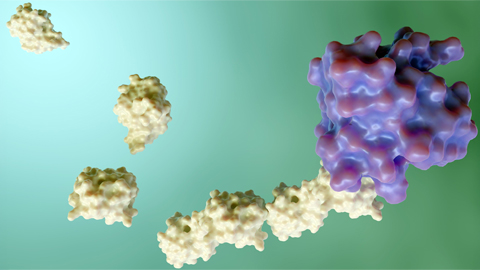

Cells have small tunnels called translocons that allow protein molecules to move around. Protein molecules play vital roles in our body, including controlling tissue and organ function, regulating metabolism, and more.

Sometimes, a protein "breaks down" when moving through a tunnel. Rubenstein explained that this leads to a backlog of proteins that cannot pass through the clogged tunnel and get to where they need to perform their essential functions.

Rubenstein and his students wanted to know how cells remove the clogging protein.

Like a car stuck in a mountain tunnel that needs a tow truck, a similar process happens in cells.

The discovery

To ultimately get to their solution, Rubenstein and his students had to create a "traffic jam" of their own.

"In the lab, students would send molecules into yeast cells that were designed to clog the tunnels at a high frequency," Rubenstein said. "It's sort of like driving an old junker into a tunnel that you're pretty sure is going to break down halfway through. We would then try to figure out which enzymes recognized and pulled out those clogging protein, which led to our discovery."

The group discovered that two enzymes called Hrd1 and Ste24, nicknamed "tow truck molecules," work together to unclog the blocked cell tunnel by dismantling the broken-down protein.

"It's known that these tow trucks protect humans from multiple diseases, including premature aging, diabetes, cholesterol, and autoimmune disease," Rubenstein said.

These tunnels, the group believes, also may become clogged in patients with diabetes.

"Our discovery that these enzymes work together to unclog those tunnels suggests that if we can design a medication that would make those enzymes work even more efficiently, we might be able to better treat diabetes," Rubenstein said. "We can power up those tow truck molecules in some way, or perhaps call more tow trucks to the scene."

Exemplary student work

The students, who designed and performed all experiments for this project, initially submitted their paper to the Journal of Biological Chemistry in April 2020, but it was rejected. The reviewers wanted Rubenstein and students to perform new experiments — a task entirely in the students' hands.

Graduate students Kyle Richards and Samantha Turk spent this past summer on Ball State's campus when the labs opened under new COVID-19 guidelines, which required them to wear masks and maintain social distance. Richards and Turk had both worked in Rubenstein's lab prior to the COVID-19 lockdown, and while other students had also worked on this research, they had all graduated from Ball State by this point. It was imperative that these two returned in the summer to continue the research after the paper was rejected.

"Our initial rejection came with comments for us to provide further evidence if we wanted to re-submit our paper," said Richards, a graduate research assistant in the biology department. "Samantha and I spent most of the summer working on extra experiments based on these comments. I verified that every yeast strain we used was exactly what we said it was. Samantha worked to give more evidence that the results seen in our experiments were directly related to the function of the Hrd1 and Ste24 tow trucks."

Their hard work paid off. In November, the group's work was published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

The six students that contributed to the accepted paper were Avery M. Runnebohm, Kyle A. Richards, Courtney Broshar Irelan, Samantha M. Turk, Halie E. Vitali, and Christopher J. Indovina.

"In the lab, I did a lot to expand on the work previously done by former Rubenstein lab members Avery, Halie, Courtney, and Christopher. My work was to study how these two enzymes may interact with the translocon tunnel," Richards said. "This work has potential implications for diabetes and cancer, and I'm grateful to have been a part of such exciting research."

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Indiana Academy of Science, and the Sponsored Projects Administration office at Ball State. Furthermore, three students applied for and were awarded research funding from the University.

"I'm really grateful for the way in which Ball State as a whole and the biology department has supported student research," Rubenstein said. "It is so valuable to have a department of excellent colleagues, who I can collaborate with and bounce ideas off of, and a pool of outstanding students to work with. The students in our department are really stellar."

Future research

Rubenstein and his students plan on continuing this research.

The next steps include focusing on how the tow truck molecules get called to the scene and how they perform their work, which could inform the development of improved treatments for human disease.

"We're doing basic research. While we're not directly curing diseases in our lab, we are making fundamental discoveries about how cells function," Rubenstein said. "This is crucial for the broader biomedical enterprise to be able to develop treatments for diseases, like diabetes. I think it's really valuable that Ball State values basic research and these types of discoveries that are foundational for understanding and treating human disease."

This article was originally published on the Ball State University Blog.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Engineering the future with synthetic biology

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on synthetic biology, featuring applications to better human and environmental health.

Scientists find bacterial ‘Achilles’ heel’ to combat antibiotic resistance

Alejandro Vila, an ASBMB Breakthroughs speaker, discussed his work on metallo-β-lactamase enzymes and their dependence on zinc.

Host vs. pathogen and the molecular arms race

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on host–pathogen interactions, to be held Sunday, April 13 at 1:50 p.m.

Richard Silverman to speak at ASBMB 2025

Richard Silverman and Melissa Moore are the featured speakers at the ASBMB annual meeting to be held April 12-15 in Chicago.

From the Journals: JBC

How cells recover from stress. Cancer cells need cysteine to proliferate. Method to make small membrane proteins. Read about papers on these topics recently published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

ASBMB names 2025 JBC/Tabor Award winners

The six awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2024 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.