‘We love to see the hard work of undergraduates come to life’

Over the past two decades, thousands of students have cut their science communication teeth at the undergraduate poster competition at the annual meeting of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

Begun in 1997 by postdoc Catherine Drennan (now a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology), the event has grown in both participation and impact.

It has helped undergrads become more competitive for graduate programs and find supportive mentors. It has helped educators connect with colleagues, launch collaborative projects and secure funding. And it serves as an annual reminder, as Drennan said, that it’s unwise to underestimate undergrads.

Phillip Ortiz, assistant provost for undergraduate and STEM education at the State University of New York, has helped orchestrate the poster competition since the early days and said it’s his favorite part of the ASBMB meeting. “The energy in there is just so wonderful,” he said. “It has that feeling of any competition: the sort of a tingle of excitement, fear and anticipation.”

Kathleen Cornely of Providence College, chair of the poster competition committee, echoed Ortiz: “This is why it’s so popular — because you walk into the room and that energy is incredible.”

This is the first time many competitors have presented on a national stage, Ortiz said. And many, Cornely added, come with an entourage.

“It’s loud because there are so many great conversations being had,” Cornely said. “The students’ friends are there, so you might see a little crowd gathered around a poster.”

The judges also are revved up. Many, Cornely said, show up early.

Ortiz concurred: “For a lot of (judges), this is their primary contact with undergraduate students, so they’re getting to show their mentoring chops and talk to students who are tremendously engaged in their research.”

The society expects almost 300 students and more than 150 judges to participate during the annual meeting in April in Philadelphia.

Over the years, ASBMB Today has reported on aspects of the poster competition, but it’s never attempted to capture the big picture — until now. For this joint reporting project, we interviewed people who’ve made the event possible and who’ve benefited from their experiences — as organizers, judges, mentors and participants. We discovered that the competition has a way of getting its claws in you — enticing you to return year after year.

A seat at the table

The poster competition was conceived to achieve multiple goals, Drennan and Ortiz said. The society wanted to attract younger members and make sure they were well served.

“We’ve often thought of the undergraduate poster competition as a way of certainly bringing people into the society but also demonstrating that the society is not just about researchers but also about learning,” Ortiz said.

The ASBMB’s founders established criteria that limited membership to the most accomplished and credentialed scientists, which meant that, in the early days, young scientists, women and people from marginalized groups were few and far between.

The history book “100 Years of the Chemistry of Life: The ASBMB Centennial History” by Ralph Bradshaw and colleagues records how society leaders debated those exclusionary criteria in the 1980s and abandoned them in the 1990s, effectively converting the ASBMB “to a society embracing a much broader range of individuals with an interest in the biochemical sciences.”

Aware that they needed to do more to make the society relevant to forthcoming generations of scientists and to make its membership more diverse, the leadership held a retreat in 1995 in California to do some strategic planning. Among those invited was Drennan, then a grad student.

Drennan said she doesn’t know who decided it might be good to have a grad student at this meeting talking about the future of the society, “but it just became very clear to me that the ASBMB wasn’t doing enough to embrace young scientists who were interested in biochemistry and that we could do a whole lot more.”

She suggested a poster session to attract undergrads to the national meeting.

“People were like, ‘Well, I don’t really think that undergrads are going to necessarily come. It’s such a big meeting’ and all these things,” Drennan said. “And I was like, ‘Let’s see if we can give them a reason to come.’”

Also up for debate was the timing of the session.

“Originally it was put at the beginning of the meeting, because, honestly, some people thought it would be a huge disaster and last one year,” she said. “We could just stick it in the front, and they would show me that this was not going to work.”

Ortiz too recalled that timing was a sticking point. “At one point it was at the midpoint of the meeting … which was problematic because we always thought of the poster competition as a way to help students prepare for the main meeting,” he said. “And then we shifted it (back) to the afternoon of the opening plenary,” where it remains.

“A lot of the undergrads meet each other doing it, and then they have a buddy for the meeting,” Drennan said.

Judging: Why and how

Drennan had concerns. One big worry was that not every participant would enjoy the experience.

“I had attended one meeting where my poster was in the very back — like in the last row of a giant room — and I don’t think anyone made it that far. And I was like, ‘I put all this work into this poster!’” she said. “I didn’t want no one to look at an undergrad’s poster if they put all this time into it.”

