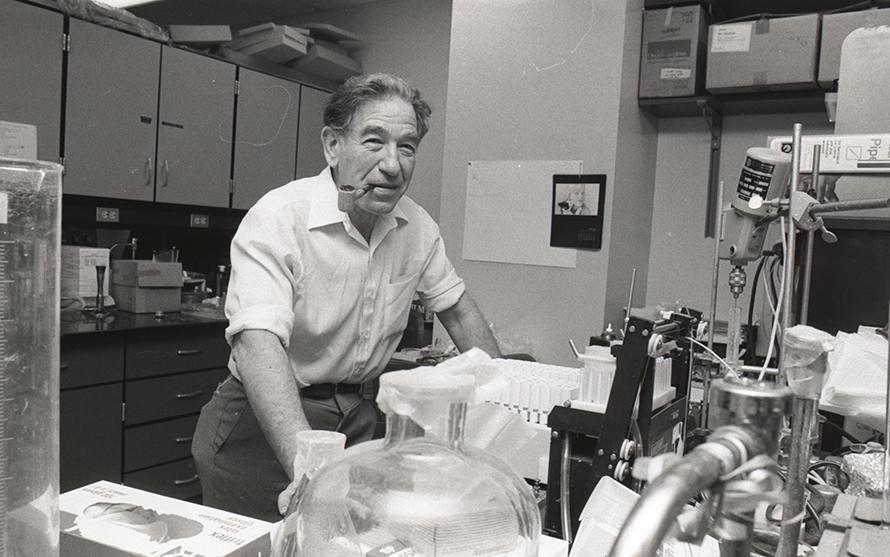

Stanley Cohen (1922 – 2020)

Stanley Cohen was born Nov. 17, 1922, in Brooklyn, New York, and died Feb. 5, 2020, at the age of 97 in Nashville, Tennessee. He was co-recipient, with Rita Levi–Montalcini, of the 1986 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for the discovery of growth factors.

Stanley discovered epidermal growth factor, or EGF, and its receptor. Nearly every biochemistry and cell biology textbook includes at least one section or chapter devoted to the cell signal transduction pathways that subsequently were linked to EGF and receptor tyrosine kinases. His pioneering work has allowed generations of biochemists to study the elegant yet complex pathways that allow cells to respond to external events.

Stanley began his studies at Brooklyn College, where he completed majors in both chemistry and zoology in 1943. He then earned an M.A. in zoology from Oberlin College in 1945. His time dissecting earthworms at Oberlin in Robert McEwen’s class helped to define his later interests. A lab exam at Oberlin asked what cells in the worm performed a function similar to mammalian liver; Stanley did not know the answer. McEwen indicated it was the cells surrounding the intestine. This idea was to influence Stanley’s doctoral work greatly.

He moved to the University of Michigan to begin his Ph.D. at a time when almost everyone was working on nutrition. As he described it, the standard approach was to “find an amino acid or nucleic acid, feed it to a rat or rabbit, analyze its urine.” Stanley decided that instead of nutrition, he wanted to determine whether the cells in earthworms actually did function like a liver. His adviser, Howard Lewis, gave him six months to get preliminary results.

Out on the campus green wearing a miner’s headlight, Stanley collected earthworms. He kept the worms in starving conditions (no dirt or foliage) for about a month. Over that time, he would wash the worms and analyze the contents of the wash. He reasoned that the liverlike chloragogen cells should be able to make urea under those conditions and that he could measure urea in a diffusion assay with urease. Using this approach, he saw increasing amounts of urea produced over time. The longer a worm fasted, the more urea it produced. Stanley then assayed arginase activity in the worm by dissecting the cells around the intestine, adding arginine to the isolated tissue and then measuring urea production. By this method, he noted induction of arginase over time — though at that time, induction of enzymes was not understood at all. The study was published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry in 1950. The moral of the story was, as Stanley would say, “Find something that interests you and do it; you never know what will end up being important.” This was a guiding principle to him as a scientist.

After completing his Ph.D. in 1948 and then working as an instructor in the departments of biochemistry and pediatrics at the University of Colorado, he joined Martin Kamen’s group at Washington University in St. Louis as a postdoctoral fellow to learn about use of radioisotopes in biomedical research. (Kamen had moved to Washington University after being fired from the University of California for talking to the Russian ambassador about using radioisotopes to cure the ambassador’s daughter, who had leukemia.) After his American Cancer Society fellowship ended, Stanley moved to the lab of Viktor Hamburger and Rita Levi–Montalcini. There he began isolating a factor that caused nerve growth. Stanley wrote a retrospective of this work for a special Reflections article in JBC in 2008 — highly recommended reading.

Along with his discoveries at the bench, Stanley was in a journal clubthat included Arthur Kornberg, Martin Kamen, Paul Berg and other faculty, which he referred to as “the best education I ever had.” The journal club’s daily meetings were a time for deep debate and discussion with lots of questions. Stanley presented papers almost every week to the group. He, Kornberg and Berg all went on to win Nobel Prizes (separately). They did not always reach consensus on what constituted the best science. Stanley remembered the day James Watson and Francis Crick’s double helix paper was published in the journal Nature,and they discussed it in journal club. Some in the group thought it was genius; others thought it was just “paper chemistry,” he said. For Stanley, these discussions demonstrated that if you thought something was important, you should follow it up — even when others may not think the results were worth pursuing.

