Tabor award for bacterial colony work

Why can a bacterium usually found in the mouth also drive an infection linked to heart failure? How does a nascent bacterial colony in the heart protect itself from being swept away? Catherine Back won a 2018 Journal of Biological Chemistry/Herbert Tabor Young Investigator Award for her work on the mechanism of adhesion between a bacterial fibril protein and human tissues.

Catherine Back found a novel mechanism for streptococcal adhesion to fibronectin. Courtesy of Catherine Back

Catherine Back found a novel mechanism for streptococcal adhesion to fibronectin. Courtesy of Catherine Back

The protein, which she characterized while she was a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Bristol, helps the oral bacterial species Streptococcus gordonii attach to and colonize human tissues and may contribute to bacterial infection of the heart.

Back’s first research experience was as an undergraduate at Bristol, where she worked with microbiologist Howard Jenkinson on an interaction between S. gordonii and another species of commensal oral bacteria. She stayed on at Bristol for her Ph.D., extending her undergraduate studies with a closer and more multidisciplinary look at CshA, an adhesion protein.

“I thought it was really interesting to work on a protein that not much was known about,” she said.

While Jenkinson remained her primary supervisor, for her project, Back drew on the expertise of three principal investigators from two departments. Jenkinson and Angela Nobbs were frequent collaborators on microbiology research in the dental school, while biochemist Paul Race contributed expertise in protein characterization.

“I managed to work in both departments, learning microbiology and also structural biology,” Back explained. The collaboration between the groups continues to this day. The labs now work together to characterize other bacterial adhesins.

After earning her Ph.D., Back stayed on in Bristol to finish the work described in her JBC article and then moved to the nearby University of Bath to study a new type of vaccine for tuberculosis.

Back grew up in Exeter in Devon, England, and said she enjoys getting outdoors both in Bristol and on visits home. “I often go back to my parents’ house in Exeter,” she said. “It’s near the sea, and near Dartmoor, which is a really nice place to go hiking.”

Back recently returned to Bristol to join the lab of Paul Race for a new project, studying antimicrobials from bacteria that colonize deep-sea sponges.

Catching fibronectin to clamp on tightly

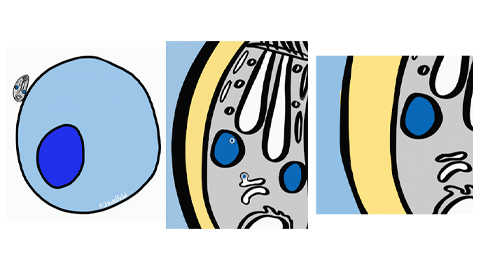

Adhesion proteins are key drivers of bacterial colony formation. In the case of S. gordonii, the protein CshA contributes to binding to the human extracellular glycoprotein fibronectin.

Because S. gordonii can enter the bloodstream and adhere to heart valves, the binding mechanism may have implications for development of heart infections.

Catherine Back and colleagues at the University of Bristol divided a relatively uncharacterized region of the protein into three domains through bioinformatic analyses, publishing their work in JBC in December 2016.

They analyzed each domain’s interaction with fibronectin, finding that one of the three domains did not interact. Of the remaining two, dubbed NR1 and NR2, the on and off rates for NR1 were faster, although NR2 was capable of higher affinity binding. They analyzed the structure of both domains, determining that both are responsible for fibronectin binding. The disordered NR1 domain interacts transiently with fibronectin, the so-called catch. After NR1 makes initial contact, NR2 binds more tightly — the clamp.

Back suspects the binding she described may be relevant to other pathogens. A number of other streptococci “have CshA-like proteins, which have a similar sequence and may have a similar mechanism of interaction,” she said.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Sketching, scribbling and scicomm

Graduate student Ari Paiz describes how her love of science and art blend to make her an effective science communicator.

Embrace your neurodivergence and flourish in college

This guide offers practical advice on setting yourself up for success — learn how to leverage campus resources, work with professors and embrace your strengths.

Survival tools for a neurodivergent brain in academia

Working in academia is hard, and being neurodivergent makes it harder. Here are a few tools that may help, from a Ph.D. student with ADHD.

Quieting the static: Building inclusive STEM classrooms

Christin Monroe, an assistant professor of chemistry at Landmark College, offers practical tips to help educators make their classrooms more accessible to neurodivergent scientists.

Hidden strengths of an autistic scientist

Navigating the world of scientific research as an autistic scientist comes with unique challenges —microaggressions, communication hurdles and the constant pressure to conform to social norms, postbaccalaureate student Taylor Stolberg writes.

Richard Silverman to speak at ASBMB 2025

Richard Silverman and Melissa Moore are the featured speakers at the ASBMB annual meeting to be held April 12-15 in Chicago.