Cornely agreed: “Maybe you’re standing by your poster and nobody comes by … Sometimes being at a poster during a big meeting can be a great experience, but sometimes it’s not.”

The solution? Judges.

“If you’re at the poster competition, you know that you’re going to have judges paying rapt attention to what you’re saying,” Cornely said.

Drennan made it a point to invite textbook authors to serve as judges, because “textbook authors are people who undergraduates have heard of.”

Judy and Donald Voet — authors of the gold standard in biochemistry texts — were among the judges at the first competition in 1997.

“I went around and said, ‘You see that person? That’s Judy Voet of Voet and Voet,’ and the students’ eyes were wide,” Drennan said. “And then they met Judy Voet, and she was really nice and engaged. That was just beyond exciting.”

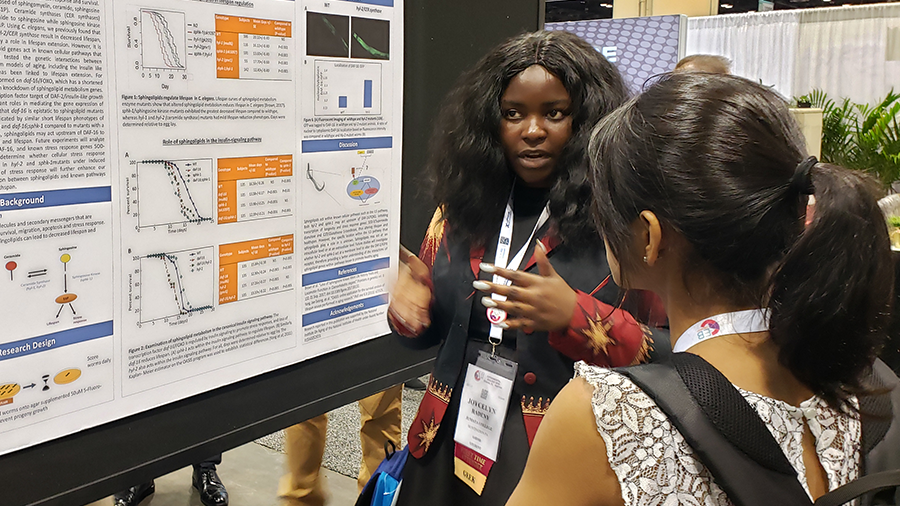

Being a participant

Some of the 2021 winners said they were nervous about the poster competition, but that nervousness was tinged with excitement.

Mlana Lore, a recent graduate of Eckerd College, is now a grad student at the University of Colorado. She won last year’s microbiology and RNA category.

“It was definitely nerve-racking … I was used to small local conferences,” she said. “Right before talking to the judges, I was anxiously double-checking my poster for mistakes but also excited to talk about the research that I had spent the majority of my undergraduate time working on.”

For Anna Corradi, a recent graduate of Bemidji State and now a grad student at University of North Dakota, the stakes felt high.

“As the time got closer to present my data, I began to feel nervous, knowing that this would be the last time I was able to present my undergraduate research project that I poured years of work into,” said Corradi, who won in one of the cell biology and signal transduction categories.

As the competition went on and the students began to interact with the judges, some of their nerves began to dissipate.

Natalie Botros, a student from the University of San Diego, said that all the judges she spoke to “had a genuine interest in my overall project, data and future research goals and were excited to learn more.” Botros’ poster presentation was the winner of one of the protein structure, function, synthesis, degradation and enzymology categories.

Even if it’s stressful, talking to the judges is an important part of undergraduate research development.

Shawn Lin at Wesleyan University, who took the prize for the DNA, chromosomes and gene regulation category, reports that the judges “were all very nice and encouraging” and were “excited to meet young researchers.”

The winners all urged future competitors to remember that, even if it feels like you performed poorly, the judges might see things differently.

“I was very surprised to see that I won! I felt like my conversations with the judges went all right but not spectacularly, and two judges had independently pointed out an error in my data presentation that I didn’t have much explanation for,” said Lore.

When Corradi finished talking to three judges, she said, she felt like she did well but also recognized that she could have done better. “When the awards were announced, and I saw my name on the list I was filled with so much joy,” Corradi said.

