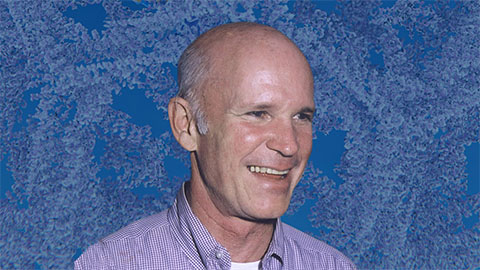

‘Science is everything’

Olaposi Idowu Omotuyi has traveled the world for his education, and he believes in bringing the knowledge he’s gained back to his home country. His focus, for now, is on metabolic and infectious diseases with a special interest in developing plant-based antivirals.

Benin, Nigeria, and then studied pharmaceutical science in Japan before

returning to Nigeria to teach and do research.

Born in Ekiti State, Nigeria, Omotuyi was interested in science from a young age. One of his neighbors was a professor whose children were in training for medical lab science. They discussed their work with Omotuyi, kick-starting his fascination with how the world worked.

“In Africa, everything was voodoo until you understood what exactly what was going on,” he said. “That somebody could sit down and explain to me how the cells work, how tissues work, how organs interconnect into systems — that was fascinating.”

After completing his doctorate in biochemistry from the University of Benin, Nigeria, Omotuyi applied for a Japanese government Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology scholarship in 2009. Through the program, scientists from all over the world conduct research in Japan. After several stages of interviews, Omotuyi was one of five applicants chosen for a position at Nagasaki University to work toward his second doctoral degree in pharmaceutical science.

In Japan, in a first-class laboratory and heavy scientific environment, he saw a sharp contrast between an industrialized country and Nigeria. He said he believes some African scientists might be tempted to stay in a country like Japan to do research, while others want to raise the level of science in Africa by returning to their home country. In the end, he chose to bring his skills back to Nigeria.

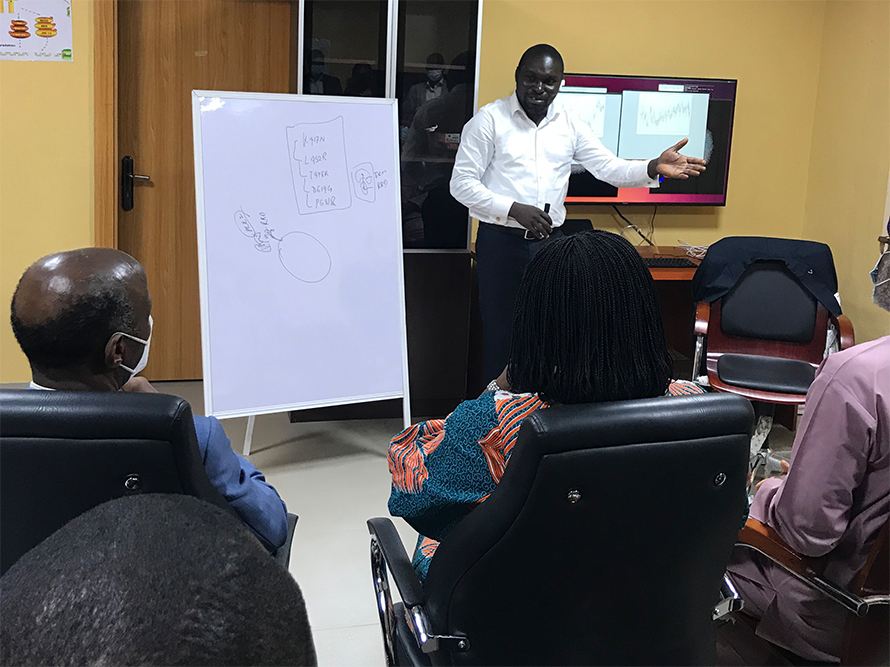

Fund, a tour of the Institute for Drug Research and Development at Afe Babalola

University.

The science was not the only thing that drew Omotuyi back. For him, being a tutor to undergraduate students first at Adekunle Ajasin University in Ondo State and now as a professor at the College of Pharmacy at Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti, is “an absolute joy.”

“Not only being able to teach this experience, this knowledge to young people, but to be able to help them grow scientifically,” Omotuyi said. “I am really impressed at how they receive it.”

Few Nigerian scientists are able to translate their research into a product or policy that then is disseminated to a wide population in their country. Omotuyi said he has been fortunate in his networking and in the subject of his research to receive funding from the Afe Babalola University fund for translational research as well as garnering attention from other institutions for partnerships and funding. His lab now is studying both metabolic diseases and infectious diseases such as Ebola and COVID-19, which attracts government attention and resources.

An herbal drug called virudine developed in Omotuyi’s lab for the treatment of COVID-19 is undergoing independent investigation at the Nigerian Institute for Medical Research, and another repurposed drug for Lassa virus disease developed in partnership with the National Biotechnology Development Agency in Nigeria is being tested for proof-of-concept clinical trials by the NIMR.

Omotuyi teaches his students the importance of patriotism in their work. In countries like the United States, he sees that scientists apply research to their local environments and local problems, and these local solutions are accepted for international application. But African scientists end up doing research that benefits other countries instead of their own.

“African scientists who are exceptional at what they do are easily poachable,” Omotuyi said.

“The first point of science for me is that (my students) should solve local problems — and in solving them they should be innovative.”

Omotuyi said his favorite part of his work is getting to the biochemical details of how novel structures interact with macromolecules like proteins and nucleic acids, both during test tube experiments and in animal research models. But overall, the entire subject of biochemistry is what interests him.

“Science is something for me, like bread and drink, wake, sleep — everything,” he said. “Science, and nothing else.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Redefining excellence to drive equity and innovation

Donita Brady will receive the ASBMB Ruth Kirschstein Award for Maximizing Access in Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

ASBMB names 2026 fellows

The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology announced that it has named 16 members as 2026 fellows of the society.

ASBMB members receive ASM awards

Jennifer Doudna, Michael Ibba and Kim Orth were recognized by the American Society for Microbiology for their achievements in leadership, education and research.

Mining microbes for rare earth solutions

Joseph Cotruvo, Jr., will receive the ASBMB Mildred Cohn Young Investigator Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

McKnight wins Lasker Award

He was honored at a gala in September and received a $250,000 honorarium.

Building a stronger future for research funding

Hear from Eric Gascho of the Coalition for Health Funding about federal public health investments, the value of collaboration and how scientists can help shape the future of research funding.