What’s in the structural vaccine designer’s toolbox?

Vaccines work by introducing an antigen and training the immune system to raise neutralizing antibodies. One challenge in vaccine design is that many viral surface proteins are shape shifters, undergoing radical conformation changes during the process of infection. Antibodies that target the wrong conformation may do little to prevent infection. Vaccines that present only one stabilized conformation surmount this problem — but they sometimes take some protein engineering.

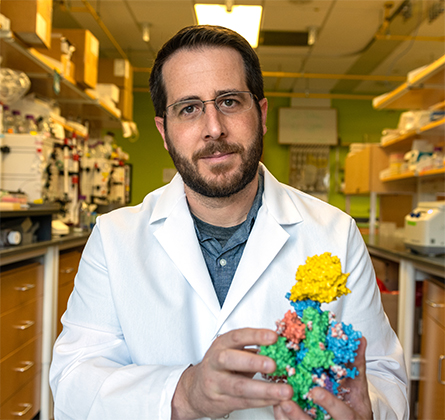

Not long after the SARS-CoV-2 genome was reported, Jason McLellan’s lab determined the structure of its spike protein and made a key substitution, adding two proline amino acids to stabilize the antigen in a shape the immune system targets more effectively. Pfizer, Moderna, Novavax and Johnson & Johnson used this modification in their COVID-19 vaccines.

In recognition of this work and his team’s continuing studies of the virus that causes COVID-19, McLellan has received several prizes this year. From the Texas Academy of Medicine, Engineering, Science and Technology, he received the O’Donnell Award. He was a national finalist for the Blavatnik Prize, and he recently received the inaugural McGuire Prize, which recognizes high-impact work by a member of the Dartmouth College community. (McLellan was a professor at Dartmouth before moving to his current position at the University of Texas at Austin.)

ASBMB Today talked to McLellan about how his lab approaches protein engineering for vaccine design, the noncoronavirus projects they are pursuing and future pandemic preparedness. This interview has been edited.

Tell me about how your lab tackles vaccine design.

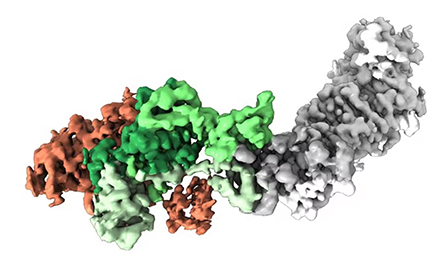

We start with a protein structure, usually from X-ray or electron microscopy. Then, once we have the structures, we’re ready to analyze the protein and figure out the optimized sequences that we want to use for an antigen. Recently, we’ve been working at UT with the Machine Learning Lab, a really excellent computer science group, to try to predict which substitutions will increase melting temperature. That’s been fun. They don’t know much about proteins, I don’t know much about machine learning, but we’re making solid progress.

Many times, we first need an antibody to stabilize and trap a protein and then engineer the molecule to use as a vaccine. Sometimes we are able get the structure and engineer a molecule that we then use as bait to pull out antibodies (from recovered patients’ serum) to use for antibody-based prophylaxis. So it’s really nice synergy.

Let’s say you have a bunch of conformations from a protein that’s shifting around. What’s in the protein engineering toolbox for stabilizing it?

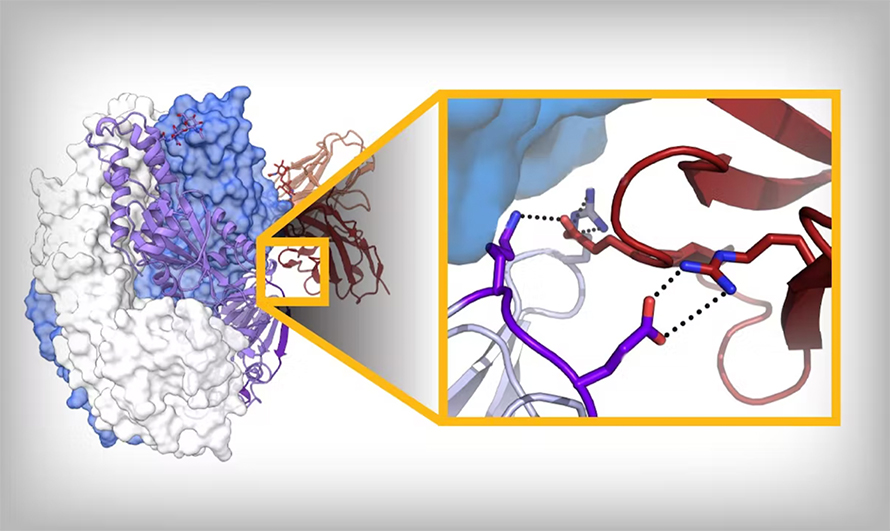

Depending on the protein, there are different approaches for structure-based vaccine design. Something that we’re known for is stabilizing class 1 viral fusion proteins, which start off in one conformation (pre-fusion), go through a series of rearrangements and end up in another (post-fusion). (Author’s note: McLellan’s lab has worked on proteins in this family from coronaviruses, respiratory syncytial virus, metapneumoviruses and others.)

We generally know both conformations, and we can infer intermediates; we know pretty well now which region unfolds first, followed by what’s next. And not the whole protein changes, either; about 50% stays the same. So we can start to say, “How can we make amino acid substitutions that bond moving regions to the nonmoving region?”

