Battling imposter syndrome

and anxiety in the quest

for an academic science career

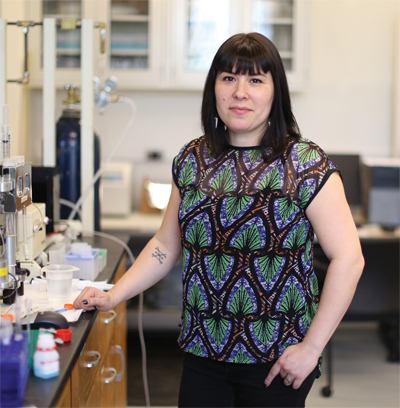

Kelly Chacón is a third-year assistant professor in the chemistry department at Reed College in Portland, Oregon. She talks about her nontraditional career path, confronts the stigma surrounding mental health in academia and shares the experiences that fuel her scientific pursuits.

Kelly Chacón didn’t think of herself as a science-minded child and earned her GED at the age of 22, but she is now a third-year assistant professor in the chemistry department at Reed College in Portland, Oregon.Courtesy of Thomas Humphrey

Kelly Chacón didn’t think of herself as a science-minded child and earned her GED at the age of 22, but she is now a third-year assistant professor in the chemistry department at Reed College in Portland, Oregon.Courtesy of Thomas Humphrey

How did reach your current position?

I had a nontraditional path to science and academia. I dropped out of high school at 15 and went into food service. I did not obtain my general equivalency diploma until I was 22.

Once I caught the learning bug, a key decision was not to allow any “what-ifs” or naysayers to deter me from continuing to learn and progress. I had to begin my journey with prerequisite community college courses in math, writing and science. I decided to make a simple but firm commitment to do my best, to, above all, treasure the privilege of education, and, honestly, to see just how far I could go before it got too hard. As it turned out, it took a fair bit of time, but the sky was the limit. This is true for many of us if we stay positive, ask for help from allies and work really hard.

From a young age, I did not identify as science-minded. However, now looking back to childhood, I should have known that my love of inventing household shortcuts, identifying and foraging for edible local plants, and cooking were indicators of a scientific mind. But, as a society, we may overlook these types of traits in children (especially those from underrepresented groups and/or of low socioeconomic status) and neglect to cultivate those interests into a future science, technology, engineering or math career. So I first learned about biochemistry as a field when I was 24, in a prerequisite community college biology course, during a discussion of the Miller–Urey spark chamber experiment. I was fascinated by the idea that life could have arisen from just a pool of chemicals and wanted to learn more.

Were there times when you failed at something you felt was critical to your path? If so, how did you regroup and get back on track?

Sigh. Yes, there have been some tough spots. I very nearly failed one portion of my qualifying exam as a third-year graduate student and was very harshly criticized for it. The professor who administered that portion said a score so low was an indicator that I should not be in science. This came on the heels of trying to write my first scientific manuscript for publication, which also wasn’t going so well and also had received some harsh criticism. Although many know about imposter syndrome, few realize how particularly intense and devastating it can be for those from underrepresented groups. I immediately went into a tailspin because I had worked incredibly hard on both tasks and it hadn’t been enough. The most important thing that I did at that point was to seek out my university’s mental health resources and find a qualified therapist to talk to. I was scared to seek help, and, in my family, mental health was not something people talked about. But getting help changed my outlook, and I still see a therapist from time to time, specifically to deal with imposter syndrome and anxiety as it affects me as a minority in academia. I speak out about this now to reduce the stigma.

The Research Spotlight

The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology’s Research Spotlight highlights distinguished biomolecular and biomedical scientists from diverse backgrounds as a way to inspire up-and-coming scientists to pursue careers in the molecular life sciences. Eligible candidates include Ph.D. students, postdoctoral fellows, and new or established faculty and researchers. To nominate a colleague for this feature, contact our education department.

What advice would you give to young persons from underrepresented backgrounds who want to pursue a career in science similar to yours?

