Seeking refuge in science

My parents and my father’s sister left Vietnam in late 1981, while my mother was in her second trimester carrying me. The U.S. war in Vietnam ended with the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975. Over the next two decades, more than 1.2 million Vietnamese people fled the country. Of those, 700,000 left in fishing boats to escape the tumultuous political climate.

To escape Vietnam on a fishing boat meant risking one’s life for an unforgiving journey — three to five days in the open ocean with only the food you could carry, and the fear of being attacked by pirates or caught and imprisoned by the Viet Cong.

The open water journey took my parents to an Indonesian refugee camp. The fishing boats had to maneuver around Singapore’s waters, where a military blockade was formed to prevent refugees from entering its borders. They landed on one of two remote Indonesian islands (each housing about 15,000 refugees), one dedicated to resettling Cambodians fleeing the Khmer Rouge and the second for the Vietnamese. After I was born, we lived in the refugee camp for a year. My father describes the camp as a place no one wanted to live, filthy and chaotic. My mother does not speak of it.

Because of an agreement between the U.S. and the Vietnamese men who fought alongside Americans against the Viet Cong, my father, mother and I were selected to immigrate to the U.S., while my aunt went to Australia. We resettled just north of Washington, D.C. in the Maryland suburbs. For the first few years, we relied on the kindness of relatives who immigrated before us and assistance from our church. My mother had a middle school education and my father had attended high school. Throughout my childhood, they incessantly emphasized the importance of education for my sister and me.

My upbringing instilled in me a strong will. My parents each worked two to four jobs, 12 to 16 hours a day, for most of my childhood. When my friends’ parents were making dinner and helping them with their homework, I was making dinner and helping my sister with her homework. Failure wasn’t an option.

After completing high school in 1999, I received a full academic scholarship to Montgomery College, a local community college, and a scholarship to attend a summer semester at Cambridge University, all through the Montgomery Scholars program.. That same year, I began my internship training at a local proteomics biotech company.

I transferred to the University of Maryland, College Park, and completed my bachelor’s degree in 2003, continuing my scientific training under the supervision of Marco Colombini and Leah Siskind in membrane biophysics. In 2005, I rotated to Zhongchi Liu’s lab where I trained in plant genetics and graduated with my Ph.D. in 2009.

In 2017, I had the rare opportunity to go back to the refugee camp where I was born. It is now a museum and memorial honoring the lives of those who did not complete that three to five-day ocean journey. I saw the 1,500-square-foot hospital where I was born, the replica models of the shacks that temporarily housed the families, and images of children and grandparents being lowered into the ocean because they did not survive the journey. No one had ever told me the story of what the Vietnamese boat people endured, and seeing it in documented detail was humbling and emotional. I felt fortunate and grateful that I was too young to remember.

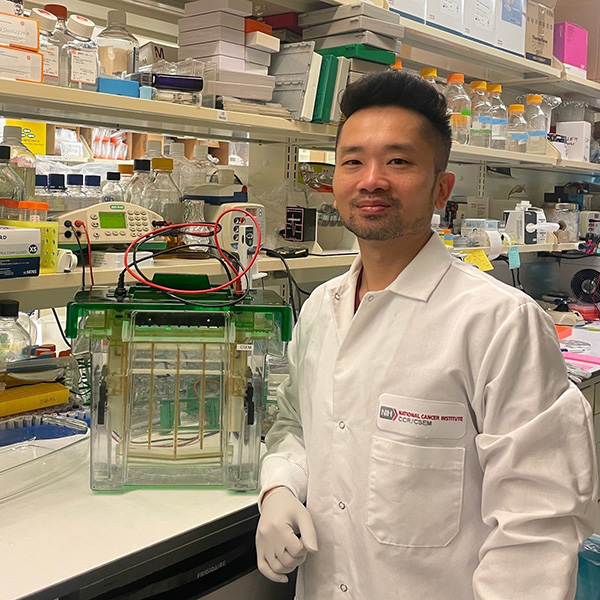

Refugee children often feel a need to make our parents proud after they risked everything to give us the opportunities their country of origin could not afford them. In 2009, I was the first, and am still the only, member in my immediate and extended family to earn a doctoral degree. That same year, I was recruited to the National Institutes of Health under the direction of Yamini Dalal, where I now conduct research in centromere biology using genetic, biochemical, biophysical and cell biology approaches.

Throughout my years as a researcher, I’ve seen a great diversity of people in labs — diversity in skills, expertise and way of thinking. Sometimes a trained geneticist encounters a problem, but it takes a biochemist to find a solution. Be it our racial background, upbringing or gender, diversity helps advance science by filling in gaps; each person alone is not equipped to address every question. Immigrants make up 25% of the STEM workforce in the U.S., adding our unique approach to questions from angles others may not have thought of.

After 15 years at NIH and 25 years as an experimentalist, I can confidently say that, as a refugee-born immigrant, my scientific education and training have been rigorous, my underrepresented views and strong-willed approaches are valuable, and my passion and love for science remain persistent.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

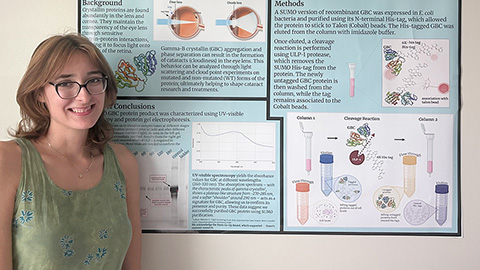

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.