Glycobiology awards; honors for Hall; remembering Saffran, Kornberg, Herrmann

Society for Glycobiology presents awards

Gerald Hart, Robert J. Linhardt and Manfred Wuhrer were among the researchers recently honored by the Society for Glycobiology.

Hart is president of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and a Georgia Research Alliance eminent scholar at the University of Georgia. He received the President’s Innovator Award, given each year since 2015, which honors the contributions of one scientist who has had a significant impact.

For Hart, that impact was not only creating a new field in glycobiology, the dynamic and inducible modification of nuclear and cytosolic proteins via O-GlcNAc, but also shepherding its growth and providing “exemplary service to the glycobiology and life science community,” the society’s website states.

Linhardt, a professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, was honored with the Karl Meyer Lectureship Award. Established in 1990, the award is given to well-established scientists who have made widely recognized contributions to the field of glycobiology.

Linhardt has improved researchers' understanding of glycosaminoglycans and heparins. He was a co-discoverer of polyanhydrides for drug delivery, which resulted in a wafer to treat brain cancer, and he also helped introduce low-molecular-weight heparins into the market.

Wuhrer, head of the Center for Proteomics and Metabolomics at Leiden University Medical Center in the Netherlands, received the Molecular & Cellular Proteomics/ASBMB Lectureship Award. Established in 2013, the award honors scientists who have been at the forefront of the emerging field of glycomics and glycoproteomics.

Wuhrer’s recent research has focused on analyzing the glycans of human proteins, with particular attention to immunoglobulins. His work on technology centers around higher throughput mass spectrometry glycomics workflows, which his lab applies to unravel protein glycosylation signatures of various human diseases including autoimmune diseases, infectious diseases, metabolic disorders and cancer.

Also honored were Nancy Dahms, who received the Rosalind Kornfeld Award for Lifetime Achievement in Glycobiology (reported last month in ASBMB Today), and Jochen Zimmer, who received the Oxford University Press Glycobiology Significant Achievement Award.

These awards were presented at the Society for Glycobiology’s annual meeting November in Phoenix.

Honors for Hall and research partner

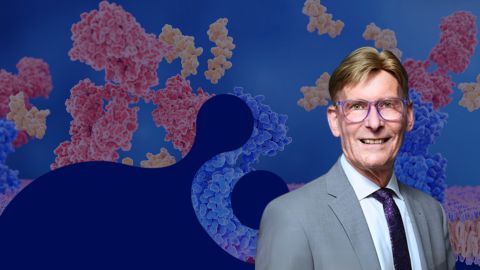

Biochemist Michael Hall has won two awards with David Sabatini for their roles in the discovery of mTOR, the mammalian target of rapamycin: the BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge award in Biology and Biomedicine and the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences’ Sjöberg Prize.

Hall, a professor of biochemistry in the Biozentrum Center for Molecular Life Sciences at the University of Basel, Switzerland, discovered the target of rapamycin in yeast in 1991. Several years later, Sabatini, then a graduate student, discovered its mammalian homolog.

“In simple terms, mTOR is what makes us grow when we eat,” Hall explained when he received the BBVA award.

Before Hall's lab demonstrated that yeast’s TOR complexes link nutrient availability to protein translation and the growth phase of the cell cycle, researchers did not know that growth was actively regulated. Later work from the lab linked mTOR activity to nucleotide synthesis and cytoskeletal organization.

This stronger understanding of mTOR signaling has had clinical implications. The kinase is overactivated in many cancers and has been linked to diseases such as diabetes. Rapamycin, the original mTOR inhibitor, is used as an anti-cancer agent, an immunosuppressant for organ transplantation and a coating for coronary stents to block new growth. Researchers believe reduced mTOR signaling is involved in the longer lifespans of mice fed restricted diets, leading to hopes that mTOR inhibitors might limit the effects of aging-related diseases.

Hall and Sabatini received the Frontiers of Knowledge award in January. Sponsored by the financial group BBVA with selection assistance from the Spanish National Research Council, the award includes a commemorative sculpture and a €400,000 cash prize split among the winners in each category. The Sjöberg Prize, awarded in early February, consists of $1 million, divided between the awardees. Hall was received a Lasker Award in 2017. Sabatini won the ASBMB's Earl and Thressa Stadtman Award in 2012.

