Invisible and undervalued: Navigating caregiving and careers in STEM

Karlett Parra’s brother has advanced diabetes and related complications. She is his full-time caregiver, which means she needs to monitor his symptoms, keep track of his medications, accompany him to countless doctor’s appointments and more.

Parra is also a professor and chair of biochemistry and molecular biology at the University of New Mexico. She studies vacuolar adenosine triphosphatase proton pumps, has mentored over 70 trainees, received many awards and published dozens of scientific papers. However, she said her caregiving responsibilities have taken a toll on her career.

“At first, I thought I have to do one or the other,” Parra said. “Now I have learned that I can handle both. But it is draining. After five years (of caregiving), the fatigue is here physically, mentally and emotionally. It’s a roller coaster.”

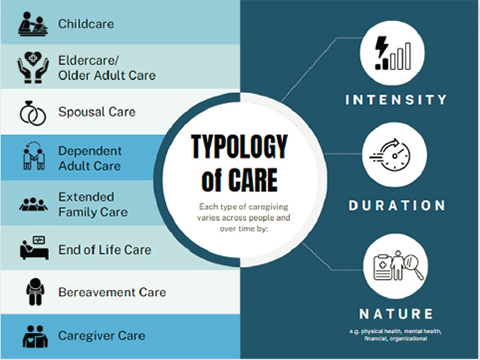

Parra, who is a member of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Women in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Committee, or WiBMB, said caregiving does not just apply to one’s children, but also to spouses, parents, siblings and others. She added that, though the policies at her university are supportive, they are fragmented and do not accurately represent this definition of caregiving, like those at other institutions.

In fact, 13 states have passed paid family and medical leave laws. However, policies in some of these states have not yet been enacted and do not require the employer to pay 100% of an individual’s salary during the leave period.

The authors of a recent national report state that the labor and contributions of caregivers in the U.S. are often “invisible and undervalued.”

The report

The National Academies of Science and Medicine published “Supporting Family Caregivers in STEMM: A Call to Action” in April. The report showed how the labor and contributions of caregivers are often undervalued, and it provides best practices for implementing caregiver support policies at the institutional, state and federal levels.

Care is one of the most universal human activities, which many Americans provide throughout their lives, the authors wrote. Yet, stigma and barriers exist within the U.S. workforce for caregivers.

In 1993, Congress passed the Family and Medical Leave Act, which requires employers to provide employees with job-protected, unpaid leave for medical and family reasons.

However, in the U.S., no employer is required to provide paid, caregiving leave. This is in stark contrast with policies in Europe. Within the European Union, employers must grant a minimum of 14 weeks of maternity leave and two weeks of paternity leave as of 2022. Many countries, including Italy, Estonia, France, Luxembourg and the Netherlands have more generous policies that grant mothers their full salary during the leave period.

In their report, NASEM committee members called on the federal government to mandate that employers provide 12 weeks of paid caregiving leave.

“Most of us have firsthand experience with caregiving, yet family caregiving can be a taboo topic in many sectors of academic STEMM (science technology, engineering, mathematics and medicine),” Elena Fuentes–Afflick, NASEM committee chair and professor of pediatrics and vice dean of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, stated in a press release. “We hope our report brings attention to caregivers and stimulates discussion about ways we can better support caregiving at all levels.”

The authors concluded:

- Federal, state and institutional policies to support caregivers are inadequate and require innovation.

- Lack of caregiver support perpetuates institutional inequity.

- Caregiver support is needed to bolster the U.S. scientific enterprise.

Based on these findings, they made the following recommendations:

- Congress should enact legislation to mandate a minimum of 12 weeks of paid caregiving leave.

- Institutions should provide trainees and faculty with paid family and/or caregiver leave and flexibility.

- Institutions should make caregiver resources, including information and child care, easily accessible.

- Institutions should collect and analyze data on caregivers to ensure adequate policies.

- Federal and private funders should facilitate the leave and reentry processes and grants for those who take leave.

Inequality across institutions

Susan Baserga, a professor of molecular biophysics and biochemistry at Yale University School of Medicine and chair of the ASBMB’s WiBMB Committee, served as a caregiver to her now-grown son and to her parents. When she had her son in the 1990s, Baserga enjoyed six weeks of paid parental leave and on-site day care at the Phyllis Bodel Childcare Center at Yale once her son was three months old.

“The day care was started by women faculty in 1979, who could see the future,” Baserga said. “I am shocked not everyone has access to on-site day care by now — almost 45 years later.”

Baserga is in the minority of parents who experience such benefits. According to the Association for Human Resources Professionals in Higher Education, fewer than 40% of higher education institutions offered paid parental leave to new parents as of 2021.

Changing caregiving culture

Both Baserga and Parra said policy changes are needed, but also a culture shift.

Authors of the NASEM report stated many women caregivers experience flexibility stigma, or “negative evaluations and/or treatment of individuals who make use of policies designed to allow greater flexibility in work schedule.”

According to the Department of Labor, 6.9% of workers said they needed family and medical–type leave but did not take it. Their reason: They couldn’t afford to take unpaid leave.

“We have to change the culture,” Parra said. “And I think leadership plays a key role in that. … We all need to talk openly about the policies and our experiences.”

According to the authors, the lack of caregiving policies perpetuates inequity but also leads to attrition of women in science, thus harming the U.S. scientific enterprise.

Baserga said she tries to set an example in her department by speaking up often about her son and her caregiving experiences.

“We may as well just be open about it because then we can better exchange information,” Baserga said. “If we keep everybody in the dark, they're not going to be able to benefit from all the battles that we’ve fought.”

Although Parra said her caregiving responsibilities take a toll on her, she has no regrets and would do it again for a loved one. “I couldn’t live with myself if I didn’t give them all the help that they need from me.”

She said her brother’s courage in the face of his health challenges motivates her.

“You have to be proud of your decisions,” Parra said. “The greatest thing, so far, is that (caregiving) helped me to see the world in a different way. … I want to do something bigger than myself. There is more than just my lab and my pipettes; the world is bigger.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Policy

Policy highlights or most popular articles

Embrace your neurodivergence and flourish in college

This guide offers practical advice on setting yourself up for success — learn how to leverage campus resources, work with professors and embrace your strengths.

ASBMB honors Lawrence Tabak with public service award

He will deliver prerecorded remarks at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting in Chicago.

Summer internships in an unpredictable funding environment

With the National Institutes of Health and other institutions canceling summer programs, many students are left scrambling for alternatives. If your program has been canceled or delayed, consider applying for other opportunities or taking a course.

Black excellence in biotech: Shaping the future of an industry

This Black History Month, we highlight the impact of DEI initiatives, trailblazing scientists and industry leaders working to create a more inclusive and scientific community. Discover how you can be part of the movement.

ASBMB releases statement on sustaining U.S. scientific leadership

The society encourages the executive and legislative branches of the U.S. government to continue their support of the nation’s leadership in science.

ASBMB and advocacy: What we accomplished in 2024

PAAC members met with policymakers to advocate for basic scientific research, connected some fellow members with funding opportunities and trained others to advocate for science.