In addition, the winners all said they felt that their participation in the poster competition will help them in their career trajectory. Corradi notes that “these events were a great point of conversation during my graduate school interviews and allowed me to develop public speaking abilities.”

The winners underscored that science communication skills are key not only for the competition but for all aspects of scientific discourse.

Botros said she thinks “it is extremely important to be able to effectively describe and communicate the techniques and experiments performed to acquire data; this helps to promote reproducibility and understanding. Science communication allows the individual to answer questions regarding their research and communicate new scientific knowledge.”

Who judges are and what’s expected of them

Whereas you need only be an undergraduate and first author on an abstract to compete, not just anyone can be a judge. The organizers look for faculty members who have a good understanding of teaching and who can provide constructive feedback to the competitors.

“This is a formative moment for the students. You’re not here to make the students feel bad; you’re here to help them become better scientists and better presenters,” Ortiz said.

Postdocs are welcome to apply too. However, they should be prepared to participate in a training session on how to be a mentor and how to give constructive feedback.

That feedback can make a difference in real time. If the first judge takes a few minutes to explain how the presenter could do better, the presenter can turn around and apply that advice when the second judge comes over. And if the second judge offers additional advice, the competitor’s next attempt will be even better. Ideally, by the time the student is at their poster on the exhibit floor with everyone else at the meeting, their presentation will be top-notch.

Importantly, feedback goes both ways. The lead judges and organizers always are listening to the back and forth during the competition.

“And if we get a report that a judge may be, you know, a little harsh or not giving appropriate feedback, we coach that judge to being a better mentor,” Ortiz said.

Pamela Mertz of St. Mary’s College of Maryland, who chairs the ASBMB Student Chapters Steering Committee, emphasized that even though it’s a competition, the environment is overwhelmingly supportive.

“Everybody who’s there is super excited about undergraduate research, wants to help mentor undergraduate research, and wants to help the students think about their projects and be able to answer questions. In other words, it’s not a hostile environment,” said Mertz.

What it’s like to be a judge

Past judges told us that the undergraduate poster competition holds a special place in their hearts.

Chris Rohlman, a professor at Albion College, has been involved since 1997, serving as an organizer, judge and lead judge. “(It) started as a lunch with Cathy (Drennan) in Claremont, California, and in the first couple of years we ran it out of the hatchback of her car,” he recalled.One of Rohlman’s favorite memories, he said, relates to the close student–faculty connections that the poster competition facilitates.

“I was sitting with longtime ASBMB colleague and friend Marilee Benore (a professor at the University of Michigan–Dearborn) waiting for a plenary session when two of my students were talking about how they really wanted Michael Cox’s autograph in their Lehninger textbook. Marilee — being Marilee — marched my students to the front row of a giant plenary session and said to him, ‘These two young ladies would really like to meet you.’ That’s an example of an experience of how people that judge the poster competition really welcome undergrads there and help them to be excited about their science.”

Kristin Fox, a professor at Union College in New York state, is both a veteran of the organizing committee as well as a judge. For her, the competition stands out as a networking nexus not only for the students but also for the faculty. She said it attracts scientists, many repeat judges like her, who truly value undergraduate education and for whom teaching is a major part of their academic focus.

“A lot of us met at the undergraduate poster competition, judging together and having lunch together. We all care about teaching, and I mean really teaching,” she said.

This networking aspect even has resulted in active academic collaborations for Fox and colleagues, including a National Science Foundation pedagogy grant funding the Malate Dehydrogenase CUREs Community project involving protein-centric course-based undergraduate research experiences around the country.

Jeremy Johnson, a member of the poster competition committee and a frequent judge, said he also has “met ongoing collaborators, reconnected with colleagues and set up rotating seminar presentations” while at the event. A professor at Butler University in Indiana, he said he also has adjusted his in-class grading of presentations “to reflect the rigor” of the competition’s rubric.

Some judges are so psyched about participating that they even show up early, Cornely said.

“We tell them to come at 11:30 so that we can have a judges’ orientation and they can read their abstracts, and everyone comes early — sometimes hours early. And nobody’s reading abstracts,” she said. “Everyone is hugging and catching up on the joys and sorrows of the last year.”

Johnson said he’s one of the early birds: “I always show up early to reconnect with friends, to meet new colleagues, and to hear Phil give his speech about proper use of the scoring rubric.”