In memoriam: Judith Saffran

Judith Saffran, a cancer researcher and a quiet pioneer in women’s postgraduate education, died Jan. 14 in Queens, N.Y. She was 96.

Born Judith Cohen in Montreal in 1923, she attended McGill University, earning a bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1944 and a Ph.D. in biochemistry in 1948. She married Murray Saffran, a fellow McGill student, in 1947 and did postdoctoral research at Montreal’s Jewish General Hospital. She taught an advanced biochemistry lab class at McGill for several years.

The Saffrans moved to the U.S. in 1969 and settled in Ohio, where Judith worked as a researcher first at Toledo Hospital and later at what was then the Medical College of Ohio (now the University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences). Murray founded the department of biochemistry at the college and was a pioneer in the research of stress hormones. He died in 2004.

Judith Saffran and her colleagues examined the binding and metabolic activity of the hormone progesterone, which is crucial to a wide array of biological activity such as neuronal development, steroid production and breast development. It its synthetic forms, progesterone is prescribed as birth control and as menopausal hormonal therapy and gender-affirming therapy. It is also involved in the pathophysiology of breast cancer. To help elucidate this function, Saffran investigated the hormone’s activity in cultures of uterine cells derived from rats and guinea pigs. She also explored the regulatory effect of hormone on the production of other endogenous steroids. She retired from the Medical College of Ohio in 1997.

Saffran, who was descended from a Russian Jewish family, volunteered in the 1990s with the Toledo chapter of ORT, an international charity founded in 19th century Russia that describes itself as a “global educational network driven by Jewish values.” She moved to New York in 2014 to be closer to her daughter, who was then a professor of biochemistry at Queens College.

Few women of Saffran’s generation had doctoral degrees. “She was a pioneer in women's higher education and in women's work as scientists,” her son David Saffran told the Toledo Blade. “She was also humble. She never thought she was special, and she never bragged about her education and her status as a scientist.”

Saffran is survived by her daughter, Wilma Saffran; sons, David, Arthur, and Richard Saffran; nine grandchildren; and five great-grandchildren.

In memoriam: Hans Kornberg

Boston University biochemist Sir Hans Kornberg died Dec. 16. He was 91.

Born in 1928 to a Jewish family in Germany, Kornberg fled to the United Kingdom in 1939, staying with an uncle in Yorkshire. After finishing grammar school, he gravitated toward chemistry and became a junior laboratory technician for Hans Krebs, who discovered the eponymous metabolic cycle, at the University of Sheffield. Kornberg worked in Krebs’ lab through his time at the university, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1949 and a Ph.D. in biochemistry in 1953.

After postdoctoral stints in the U.S. and U.K. and lecturing at the University of Oxford at Krebs’ behest, Kornberg was appointed as the first chair in biochemistry at the University of Leicester in 1960. He moved to the University of Cambridge in 1975, where he was appointed the Sir William Dunn chair of biochemistry. He also served as the master of Christ’s College, then deputy vice chancellor, until his mandatory retirement in 1995. He then took a job at Boston University, where he continued his research and taught upper-level biochemistry.

Kornberg’s seven-decade research career focused on the regulation of carbohydrate transport in microorganisms. He authored more than 250 papers and notably elucidated the glyoxylate cycle, which is used by plants and other nonanimals to enable the biosynthesis of biomass from 2-carbon compounds, as well as the concept of anaplerosis, an important mechanism for ensuring carbon oxidation by the Krebs cycle.

He was made a fellow of the Royal Society in 1965 and knighted in 1978. He was a fellow of the American Academy of Microbiology and a foreign associate member of the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Science.

Kornberg met Monica King at Oxford; they married in 1956 and had four children. King died in 1989 and Kornberg remarried in 1991; his wedding with Donna Haber was the first Jewish wedding to take place on the Cambridge campus. He is survived by Haber; his daughters, Julia and Rachel; his twin sons, Jonathan and Simon; grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

