Taking a multidisciplinary approach

Celia Schiffer prefers to approach problems from a multidisciplinary viewpoint. She studied physics as an undergraduate at the University of Chicago and then expanded to biophysics — combining biology, chemistry and physics — for her Ph.D. at the University of California, San Francisco.

“Even when I did my Ph.D., … I worked at the interface between doing experimental crystallography and computational molecular dynamics,” she said, “and that continues to this day when I apply biophysics, structural biology and chemistry to elucidating the molecular mechanisms of drug resistance in quickly evolving diseases

For her multidisciplinary work on drug resistance, Schiffer will receive the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2020/2021 William C. Rose Award recognizing contributions to biochemical and molecular biological research and commitment to the training of younger scientists.

Schiffer started the Institute for Drug Resistance in the University of Massachusetts Medical School, which she currently heads. Her lab is known for a culture that enables researchers from diverse backgrounds to pursue their work amicably within the group.

“My lab has gained the reputation for being a friendly, supportive place to learn and do science,” Schiffer said.

She believes being respectful to fellow researchers is the key to a successful lab where science can be pursued without stresses that often selectively affect international students and those from underrepresented minority backgrounds.

Schiffer finds that some students suffer from imposter syndrome — believing they are not as good as their peers — despite what their professors or peers actually think. Exposure to broader scientific platforms, such as attending conferences, helps these students realize their potential, she said.

“I try to encourage my students so that they are able to see how their project fits into the bigger picture.”

Beating drug resistance

Much of Celia Schiffer’s work is on elucidating how mutations in drug targets affect resistance to the drug. Schiffer is interested in the specificity of molecular recognition.

“Drug resistance occurs as a result of evolution,” she said, “when drug pressure changes the balance of molecular recognition events, selectively weakening inhibitor binding by mutation while maintaining the biological function of the therapeutic target.” These changes involve alteration of both the structure and the dynamics of the target.

In her award lecture at the 2020 ASBMB annual meeting, Schiffer will talk about strategies to avoid drug resistance in the drug-design process.

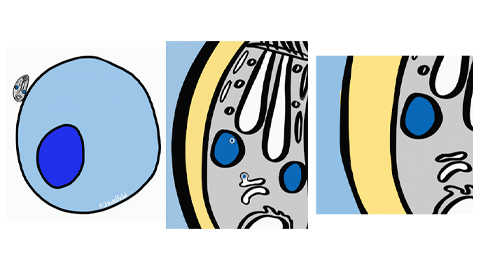

One such strategy arose from her team’s recognition that many resistance mutations occur where the inhibitor protrudes beyond the volume necessary for substrate recognition.

By targeting an inhibitor to the substrate envelope, the probability of resistance can be decreased, as a mutation impacting the inhibitor binding will compromise substrate turnover.

“We discovered and validated this strategy through inhibitor design and testing in several systems,” Schiffer said. These systems include viral proteases in HIV and hepatitis C. The concept is broadly applicable to other quickly evolving diseases such as cancer.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Sketching, scribbling and scicomm

Graduate student Ari Paiz describes how her love of science and art blend to make her an effective science communicator.

Embrace your neurodivergence and flourish in college

This guide offers practical advice on setting yourself up for success — learn how to leverage campus resources, work with professors and embrace your strengths.

Survival tools for a neurodivergent brain in academia

Working in academia is hard, and being neurodivergent makes it harder. Here are a few tools that may help, from a Ph.D. student with ADHD.

Quieting the static: Building inclusive STEM classrooms

Christin Monroe, an assistant professor of chemistry at Landmark College, offers practical tips to help educators make their classrooms more accessible to neurodivergent scientists.

Hidden strengths of an autistic scientist

Navigating the world of scientific research as an autistic scientist comes with unique challenges —microaggressions, communication hurdles and the constant pressure to conform to social norms, postbaccalaureate student Taylor Stolberg writes.

Richard Silverman to speak at ASBMB 2025

Richard Silverman and Melissa Moore are the featured speakers at the ASBMB annual meeting to be held April 12-15 in Chicago.