Once the competition is truly under way, each judge is assigned six posters.

During the first half of the competition, students with even-numbered posters present their work. A judge observes three presentations and reports to the lead judge which of the three could be real contenders. After a lunch break, the odd-numbered presenters have the floor, and each judge observes another three and again confers with the lead judge.

The experience can be rather frantic, Cornely said, and yet the judges are exceptionally loyal: “They come back and judge year after year, even though all they get out of this is a box lunch.”

Applications for prospective judges will be accepted beginning in January after the abstracts have been submitted, counted and reviewed. The number of judges selected will depend on the number of competitors, Cornely said.

Ortiz emphasized how important judges are to the success of the event.

“I think it’s really important to say that it would not work if we didn’t have the participation of a tremendous number of judges and organizers. And these people are volunteering their time. Without that, it would never work.”

What makes a winning presentation

If you’re a student reading this, you probably want to know what it takes to win. (Prospective judges might be curious as well.) There is no simple formula.

“We encourage the judges to look for content first. Is the poster clear? Is the poster coherent? Is the student able to explain the content thoroughly? Does the student have a deep understanding of what they’re presenting?” Ortiz said.

Keep in mind that some of the students might be presenting the results of eight-week summer projects, while others might have worked for one or more years. Some might have conceived of the projects themselves, and others simply might have taken over someone else’s project without a lot of background information.

“The students come in with a wide variety of expertise and insights. But yet, we still expect them to have an understanding of the fundamentals, the techniques, the results and the implications of those results,” Ortiz said.

Fox said the students who perform well are those who “clearly articulate the research they did and weren’t just following along to someone else’s research plan.”

For Drennan, what’s important is that the presenter “tells me a really cool story about what they’re doing.”

She explained: “There’s so much amazing science out there. But can you convey why what you’re doing is important in a way that gets others excited? … It’s a great way to practice communication skills.”

Sometimes she’s so hooked, she said, she’ll ask presenters to email her to let her know how the final experiment goes. “I need to know — if it’s an unfinished story — what the answer is!” she said.

Both Fox and Rohlman said one key question is at the root of the judging process: How well does the student understand the fundamentals of the research they did and why they did it? Both also emphasized a core tenet of the training for judges: It should be a positive experience for the student.

It’s not just about fancy schools or equipment

You might suspect that students with access to expensive instrumentation or decorated leaders in the field fare better in the competition than those without. Drennan wondered about this too when she first started the contest.

“I looked at the abstracts and I tried to kind of guess who might have the top posters, and I was largely wrong. Because sometimes people had more help writing, and other people, once you met with them, they just blew you out of the water.”

Rohlman, a repeat judge, said that judges consistently are impressed by the quality of the undergraduates’ work. “Whether they attend a small college or an R1 research institute, some undergraduate students just take their work and run, and end up working at the same level as graduate students. You can’t even tell the difference between their posters,” he said.

So the answer is decidedly no. You don’t have to be at an elite institution or have access to the newest technologies to win.

“Some of the undergrads who are at smaller schools with fewer resources often have a lot more time with their faculty member. And that is super important,” Drennan said. “Students from schools that maybe you hadn’t even heard of before were just doing the most impressive work. So that’s partly what I love about this — anybody can win,” Drennan said.

And even those competitors who don’t win prizes get to go home with written feedback. “Every student gets their judging forms back,” Ortiz said.

Joseph Chihade, a professor at Carleton College in Minnesota and a member of the poster competition committee, said that “while prize money and certificates are awarded, the real goal is to celebrate undergraduate work, to provide opportunities for students to get constructive feedback and mentoring, and to bring students into a broader scientific community.”

Chihade continued: “We make a tremendous effort and spend a lot of time worrying about being fair as we evaluate posters, but those awards are out there mostly to motivate students to do their best work, not to provide definitive judgments of what constitutes the ‘best’ science or presentation.”

Science takes a village

Daniel Dries participated in the poster competition when he was an undergrad. Today, as an associate professor and department head at Juniata College, he passes the torch year after year by taking his students to the meeting. (See sidebar “From presenter to mentor.”)

“The annual meeting is an opportunity for the free exchange of ideas: criticism, new collaborations and new questions you may not have thought to ask,” said Dries. “It is a great example of how science takes a village, and how we need to find the people within that village to advance our science and our professional goals.”

