Living through art and science

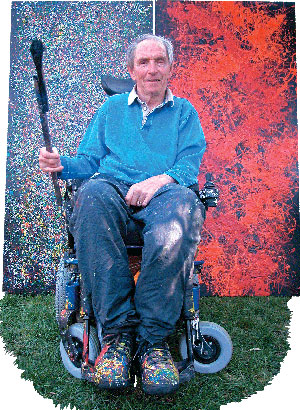

Robert Schimke has ditched the pipettes and gels for paintbrushes and canvases. An emeritus professor from Stanford University’s department of biological sciences, Schimke’s scientific portfolio is tremendous.

From the 1960s to the 1990s, his laboratory made major contributions to at least four different areas of biology. Schimke served on boards for scientific journals and biotechnology companies and was president of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology in 1988. But now he has left science behind to spend his time creating art. He also spends his days in a wheelchair.

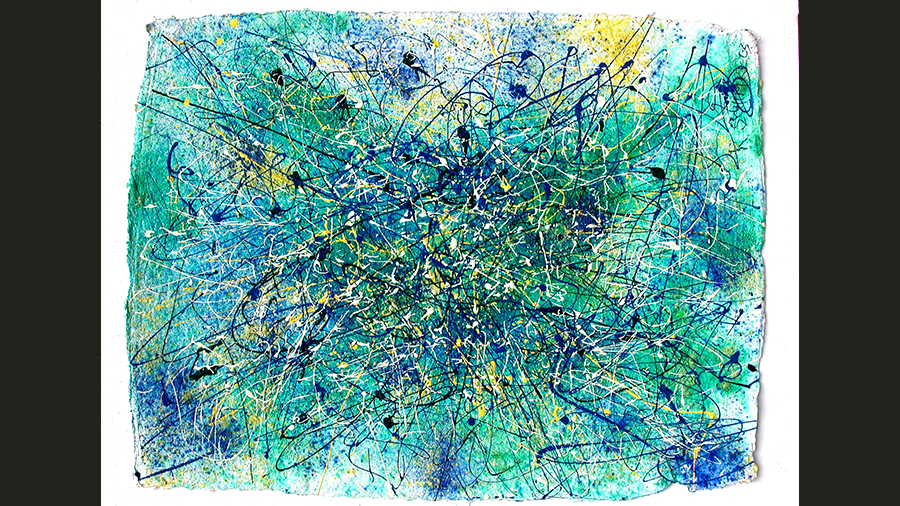

A quadriplegic for 17 years with limited use of his arms and feet, Schimke has found a way to express movement through art. “I used to be rather physically active. Obviously I can’t do that anymore so I take it out on my paintings!” he says. “They are all moving. There’s nothing static about them.”

Schimke was ready to leave science even before the accident that left him mostly paralyzed. “I was 62 at that time and I was ready to retire, which is very different from most scientists. They don’t know what else to do. I really wanted to retire so that I could paint and garden,” says Schimke.

Schimke hasn’t let the accident dash his dreams of painting. These days, he melds his scientific methods with his artistic skills to get different kinds of paint to sweep, skirt, splotch or splatter over canvases. “I’m continually experimenting with new techniques. Many artists over time will paint more or less in the same genre that they’ve painted all the time,” he says. “I try all kinds of different things.”

Schimke is focused these days on understanding what happens to latex paints, which he purchases from Home Deport, as he drips and splashes them across canvases. “I’m trying to figure out how to make some interesting shapes by simply pouring dilute, light-colored paint on canvases that are painted black,” he says. “The other thing I have been doing very recently is to make relatively small canvases that have drips of undiluted paint that comes right out of the gallon can. That produces some striking three-dimensional patterns. They have a lot of different colors … I must say if you look at them, all you can do is smile.”

Early years

There weren’t many smiles when Schimke was growing up in Spokane, Wash. Born in 1932, “my first eight years were right in the middle of the Depression,” he says. “I really didn’t have a lot of the fancy accoutrements that all kids have these days.”

His father was a dentist and his mother was a homemaker. “They had their own problems,” reflects Schimke. “I didn’t have too happy a childhood.”

A self-described loner, Schimke was most content riding his sister’s bicycle (hers was superior to his) around the forests on the outskirts of Spokane and spending Friday afternoons at his grade school when they held art classes. “I loved to paint and muck around with it,” he says, recalling when he tried to paint daffodils with oil paints and failed. No one around him, however, was an artist, and he didn’t have anyone encouraging him to pursue art. At high school, he abandoned his artistic pursuits.

For his undergraduate degree, Schimke went to Stanford University, where he ended up in the premed program and got married. “My wife was majoring in humanities. One of her courses was on art history,” says Schimke. “I learned more about art history than probably anything else at Stanford!”

After getting his undergraduate degree in 1954, Schimke and his wife went hitchhiking in Europe. “We went to all the art galleries,” says Schimke. “We didn’t go to Spain and Russia, but we saw literally everything else that we possibly could. That was a lot of fun.”

After he returned, Schimke went on to get his medical degree in 1958 from Stanford. He interned at the Massachusetts General Hospital until 1960 and then was drafted into the Public Health Service. The draft got him into the National Institute of Arthritis and Metabolic Diseases, where he worked with Herb Tabor, who later became editor-in-chief for the Journal of Biological Chemistry. In 1966, Schimke returned to Stanford as a faculty member.