A) Start doing manageable, small things that matter to you in your community, even though you think you have no time. Make the time. It will pay off in feeling good in the moment and in opportunities down the road.

B) Practice presenting your science in every venue that will have you. High schools, local meetings, national meetings, departmental seminars, courses and lab group meetings are all fair game. Ask for honest feedback and incorporate that feedback into your presenting skills.

C) Practice applying for small research grants, scholarships, travel grants and self-nominating awards. It feels difficult for those of us in underrepresented groups to toot our own horn, but those from privilege do these things without a second thought. Start getting comfortable with honestly and positively assessing your own strengths as a scientist and a person.

D) If you really, deep down, with all of your heart, wish to be in academia but are feeling insecure based on what other people have told you about the job market, stop waffling and make a firm decision to pursue your dream. Make it real by sharpening your focus: What schools/areas would you like to work in? What kind of research would you like to pursue? Then, look at those schools and what they value and represent. Start doing things early on that will contribute to your CV toward the goal of appealing to those schools. And then, when a job comes up, apply for it. Don’t overthink, just try. And don’t be afraid to ask for help from those who supported you along the way.

What are your hobbies?

Sewing and altering clothing (I am short), cooking exotic meals, playing steel-tip darts, drawing and painting, and playing video games like the Final Fantasy series and Fallout.

What was the last book you read?

“Wizard and Glass” by Stephen King. The Dark Tower series by King is some entertaining fiction.

How have heroes, heroines, mentors or role models influenced you?

My mentors and role models are the strong women in science who gave me blunt advice when I needed it. My heroine is mi abuela, Mama Cande. My grandmother was married at 14, could not read, and gave her life to her eight sons and her pueblo. She was so full of love, curiosity and acceptance, and I am driven to make her proud of me even though she is no longer with us.

What keeps you working hard every day?

Real talk: An app called Self Control that keeps me from playing on the internet while I work. But, intrinsically, what keeps me going is that I still, even now, want to see how far I can go before it gets too hard. And I want to contribute something small, before I leave this Earth, toward understanding how our amazing universe and life works.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

The timekeepers of proteostasis

Learn about the cover of the winter 2026 ASBMB Today issue, illustrated by ASBMB member Megan Mitchem.

Defining JNKs: Targets for drug discovery

Roger Davis will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award in Biomedical Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Building better tools to decipher the lipidome

Chemical engineer–turned–biophysicist Matthew Mitsche uses curiosity, coding and creativity to tackle lipid biology, uncovering PNPLA3’s role in fatty liver disease and advancing mass spectrometry tools for studying complex lipid systems.

Summer research spotlight

The 2025 Undergraduate Research Award recipients share results and insights from their lab experiences.

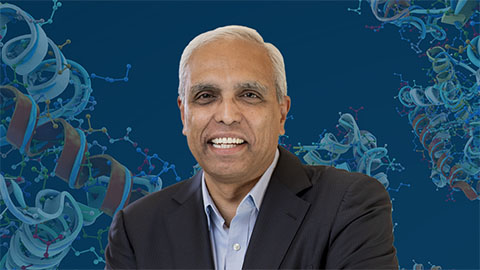

Pappu wins Provost Research Excellence Award

He was recognized by Washington University for his exemplary research on intrinsically disordered proteins.

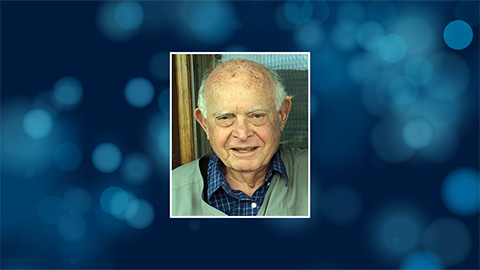

In memoriam: Rodney E. Harrington

He helped clarify how chromatin’s physical properties and DNA structure shift during interactions with proteins that control gene expression and was an ASBMB member for 43 years.