It’s not uncommon for students to return year after year, according to Johnson of Butler University.

“I have participants who I meet as a sophomore or junior and then they return as a senior. It is fun to see the progression of their research project and especially their intellectual growth as a scientist,” he said. “In addition, you see distinct students from many of the same undergraduate institutions and labs so you get to follow the progression of the research project over time.”

Drennan said she’s been glad to observe and contribute to the society’s efforts to “reach out to communities that might have felt like, when I started, a little bit left out. I’ve seen a lot of transformation, and I think the ASBMB should be really proud of what it’s done, especially when it comes to underrepresented researchers and being inclusive.”

She added that the poster competition “just shows the quality of science that’s being done everywhere, and the quality of work that undergraduates are doing. Never underestimate an undergraduate: They’re capable of so much.”

ASBMB Today contributors Leia Dwyer, Lisa Learman, Nicole Lynn and Sarah May contributed to this article.

From presenter to mentor

Daniel Dries chairs the chemistry and biochemistry department at Juniata College in Pennsylvania. He first attended the ASBMB annual meeting as an undergraduate at the University of Delaware under the guidance of Hal White, a previous ASBMB education award winner.

Dries helped establish the ASBMB student chapter at Juniata and serves as its faculty adviser. Every year, he said, he takes as many students as he can to the annual meeting. He noted that the society’s travel grants help a lot.

“One year, after the poster competition, I remember running into Natalie Ahn with my students. (She was) the president of ASBMB at the time,” he said. “Natalie had a great personal story about her experiences presenting research, what it means to be a scientist, and how to handle criticism. It was a fantastic opportunity for my students.”

Dries attributes his success to the encouragement and support of his many mentors.

“Being a good mentor is having the ability to utilize your knowledge and network to guide your students to their best possible future,” Dries said. “Hal taught me that education is more than being lectured at … When I take students to the annual meeting, it changes their perspective on what a scientific community is and the importance of networking.”

Tips from the 2021 competition winners

Preparation. Make sure that you can speak about all aspects of your poster. Practice giving a short presentation and prepare responses for a list of potential questions. Read the relevant literature within your field of study and practice presenting your poster to your mentor, fellow students and any additional faculty who are willing to help.

Talking to the judges. Try to have a professional and comfortable flow through your poster. Following the scientific method throughout your poster allows for your audience to get a clear idea of the thought process behind the work. As you talk, follow your poster as a reference, highlighting significant pieces of data as they come up.

General. Use this as an opportunity to understand your research techniques, learn how to write an abstract, create a fantastic poster and network with other scientists in the conference. The competition is a wonderful opportunity to showcase all the hard work you have done. Be confident and think of it as an opportunity to share ideas with other scientists. No matter the result, you will gain insights you can apply to your own research.

Virtual is possible but lacks pizazz

When the 2021 ASBMB Annual Meeting was held in a virtual format because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Student Chapters Steering Committee provided input on reformatting the poster competition.

Jeremy Johnson, a professor at Butler University and a member of the poster committee, served as a judge.

“I got to experience the virtual poster session from the planning and implementation sides. I had lowered expectations for the virtual poster session, but I was pleasantly surprised,” he said. “For this format, the students prerecorded a shorter overview of their poster and research story, which judges were able to interact with prior to the interpersonal conversation about their poster. This format gave myself as a judge more time to examine the poster, think about the results, and then have a more informed conversation with the students about their results.”

Pamela Mertz is a professor at St. Mary’s College of Maryland and is chair of the ASBMB Student Chapters Steering Committee. She noted that the virtual format benefited undergraduates who in normal years might have faced barriers to travel such as prohibitive expenses or academic scheduling issues.

Joseph Chihade of Carleton College in Minnesota, also a member of the poster competition committee, said that “having to come up with a polished, recorded elevator speech describing the poster helped develop skills that might otherwise not have been honed quite so sharply.”

Still, the people we talked to agreed that there is no substitute for the experience of attending an in-person meeting.

“Going to a big national conference, especially for an undergrad, and being able to network with different types of people and go to different types of sessions in person and seeing all those interactions — I think that’s something you can’t replace and have the same experience with a virtual conference,” Mertz said. “The enthusiasm and the energy in that room when that event is happening is not something you can mimic virtually.”

