Lipid control of nutrient signaling

The study of phosphoinositides, or PIs, has been in vogue for some time, as this minor class of short-lived membrane phospholipids regulates many of a eukaryotic cell’s physiological functions, including cell polarity, cytoskeletal dynamics, and membrane traffic and signaling. Recent data reveal a mechanism based on local PI generation that couples cell signaling to cellular nutrient status (1).

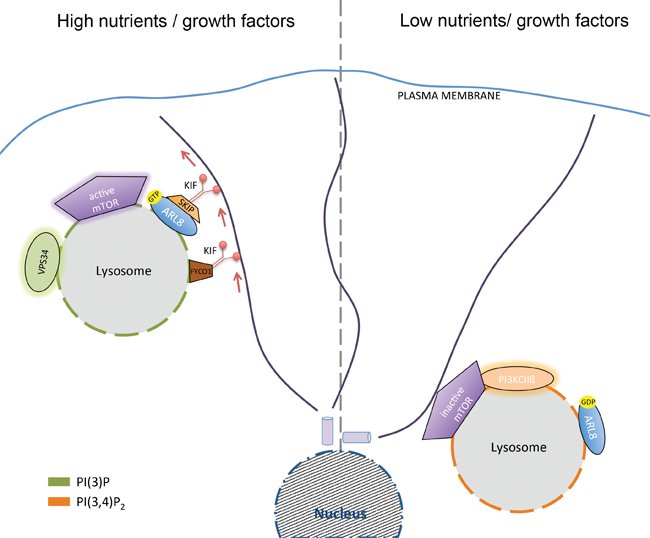

Left: Kinesin-mediated dispersion of lysosomes containing PI(3)P synthesized by Vps34 under conditions of high nutrient and growth factor availability activates mTORC1. Right: Perinuclear concentration of lysosomes containing PI(3,4)P2 synthesized by class II PI3Kbeta under conditions of nutrient and/or growth factor deprivation represses mTORC1 activity. courtesy of volker haucke

Left: Kinesin-mediated dispersion of lysosomes containing PI(3)P synthesized by Vps34 under conditions of high nutrient and growth factor availability activates mTORC1. Right: Perinuclear concentration of lysosomes containing PI(3,4)P2 synthesized by class II PI3Kbeta under conditions of nutrient and/or growth factor deprivation represses mTORC1 activity. courtesy of volker haucke

Different PIs display distinct subcellular distributions, with PI 3-phosphates such as phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate, or PI(3)P, and phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosph ate, or PI(3,5)P2, being found predominantly within early and late endosomes or lysosomes. The lysosome, via the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1, or mTORC1, acts as a central metabolic control hub that integrates extracellular growth factor signals with the cellular nutrient and energy status to direct the cell into either an anabolic or a catabolic state (2,3).

Disruptions in mTORC1-mediated lysosomal signaling are implicated in diseases such as diabetes, cancer and neurodegeneration. Lysosomal mTORC1 activity depends on growth factor signals that trigger the class I-PI3K-mediated synthesis of plasma membrane PI(3,4,5)P3, which stimulates mTORC1 via its effector Akt (2,3).

Researchers now have uncovered control mechanisms elicited by local PI signals at late endosomes/lysosomes that integrate lysosomal mTORC1 activity with cellular nutrient status. Growth-factor deprivation causes the late endosomal/lysosomal recruitment of class II PI3Kbeta, which locally produces a late endosomal/lysosomal pool of phosphatidylinositol 3,4-bisphosphate, or PI(3,4)P2, that suppresses mTORC1 activity (1). How exactly such suppression occurs is only partly understood, but one important element appears to be the recruitment of inhibitory 14-3-3 proteins to the mTORC1 subunit Raptor by local PI(3,4)P2 (1).

These findings are surprising given the established function of plasma membrane PI(3,4)P2 synthesized downstream of class I-PI3Ks in the activation of mTORC1 via Akt in growth factor-activated cells. These findings suggest a model whereby local PI switches at late endosomes/lysosomes sense and control cellular nutrient status to regulate mTORC1 activity (1). Consistent with this, late endosomal PI(3)P (4) and PI(3,5)P2 have been shown to activate mTORC1 locally — for example, by association of PI(3,5)P2 with the Raptor subunit of mTORC1(5) — under conditions of ample growth factor and nutrient supply.

As always in a fast-moving field, many open questions remain. For example, recent studies have revealed a surprising, though mechanistically poorly understood, link between lysosome position and nutrient signaling via mTORC1. Peripheral lysosomes display elevated mTORC1 activity compared with perinuclear lysosomes (6). How local pools of PI(3)P or PI(3,4)P2 couple lysosome position to the activity status of mTORC1 is essentially unknown. One possibility is that some of the factors that control lysosome position and/or mTORC1 signaling are regulated by the local PI content. PIs also may modulate the association of mTORC1 components with the lysosomal transport machinery. For example, PIs might regulate the recently described interaction between the Arl8-activating BLOC1-related complex and the mTORC1-associated Ragulator/LAMTOR complex (7).

Interestingly, PI(3)P synthesis by the class III PI3K Vps34 has been shown to facilitate the recruitment of the kinesin-1 adaptor FYCO1 to late endosomes/lysosomes (4). How the resulting dispersion of late endosomes/lysosomes to the cell periphery then causes elevated mTORC1 signaling is unclear. As lysosomes contain a variety of other PI lipids, including PI(4)P and PI(4,5)P2, further unanswered questions are whether and how these lipid pools may be subject to nutrient regulation or, conversely, contribute to the coupling of lysosome function and position to nutrient signals.

We thus face exciting times for lipid biochemistry, as lipids have taken center stage in many aspects of cell physiology. Understanding how local lipid signals sense and control cellular nutrient status at distinct subcellular locations will remain an important area for future studies.

References

1. Marat, A.L., et al., Science 356, 968 (2017).

2. Hardie, D.G., Cell. Metab. 20, 939 (2014).

3. Zhang, C.S., et al., Cell. Metab. 20, 526 (2014).

4. Hong, Z., et al., J. Cell Biol. (2017).

5. Bridges, D., et al., Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 2955 (2012).

6. Korolchuk, V.I., et al., Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 453 (2011).

7. Pu, J., Keren-Kaplan, T., and Bonifacino, J.S., J. Cell Biol. (2017).

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Sizing up cells: How stem cells know when to divide

Stanford University researchers find that stem cells control their size early in cell division across living multicellular systems.

When oncogenes collide in brain development

Researchers at University Medical Center Hamburg, found that elevated oncoprotein levels within the Wnt pathway can disrupt the brain cell extracellular matrix, suggesting a new role for LIN28A in brain development.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.