In memoriam: Robert L. Herrmann

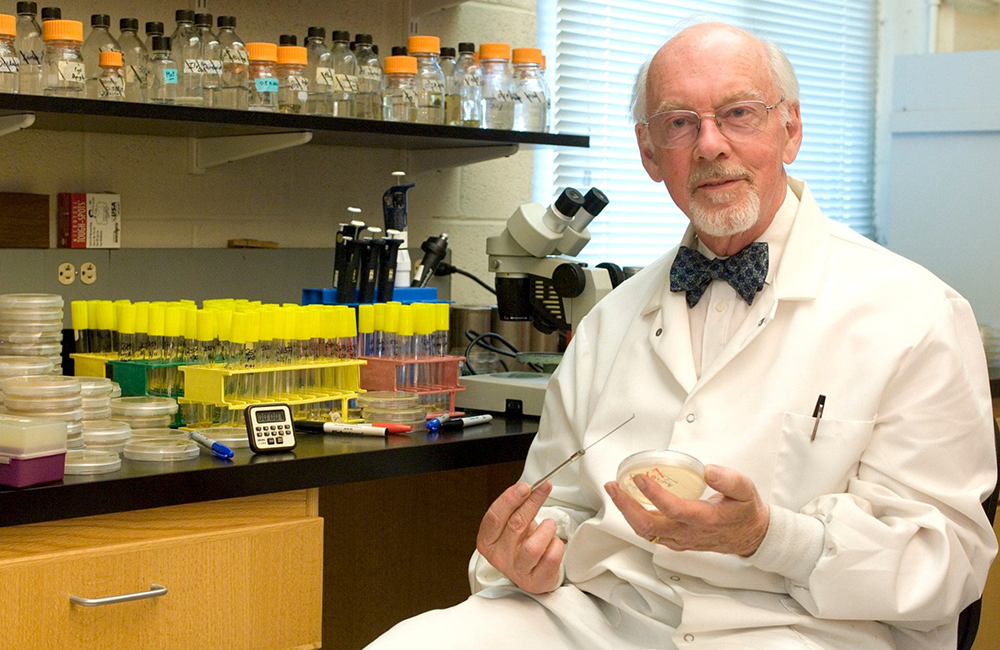

Biochemist Robert L. Herrmann died Dec. 12 at the age of 91.

Herrmann was born in 1928 in New York City and grew up in Queens. His pursuit of an undergraduate degree in chemistry at Purdue University was interrupted by two years of service in the Navy on the U.S.S. Shenandoah, after which he married his childhood sweetheart, Betty Ann Cook. He then returned to Purdue, finished his degree and enrolled as a graduate student at Michigan State University. In 1956, he accepted a Damon Runyon Fellowship at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

In 1957, Herrmann joined the American Scientific Affiliation, or ASA, a Christian religious organization of scientists, and remained active in the group for many decades. There, he met the investor and philanthropist Sir John Templeton, with whom he collaborated in writing several books, including Templeton’s biography. Herrmann was a founding member of the John Templeton Foundation, which supports research at the intersection of science and religion.

After completing his postdoctoral fellowship, Herrmann took a faculty position at Boston University, where he taught biochemistry for 17 years. After a stint teaching biochemistry at Oral Roberts University in Tulsa, Herrmann moved back to New England in 1981 to serve as executive director of the ASA, a position he held until his retirement in 1994.

Herrmann is survived by his wife, Elizabeth Herrmann; sister; Carol; children, Stephen, Karen, Holly and Anders; and eight grandchildren.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Embrace your neurodivergence and flourish in college

This guide offers practical advice on setting yourself up for success — learn how to leverage campus resources, work with professors and embrace your strengths.

Survival tools for a neurodivergent brain in academia

Working in academia is hard, and being neurodivergent makes it harder. Here are a few tools that may help, from a Ph.D. student with ADHD.

Quieting the static: Building inclusive STEM classrooms

Christin Monroe, an assistant professor of chemistry at Landmark College, offers practical tips to help educators make their classrooms more accessible to neurodivergent scientists.

Hidden strengths of an autistic scientist

Navigating the world of scientific research as an autistic scientist comes with unique challenges —microaggressions, communication hurdles and the constant pressure to conform to social norms, postbaccalaureate student Taylor Stolberg writes.

Richard Silverman to speak at ASBMB 2025

Richard Silverman and Melissa Moore are the featured speakers at the ASBMB annual meeting to be held April 12-15 in Chicago.

Women’s History Month: Educating and inspiring generations

Through early classroom experiences, undergraduate education and advanced research training, women leaders are shaping a more inclusive and supportive scientific community.