Chihade added that sometimes it’s hard to get a sense from virtual poster sessions “of the wide scope of work being done by other undergraduates.” He added: “The excitement and buzz of that crowded in-person poster session is just marvelous.”

What sets the ASBMB competition apart

While other scientific societies and organizations hold undergraduate poster competitions, there are some aspects of the ASBMB’s event that make it unique.

Joseph Chihade, a professor at Carleton College in Minnesota and a member of the ASBMB Undergraduate Poster Competition committee, has been bringing his students to the annual meeting since 2005 and has served as a judge several times.

“Since I have worked exclusively at undergraduate-only institutions, every presentation that I have made at a national or international meeting includes, and is usually entirely composed of, work that was done by undergraduates,” Chihade said.

He noted that while other meetings might have poster competitions, he prefers the ASBMB approach, which allows students to present their work first with other undergrads and then later in the exhibition hall with scientists at all career stages.

“The ASBMB structure seemed set up to actually educate students, while also celebrating their research accomplishments,” he said. “The idea of letting students present posters both in an undergraduate-only setting and ‘on the big stage’ in the regular poster session is so obviously the right thing to do. The fact that the undergraduate session occurs first, so that students get practice and receive outside coaching from the poster competition judges before the regular poster session, is also brilliant.”

Another committee member, Jeremy Johnson, a professor at Butler University in Indiana, agreed. He said: “Unlike undergraduate poster sessions at other large conferences, my students come away feeling valued as a scientist from (the ASBMB event). … They are not merely patted on the back and told congratulations for completing a research project, but they are treated like a scientific colleague.”

Kirsten Block, the ASBMB’s director of education, professional development and outreach, said that “the reputation of the competition extends beyond the ASBMB,” so much so that it’s been replicated.

“In fact, it was ASBMB’s competition that served as inspiration when I established a trainee poster competition for my previous organization,” Block said.

All meeting attendees are welcome

The 2022 ASBMB Undergraduate Poster Competition will be held on Saturday, April 2, the first day of the annual meeting. Many of the people we interviewed for this story emphasized that the competition space is open for all meeting attendees to visit and that doing so can be mutually beneficial. Many of the people we interviewed for this story emphasized that the competition space is open for all meeting attendees to visit and that doing so can be mutually beneficial.

“Graduate students and postdocs attending the meeting might have an undergrad who’s worked with them presenting,” Cathy Drennan of MIT said. “If someone’s a postdoc and thinking about applying for a faculty position and considering what a good summer project for an undergraduate would be, they can get a sense of what is possible at institutions of different types.”

Decorated scientists have something to gain as well, the ASBMB’s director of education, professional development and outreach, Kirsten Block, said: “These students are the future of the discipline. They are eager and excited for the opportunity to engage with established scientists about their work and to learn from them. The competition is a chance to help guide these students in their scientific development, and you may even be able to guide them into a future as a graduate student in your department — or your lab.”

Stephanie Paxson was the staff coordinator for the poster competition for several years before joining the society’s publications department in 2021. She emphasized that anybody can stop by.

“Newcomers can expect to see various types of research in biochemistry and molecular biology. They can meet peers with similar interests and also be able to network with grad school programs and companies at our exhibitor tables,” Paxson said. “At ASBMB, we love to see the hard work of undergraduates come to life at this event.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Building a stronger future for research funding

Hear from Eric Gascho of the Coalition for Health Funding about federal public health investments, the value of collaboration and how scientists can help shape the future of research funding.

Fueling healthier aging, connecting metabolism stress and time

Biochemist Melanie McReynolds investigates how metabolism and stress shape the aging process. Her research on NAD+, a molecule central to cellular energy, reveals how maintaining its balance could promote healthier, longer lives.

Mapping proteins, one side chain at a time

Roland Dunbrack Jr. will receive the ASBMB DeLano Award for Computational Biosciences at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

2026 voter guide

Learn about the candidates running for Treasurer-elect, Councilor and Nominating Committee.

Meet the editor-in-chief of ASBMB’s new journal, IBMB

Benjamin Garcia will head ASBMB’s new journal, Insights in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, which will launch in early 2026.

Exploring the link between lipids and longevity

Meng Wang will present her work on metabolism and aging at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10, just outside of Washington, D.C.