Over the years, Schimke’s group made significant contributions to understanding protein turnover, steroid hormone control of gene expression, the connections between cell division and apoptosis, and gene amplification as a way for cells to resist cancer chemotherapy drugs. Schimke’s work on protein turnover and gene amplification was featured as a JBC Classic (1). His work on gene amplification is now used for mass production of large quantities of therapeutic proteins, such as erythropoietin and tissue plasminogen activator, in mammalian cells.

Schimke also was a scientific adviser to Monsanto, DuPont and Amgen and was crucial in helping Amgen launch its first blockbuster drug, Epogen, a version of erythropoietin. Schimke was a JBC associate editor from 1975 to 1981 and from 1983 to 2002 and also served on its editorial board. In addition to numerous awards, he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1976 and to the Institute of Medicine in 1983.

The first bursts of serious painting

But as life went on, tragedies struck. At those times of suffering, Schimke found himself turning to his boyhood passion of painting. His wife Mary died suddenly of cerebral hemorrhage in 1976. After her death, "I decided I didn't want to do science," he said.

One day, while in England, where he had gone to do a sabbatical, Schimke walked down to a Camden Town flea market. There he discovered a set of pastels priced at 50 pence, “undoubtedly stolen from somewhere.” With these pastels in his hands, he felt he ought to do something with them. So he bought some good-quality paper and began to ease back into art.

When it came time for him to return to the U.S., Schimke realized the pastels were powdery and would brush off during the course of the journey. At this point, he decided to switch to oil paints because they lasted better and also because he had always loved to use them. He worked with oil paints for a while back in the U.S., but his laboratory got involved in work that would lead to the discovery of gene amplification. “That was something that brought me back into science in a big way,” he says. He returned to the laboratory in 1977.

In the mid-1980s, he experienced another artistic burst and left the laboratory. This time, he focused on placing natural products, such as eucalyptus and bamboo, on canvas so that their three dimensional shapes played with light and shadow.

But then his research group got involved in studying how mistakes in regulating the cell cycle caused gene amplification or cell death. Schimke returned to the laboratory to devote his time to the research.

The accident

In February 1995, on a Saturday afternoon, Schimke mounted his bike to cycle back home from the lab. Palo Alto, where Stanford University is, has mountains on its borders that reach up at least 3,000 feet, and Schimke often biked them. That day, he decided to go up halfway and take the long way home.Around 2 p.m., Schimke was in a bike lane on Sand Hill Road in Woodside, a small town filled with redwood, oak and eucalyptus trees. The road had a T-intersection. “I was going to go straight in the T, but some bicyclists in front of me were going very slowly and were turning right,” says Schimke. “There was a car behind me whose driver thought I was part of that group and was going to turn as well. She started to make a turn, and her tire hit me.”

Schimke has a few hazy memories of the next few moments. “I remember vaguely, very vaguely, somebody talking to me and putting me on a stretcher. The next thing I remember was the doors to the emergency ward at Stanford University opening up,” he says. “The next thing I remember somebody saying, ‘Do you know somebody to call?’” Schimke was aware enough to tell them to call his current wife, Patricia Jones, Stanford’s vice provost for faculty development and diversity.

Schimke stayed at the local county hospital for three days. Because he had served in the Public Health Service, he was considered a veteran. With Tabor’s contacts at the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, Jones got the necessary paperwork to have Schimke quickly transferred to the Palo Alto veteran’s hospital, which had a better spinal cord injury center.

In the second week after the accident, as a slow recovery loomed, Schimke says, “I remember thinking, ‘All right, Bob, what the hell are you going to do now? You better start doing something!’ I was determined I was going to get better.”

The accident left Schimke’s spinal cord damaged but not completely severed, so he has some sensory and motor capabilities in his arms and feet. “My hands are like claws. I can grab a pencil and write my name badly,” he says. “I can hold a brush.”

Having fun

On his property in Palo Alto, which is almost an acre in size, Schimke does his art in a garage that has been converted into a gallery. He also makes beaded necklaces. The place is filled with his work, which includes drip paintings in the style of Jackson Pollock and a series done with masks mounted on foam boards. “I’ve painted over 400 different things in my lifetime,” says Schimke. Some of his work is on display at ASBMB headquarters in Rockville, Md.

Schimke says the artists he admires are Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso and, up to a point, Pollock. “Other than the drip paintings that he did, [Pollock] was not a very good artist,” he says. “If Jackson Pollock’s paintings are worth millions and millions of dollars, hell, I can do that stuff just as well as he could. Indeed, I can.”

An assistant helps him open up paint cans, stretch out canvases and clean up. Because of his limited movement, Schimke works on canvases stretched out on plywood and no more than four feet wide. He attaches sticks, the kind used to mix paint, to his paintbrushes so he can reach two feet across the canvas. Then he wheels himself around to the other side to get the remaining two feet. At noon sharp each day, a shrill, 19-year-old Siamese cat makes Schimke stop his work because it insists on having its lunch of turkey breast. “It eats basically what I have for lunch,” chuckles Schimke.

Despite all he has accomplished as a scientist, Schimke says he doesn’t miss science. He tried to stay in touch with his areas of expertise after his accident by continuing to serve as a JBC associate editor, but “it became obvious that I was not keeping up,” he says. “I resigned.”

He is not sure what kind of artist he would have been had the accident not happened. But he is sure of one thing: The art he would have produced would not have been “nearly as interesting and as much fun!”

References

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

2026 ASBMB election results

Meet the new Council members and Nominating Committee member.

Simcox wins SACNAS mentorship award

She was recognized for her sustained excellence in mentorship and was honored at SACNAS’ 2025 National Conference.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.