One of Stanley’s most celebrated aha! moments came during studies of snake venom induction of nerve growth. He reasoned that snake venom was made by the salivary gland, so perhaps the mammalian salivary gland had nerve growth factor as well. When the extracts were applied to mouse nerve cultures, there was nerve growth. Also, when the extracts were injected into newborn mice, there was nerve growth and, remarkably, early eye opening. Even decades after the observation, Stanley would recount the moment joyfully: “I was looking at the mice, and they were looking back at me. They weren’t supposed to be doing that!” He later said it was pure luck that he isolated the salivary gland of a male mouse (as it turned out, male mice have significantly higher levels of EGF in the salivary gland than female).

When Stanley moved to Vanderbilt University in 1959 as an assistant professor, he began isolating the factor that caused this early eye opening (as well as early tooth eruption), now known as EGF. Stanley once told me, with a smile, that a colleague tried to talk him out of studying the eye-opening phenomenon — thankfully, he didn’t listen. Stanley applied for support from what then was known as the Human Health and Development Division of the National Institutes of Health. His was the seventh grant funded by the division. His three-page grant application, simply titled “Epidermal growth factor,” supported his work for 38 years, until his retirement in 2000.

Stanley thrived on seeing the details — the little curiosities. One curiosity he never solved, and it clearly baffled him well into retirement, was something he saw when his lab was isolating EGF from mouse submaxillary gland. They used a precipitation test in capillary tubes to track the purification at each step. He made a highly reproducible, and highly unusual, observation: Common house ants coming into his lab overnight from outdoors seemed to be very attracted to the capillary tubes containing extracts from adult male mouse salivary gland but not to the extracts made from female mouse salivary gland. During my postdoc days with him in 1998, he still had a Styrofoam tray with a row of capillaries in his lab that he had moved with him from his old building. The liquid inside had long since desiccated, but the tray and tubes represented a problem he hadn’t solved.

In his later years, Stanley was fascinated by neuroscience and strongly believed that was where the next great biomedical discoveries would be made. He used to say, “You need a 21st century brain to do this work.”

Stanley was always interested in talking science with other scientists; throughout his career, he regularly attended seminars, had impromptu conversations with colleagues in the halls and encouraged others in their work.

He said four things drove him as a scientist:

- Love of learning.

- Interacting with smart people.

- Not being afraid to ask questions.

- Doing what was interesting.

Stanley absolutely loved science, had a curious mind and never took an observation for granted (“Oh, isn’t that interesting?” he would say). He frequently reacted to an experimental outcome with the expression, “It worked — a minor miracle.” Even after earning the Nobel Prize, Stanley maintained a small research group of no more than one or two postdocs at a time and a technician because he wanted to be close to the data and results.

Stanley was not one to sit idle, either at work or at play. He learned to play the clarinet while at Washington University. In those days, there were no column fraction collectors, so on the many late nights he was isolating nerve growth factor, he practiced his clarinet between collecting fractions. He even played in quartets with other scientists (and noted that Kamen was a violin prodigy).

Stanley was an avid double tennis player — very competitive on the court despite leg mobility issues from a bout with polio as a child. He loved to go jeeping and frequented Jeep Jamborees in his black Jeep with an “If you can read this, flip me over” sticker.

Marlene Jayne, longtime department administrator in the biochemistry department at Vanderbilt and Stanley’s close personal friend, would joke that he had a problem quitting smoking. He was known for walking the halls (thinking about science, he said) with his pipe in his mouth. The dean of the medical school wrote him a letter reminding him of the smoking policy. Stan immediately returned the letter stating that he was not smoking but only used the pipe as a pacifier. The dean wrote back congratulating him and pasted a gold star on the letter; Stanley then ditched his pacifier. After Stanley won the Nobel Prize, the chancellor gave him a specially marked parking place close to his office that was his until he retired.

Stanley left a legacy of discoveries that gave us a leap forward in understanding cell signaling, cancer and disease targets. And he had many friends, to boot; his unpretentious style and reassuring smile will be greatly missed.

Stanley is survived by his wife, Jan, and three children and two grandchildren.

Special thanks to Marlene Jayne for photographs and for careful reading of this retrospective.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Sketching, scribbling and scicomm

Graduate student Ari Paiz describes how her love of science and art blend to make her an effective science communicator.

Embrace your neurodivergence and flourish in college

This guide offers practical advice on setting yourself up for success — learn how to leverage campus resources, work with professors and embrace your strengths.

Survival tools for a neurodivergent brain in academia

Working in academia is hard, and being neurodivergent makes it harder. Here are a few tools that may help, from a Ph.D. student with ADHD.

Quieting the static: Building inclusive STEM classrooms

Christin Monroe, an assistant professor of chemistry at Landmark College, offers practical tips to help educators make their classrooms more accessible to neurodivergent scientists.

Hidden strengths of an autistic scientist

Navigating the world of scientific research as an autistic scientist comes with unique challenges —microaggressions, communication hurdles and the constant pressure to conform to social norms, postbaccalaureate student Taylor Stolberg writes.

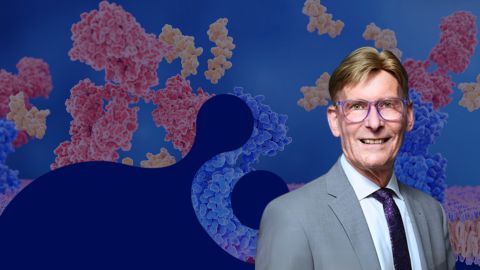

Richard Silverman to speak at ASBMB 2025

Richard Silverman and Melissa Moore are the featured speakers at the ASBMB annual meeting to be held April 12-15 in Chicago.