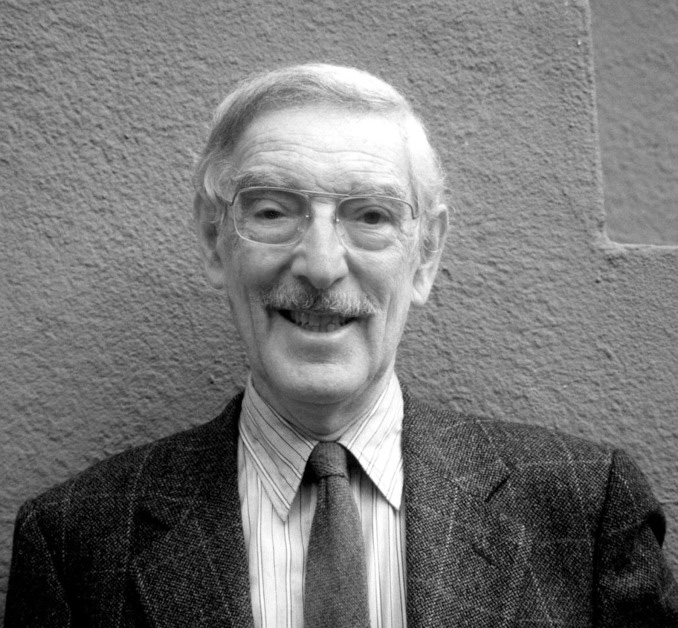

In memoriam: Bruce Ames

Bruce Ames, an emeritus professor at the University of California, Berkeley and a senior scientist at Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute, died Oct. 5. He was a former Journal of Biological Chemistry editorial board member and an American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology member from 1957 to 2010.

In the 1970s, Ames invented a cheap and easy way to assess mutagenicity that helped identify many environmental and industrial carcinogens; it became known as the Ames test.

Lawrence Marnett, a professor and dean emeritus at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, said of the test, “It continues to make an enormous contribution to keeping hazardous chemicals out of the environment, our food chain and pharmaceuticals. It also strengthened our understanding of the linkage between mutations and cancer.”

Ames was born Dec. 16, 1928, in New York City to Maurice and Dorothy (Andres) Ames. Ames attended the Bronx High School of Science and earned an undergraduate degree in chemistry and biochemistry at Cornell University before heading to the California Institute of Technology for graduate studies with Nobel Prize winner Herschel Mitchell. In Mitchell’s lab, Ames identified key steps in the histidine biosynthesis pathway using mutant strains of the fungi Neurospora crassa.

According to F. Peter Guengerich, a professor at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine Basic Sciences, this work set the stage for Ames’ future endeavors.

Ames did postdoctoral work on enzymology in Bernard Horecker's lab at the National Institutes of Health and stayed on as an independent investigator. There, he discovered histidine pathway enzymes and developed Salmonella mutants unable to produce histidine to test for chemical carcinogens. When these mutants are exposed to a suspected mutagen, only those that mutate to restore histidine production grow on histidine-free media, which allowed Ames to quantify relative mutagenesis.

Ames described the NIH in the 1950s as “a wonderful place to do science,” and Guengerich mentioned it in his 2020 retrospective about longtime JBC editor-in-chief Herb Tabor: “In the early days at the NIH, a group of what were to become stellar scientists would meet to eat lunch daily over presentations and lively discussions of current literature in the growing field of biochemistry.”

Ames met and married Giovanna Ferro-Luzzi while he was at the NIH. At the time, she was a postdoc at Johns Hopkins University, and she later moved to the NIH.

Along with Gordon Tomkins, Gary Felsenfeld, Martin Gellert and others, Ames was, in 1962, a founding member of the NIH Laboratory of Molecular Biology. In a 2024 retrospective about Felsenfeld, Gellert and colleagues wrote, “For years the group worked productively as sort of a commune, with each member rotating as laboratory chief for a year, hardly encumbered by any administrative duty.”

In 1967, the Ameses and their children moved to the University of California, Berkeley. There, Bruce Ames further developed his eponymous test by introducing a liver homogenate to simulate metabolic activation. These efforts lead the test to be widely adopted in industrial and regulatory settings. In addition, Ames studied the regulation of the histidine operon by transfer RNAs.

In early 2000, Ames moved his lab to the Children’s Hospital of Oakland Research Institute and continued his work there until he was in his 90s. In Oakland, he examined the effects of vitamins on mitochondrial decay and aging.

Ames received the National Medal of Science in 1998, was an elected member of the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and an American Association for the Advancement of Science fellow. He received many other international honors and awards.

Ames was “one of the smartest and most interesting individuals I have known in science,” Guengerich wrote. “Bruce championed a scientific and logical approach to the understanding and regulation of chemicals in nature and the environment, including the role of nutrition.”

Marnett concurred. “Bruce Ames loved science more than anyone I’ve ever known,” he wrote. “He was clever and innovative with an intense focus on solving significant problems of practical importance.

“Bruce didn’t rest on his laurels,” Marnett wrote. “In any conversation, he would express his opinion that ‘I’m doing the best research of my life.’ We will miss him greatly. He was not only a great scientist but a kind, thoughtful person who was a delight to be with.”

Guengerich concluded, “I always enjoyed my meetings and discussion with him over the years. In 2003, he penned a JBC Reflection, An Enthusiasm for Metabolism (which I recommend reading), and appropriately ended, ‘With so much work to do, I have no plans to retire from science.’”

Ames is survived by his wife, Giovanna Ferro-Luzzi Ames; their children, Sofia and Matteo Ames; and two grandchildren.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

2026 ASBMB election results

Meet the new Council members and Nominating Committee member.

Simcox wins SACNAS mentorship award

She was recognized for her sustained excellence in mentorship and was honored at SACNAS’ 2025 National Conference.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.