Keeping it real

It is easy to be in awe of Carolyn Bertozzi. In 1999, she became a MacArthur fellow for her research in glycobiology. She was just 33. She has been an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute since 2000. She won election to the National Academy of Sciences as well as the National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine). And that’s not all of her scientific awards and honors.

Carolyn Bertozzi uses Twitter to show the realities of life as a scientist.PHOTOCOURTESY OF LINDA A. CICERO FOR STANFORD NEWS SERVICE

Carolyn Bertozzi uses Twitter to show the realities of life as a scientist.PHOTOCOURTESY OF LINDA A. CICERO FOR STANFORD NEWS SERVICE

Bertozzi, an endowed professor at Stanford University, leads a team of more than 30 people whose mission is to use tools of chemistry to study biology and develop new molecules for improving human health. Projects in the lab include the development of mass spectrometric methods to study glycosylated proteins in cells, with particular applications in cancer and stem-cell research, and understanding some of the key enzymes in the bacterium that causes tuberculosis and using the information to create a point-of-care diagnostic device for the disease. Michael Marletta at the University of California, Berkeley, notes that Bertozzi is “just the best” at using a variety of disciplines to “understand complicated biology.”

With all the success that Bertozzi has earned, you might think that she has a golden touch. This is where her Twitter feed comes in.

“It’s good for me to air all the petty humiliations of life” on Twitter, says Bertozzi, which she regularly uses to share science news and aspects of her life to her more than 2,000 followers.

Two years ago, on discovering she couldn’t fly from the U.S. to Canada because she had forgotten her passport at home, Bertozzi delighted her Twitter followers by listing her top 10 travel blunders. (One was forgetting her bag on an airport shuttle, which resulted in a bomb squad being called in.) It prompted one of her followers to quip, “MacArthur geniuses: They’re just like us!”

That’s precisely the point. “I think people feel that scientists are not real people with real lives and real problems that are mundane,” says Bertozzi. “I figured I could dispel that myth on Twitter.”

Bertozzi belongs to a cohort of scientists who now regularly use Facebook and Twitter for the sake of science. A 2015 report, “How scientists engage the public,” from the Pew Research Center, done in collaboration with the American Association for the Advancement of Science, stated that 27 to 47 percent of AAAS members use social media to discuss science or stay abreast of scientific developments. Nearly half of the scientists on social media are looking to attract both specialized and general audiences to their discussions and heighten awareness of the scientific enterprise.

Opening up

Bertozzi wasn’t an early adopter of social media. “I never had a Facebook page. I skipped that entire era apparently,” she says.

The change happened in 2014 when she became editor for a journal, ACS Central Science, which is published by the American Chemical Society. Some of ACS’s employees encouraged Bertozzi to use Twitter to promote the journal.

Initially, Bertozzi was highly skeptical about the value of Twitter. Like other social media platforms, it appeared to revolve around “mostly stupid minutiae,” says Bertozzi.

But she soldiered on and started to follow journals that had Twitter feeds. Then she discovered Berkeley’s feeds. (Bertozzi’s laboratory was based in Berkeley before her move to Stanford in 2015.) The feeds from the different schools on campus helped her plug into various events and research happening on campus.

She soon discovered that a number of universities “have all these interesting Twitter feeds. So I started following Cornell, MIT, Caltech and some Harvard sites,” she says. “Then I discovered there were a bunch of chemists who are tweeting, so I started following them. The funny thing is, within a few months, all of sudden, I was so up on current events.” The same happened with the scientific literature because of all the journal newsfeeds she was following.

As any overscheduled scientist, Bertozzi notes she doesn’t have the time to read news and scientific papers in print or at various websites. However, Bertozzi found she could follow current events in real time on Twitter “when I’m stuck in line at Safeway,” she says. “I can do it when I’m at the airport stuck in line. It’s all on my phone.”

Then, a few months into joining Twitter, came Bertozzi’s social-media breakthrough: “By accident, once or twice, I tweeted something original from my own mind.”

Those tweets ended up getting shared widely and garnered Bertozzi more followers. She realized that the social media platform was a great way to discuss the various issues facing science and scientists. And she could use the social media platform to show that, despite all her success, she is fallible.

Bertozzi has used Twitter to air her biggest peeves about misconceptions of science (“Chemicals=bad, scientists=old white men, chemistry=boring or all done (where is our Breakthrough Prize!”)). She has jumped in on discussions about the purpose of postdoctoral stints (“Postdoc = training/mentored position. Should expect support for job search”). She has given career advice to younger scientists (“Communicate research with story telling skill, understand peoples’ motivations, know audience, think big”).

Bertozzi also uses Twitter to discuss openly the challenges of a full-time job and parenthood. Bertozzi and her wife have three boys, all under age 8. “This whole idea of work–family balance — what could be more of a misnomer for your life than the word ‘balance’?” she says. “It’s a complete joke.”

Bertozzi says she believes younger scientists, especially women, need to see that even the most successful people don’t have their act together at all times. “Women get this weird impression that somehow, you have to be so perfect to be successful,” she says. “That’s not true at all.” (On Twitter, she has dismissed the idea that she is a perfect mother, following up with a few parenting tips including “Eat ice cream before pizza as lesson in how to blunt insulin spike.”)

She recounts a time when she was visiting a university to give a talk and was taken to lunch by some of the graduate students at the university. One of the students couldn’t fathom that Bertozzi changes her children’s diapers. “It’s not like there’s a diaper-changing robot under my bed!” she says. “It’s hard to know where it started, but people think that you’re somehow a different species” when you’re a successful scientist.

