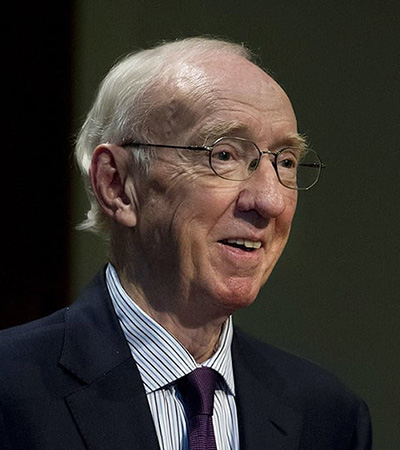

In memoriam: Bengt Samuelsson

Bengt I. Samuelsson, a professor of medical biochemistry and biophysics at the Karolinska Institute, a lipid biochemist and a Nobel laureate died July 5. He was 90, and he had been a member of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology since 1976.

Samuelsson was born May 21, 1934 in Halmstad, Sweden. He completed undergraduate studies at the University of Lund in southern Sweden and then moved to the Karolinska Institute for graduate work in biochemistry. In 1960, he earned his doctorate under the mentorship of Sune Bergström, studying prostaglandin structural biology, and then in 1961 he obtained a medical degree. In 1962, he briefly moved to Harvard University for a research fellowship in the before returning to the Karolinska Institute in the same year to join the faculty.

Over the next 16 years, Samuelsson worked at multiple institutions including as a visiting professor at Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology until he became dean of the medical faculty at the Karolinska Institute from 1978 until 1983. Samuelsson shared the 1982 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with John Vane and his doctoral mentor, Sune Bergström, for their discoveries concerning prostaglandins and related biologically active substances. Then, from 1983 to 1995, Samuelsson served as president of the Karolinska Institute.

Bergström, his doctoral mentor, had also served as both dean and president of the Karolinska Institute, as well as sharing the Nobel Prize. A JBC classics article describes the partnership between Samuelsson and Bergström in detail.

Prostaglandins are a family of oxidized derivatives of arachidonic acid that play crucial roles in various physiological processes, including inflammation, body temperature regulation, thrombosis, and allergic reactions. Samuelsson authored 324 publications that have been cited over 46,000 times and by more than 350 patents. In a 1974 PNAS paper that has been cited over 1,200 times, he demonstrated that homogenized sheep glands can convert [1-14C]arachidonic acid to prostaglandins G2 and H2. Notably, both of these prostaglandins are known to induce aggregation in human platelets. In a 1975 PNAS paper that has been cited over 3,600 times, Samuelsson reports the discovery and structure of thromboxane A2, which is a biologically active compound produced by human platelets during the conversion of prostaglandin G2 to thromboxane B2. Ischemic stroke, one of the leading causes of death and disability worldwide, is particularly associated with the activation of the thromboxane A2 receptor. Samuelsson’s research on prostaglandins, thromboxane, and related biomolecules, identified the agents and their production processes. This foundational work has later facilitated a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying ischemic stroke.

Göran K Hansson, a professor of medicine, talked about the significance of Samuelsson’s work in a Karolinska Institute obituary.

“Very few scientists can open up a whole new field of knowledge. But that is what Bengt Samuelsson did,” Hansson said. “Based on Ulf von Euler's and Sune Bergström's discovery of prostaglandin, he mapped an entire biochemical continent of signaling molecules in the human body, and found that they are of great importance in the blood circulation, the respiratory system, the genitals, the immune system, the nervous system and almost the entire body.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Meet Donita Brady

Donita Brady is an associate professor of cancer biology and an associate editor of the Journal of Biological Chemistry, who studies metalloallostery in cancer.

Glyco get-together exploring health and disease

Meet the co-chairs of the 2025 ASBMB meeting on O-GlcNAcylation to be held July 10–13, 2025, in Durham, North Carolina. Learn about the latest in the field and meet families affected by diseases associated with this pathway.

ASBMB recognizes 2025 outstanding student chapter

The Purdue group, led by Orla Hart, developed STEM outreach initiatives for low-income and minority students in Lafayette, Indiana.

ASBMB inducts 2025 honor society members

Chi Omega Lambda, which recognizes exceptional juniors and seniors pursuing degrees in the molecular life sciences, has 16 new inductees in 2025.

2025 voter guide

Learn about the candidates running for ASBMB President, Secretary, Councilor, Nominating Committee and Publications Committee.

Meet Paul Shapiro

Learn how the JBC associate editor went from milking cows on a dairy farm to analyzing kinases in the lab.