In some of the best cases, you can get a disulfide bond: One cysteine in the unmoving, one cysteine in the moving, and that just locks it — as long as that bond forms. Otherwise, we try to fill little cavities. You’re generally taught that proteins are packed very well for stability, which is true, but not for a protein that has to undergo conformational change; it needs to have evolved instability. So we try to find those regions that are unstable. Those are some of the tricks: We’re trying to add salt bridges, add hydrogen bonds, fill cavities, make disulfide bonds and use prolines to help reduce backbone flexibility.

Gotcha. Does the cavity filling use a small molecule?

No, amino acid side chains. For example, in the case of respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, F protein, there is a pocket with a serine pointing toward it. We mutated that to phenylalanine, and the phenylalanine just fills the pocket. And so now you’re getting some additional van der Waals interactions and also making it really unfavorable to pull that phenylalanine into a solvent of water molecules. We actually have considered using small molecules to stabilize that; it just becomes a little unclear as a Food and Drug Administration regulatory issue: Is it an excipient? So we try to do it with amino acid substitutions, generally small to large.

You mention RSV; I understand there’s an RSV vaccine study underway that uses a stabilized antigen you developed. Besides phenylalanine, what else worked best to stabilize that antigen?

So the one I created at the Vaccine Research Center (at the National Institutes of Health) has a disulfide and two cavity-filling substitutions, and that was enough to lock it. One of the big companies has licensed that one. Among other companies — GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer and Janssen — it’s not actually clear what they’ve chosen. But it’s essentially the same molecule, just a different substitution. I think in the big three, it’s primarily disulfide bonds, cavity-filling substitutions — and a proline. Janssen has a proline one that was beautiful and was our inspiration for the coronavirus proline stabilization.

I’ve worked with Janssen since 2013, so I solved the structure of their prefusion RSV F protein, and this proline — how it works is beautiful. When we got the structure of the coronavirus HKU1 spike when I was at Dartmouth, we decided to proline scan this region, and that worked. (Author’s note: HKU1 is a coronavirus first found in humans in 2004.) We got the two prolines in this region that work to stabilize MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV, and ultimately that was incorporated into all the SARS-CoV-2 vaccines authorized for use in the U.S.

How much of your process is design, and how much is just trying things out?

There has to be some trying things out, because protein folding is such a black box. There are changes we make that you bet with as much as you can that it’s going to work, and then you try to express it and there’s nothing. There’s no protein made. Presumably at some intermediate, there’s some folding thing. But we’re not at a state where we can predict that yet. So what we’re trying to do is go from an infinite number of permutations down to at least a testable number of 100 or so and then do combinations. We’d love to start to use more machine learning and narrow it down even more. The experimental part is the slowest part. So if we can even triage for an earlier stage, that would help speed things up.

Some people will still say that the protein folding problem hasn’t been solved because we don’t know anything about the folding intermediates in the pathway or what folds first. AlphaFold looks at coevolution to give you the final structure — which is different than all our simulations with explicit water molecules that really try to tease out what is folding and how. (Editor’s note: To learn more about AlphaFold, turn to page //.) We don’t know that. It gives us the final answer, which in many cases is good enough. But sometimes, if we actually could understand the folding problem, we’d probably realize why some of our substitutions kill expression or don’t work well.

You mentioned sometimes starting with an antibody to lock your antigen into one shape. Where do you go looking for those antibodies?

In my lab, we don’t do the antibody isolation, but we partner with a lot of people who do. The best antibodies are often from people who have recovered from an infection. A lot of it does come down to sample access: Who has access to rare disease samples? It was really hard getting blood samples of MERS-CoV survivors. But fortunately, for respiratory syncytial virus and metapneumovirus, we can just bleed our friends; we’ve all been infected at some point. It’s the more exotic ones where it could be hard to obtain them.

I could imagine those rare infections could also be the ones that you’re potentially a little bit more concerned about?

Yeah. There’s a big push for prototype pathogen pandemic preparedness and trying to figure out, of the 26 viral families, which ones are most likely to cause a pandemic so we can start doing prospective vaccine development.

We might not know which family member emerges as the pandemic threat. But maybe we will have already learned things that can be applied broadly to the family, in much the same way we first stabilized MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV and HKU1, which allowed us to stabilize SARS-CoV-2 even though it wasn’t on our radar. Trying to get some of these things that are more exotic, it can be tricky. There might not be many human infections — something like Nipah virus doesn’t affect a lot of humans each year — but that’s a major target now.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Mydy named Purdue assistant professor

Her lab will focus on protein structure and function, enzyme mechanisms and plant natural product biosynthesis, working to characterize and engineer plant natural products for therapeutic and agricultural applications.

In memoriam: Michael J. Chamberlin

He discovered RNA polymerase and was an ASBMB member for nearly 60 years.

Building the blueprint to block HIV

Wesley Sundquist will present his work on the HIV capsid and revolutionary drug, Lenacapavir, at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, in Maryland.

In memoriam: Alan G. Goodridge

He made pioneering discoveries on lipid metabolism and was an ASBMB member since 1971.

Alrubaye wins research and teaching awards

He was honored at the NACTA 2025 conference for the Educator Award and at the U of A State and National Awards reception for the Faculty Gold Medal.

Designing life’s building blocks with AI

Tanja Kortemme, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, will discuss her research using computational biology to engineer proteins at the 2026 ASBMB Annual Meeting.