‘I can’t believe I let that happen’

Bertozzi doesn’t want to set false standards. It’s not just on Twitter that Bertozzi is willing to reveal her bumps and bruises. On a “ People Behind the Science” podcast that was taped in January, Bertozzi spoke about the mistakes she made when she began setting up a laboratory at Berkeley’s chemistry department as a new assistant professor in 1995. Like many junior faculty members, Bertozzi fumbled. “Someone gives you the keys to the car, but you never really learned how to drive,” Bertozzi said during the podcast. “You have no experience, really, in managing a research enterprise.”

She assumed her first batch of graduate students would be copies of her. “They would have the same commitment to their research, they would have the same ambitions, the same interests,” she said during the podcast. “Of course, no two people are alike, much less five people. I found myself frustrated that they couldn’t read my mind.”

Bertozzi soon learned that she had to communicate her expectations clearly. She had to appreciate that different people had different work styles and motivations and that she had to tailor her mentorship and management to the person.

“I had a lot of work to do on my soft skills early on. I really screwed up a lot of things. I had students leave my lab out of frustration with me,” said Bertozzi in the podcast. “In retrospect, I can’t believe I let that happen.”

But now, Bertozzi excels as a mentor. “You’ll be very hard-pressed to find somebody to say anything bad about Carolyn,” says Christina Woo, who recently completed a postdoctoral stint with Bertozzi and is starting her own laboratory at Harvard University. “She is an especially supportive mentor who really gets how to support her postdocs and students.”

Marletta sounds rueful about Bertozzi’s recent exit from Berkeley. “Carolyn is a fantastic recruiter of students,” he says. “Now that she’s at Stanford, that’s a problem for us here! She has this ability to connect right away. The connection comes from listening to people, seeing what they are like and what they are interested in, and finding a way to intersect with that.”

Bertozzi is known as a masterful communicator.PHOTO COURTESY OF BERTOZZI LAB

Bertozzi is known as a masterful communicator.PHOTO COURTESY OF BERTOZZI LAB

Emotional connection

Marletta and Woo describe Bertozzi as a masterful communicator who knows how to draw in an audience and make them care about what she has to say. She is a consummate storyteller.

Some of her mastery comes from the fact that Bertozzi is a skilled jazz and rock keyboardist who performed in a band in college and seriously contemplated majoring in music. Being a musician has given Bertozzi a taste for the thrill that comes from forming a connection between the person on-stage and the audience. The goal of a lecture, just as in a musical performance, says Bertozzi, is “you’re trying to create an emotion that you share with the audience.”

Every time she gives a lecture that falls flat, Bertozzi does a postmortem. By asking herself where she lost the audience or lost steam with her delivery, she makes sure that she doesn’t repeat those mistakes, and she reviews how she is pacing the narrative. As she puts it, “every lecture you give should have an arc, a story, and it should build up a cathartic moment.”

Woo says that she tries to emulate Bertozzi’s presentation style because “I’ve seen people come from totally different chemistry backgrounds go to her talk and come out like ‘Wow, I actually learned something from that!’”

Bertozzi understands how leaving out information is as important as leaving in information when telling a story. “She’s very much a minimalist when it comes to making slides,” says Peter Robinson, a recent Ph.D. graduate from the lab who now is the chief scientific officer of a startup company called Enable Biosciences. “Even though we publish a lot of papers and have a lot of data, if you go to one of her talks, she might summarize an entire project by showing what that group is trying to achieve in a single well-designed slide.”

The approach Bertozzi takes to make her lectures compelling mirrors the approach she has toward Twitter. She cares about sharing her passion for research and making science accessible to whomever may be interested.

Bertozzi says her colleagues look at her askance when she’s busy taking photos at department functions to tweet. “They laugh at me and think it’s so silly because they think of it as a teenage girl’s pastime, which is probably what I would have thought a couple of years ago,” says Bertozzi. “I feel it’s too bad because we’re doing ourselves a disservice by disdaining a mode of communication that so many millions of people use. What a waste of an opportunity to show people what you do and who you are.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Defining a ‘crucial gatekeeper’ of lipid metabolism

George Carman receives the Herbert Tabor Research Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

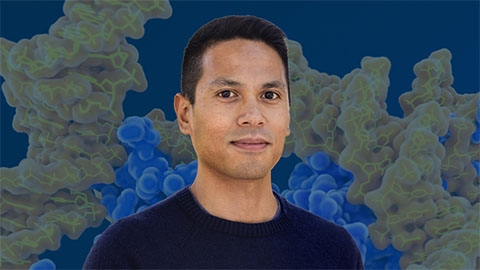

Nuñez receives Vallee Scholar Award

He will receive $400,000 to support his research.

Mydy named Purdue assistant professor

Her lab will focus on protein structure and function, enzyme mechanisms and plant natural product biosynthesis, working to characterize and engineer plant natural products for therapeutic and agricultural applications.

In memoriam: Michael J. Chamberlin

He discovered RNA polymerase and was an ASBMB member for nearly 60 years.

Building the blueprint to block HIV

Wesley Sundquist will present his work on the HIV capsid and revolutionary drug, Lenacapavir, at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, in Maryland.

In memoriam: Alan G. Goodridge

He made pioneering discoveries on lipid metabolism and was an ASBMB member since 1971.