What I wish people understood about science at a small college

Sometimes people ask me why I chose to attend a small liberal arts college to pursue a basic science degree. I won’t tell you that attending a small school is the best choice for everyone, but it was the right decision for me.

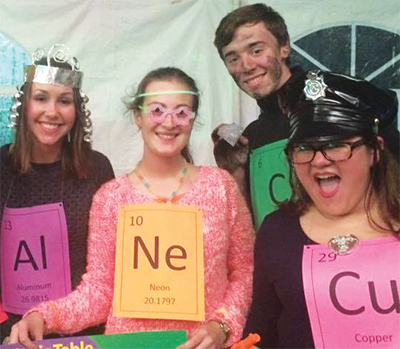

Kerri Beth Slaughter, left, and fellow science club members dressed up as elements from the periodic table to hand out candy at Milligan College’s Trunk or Treat.Courtesy of Kerri Beth Slaughter

Kerri Beth Slaughter, left, and fellow science club members dressed up as elements from the periodic table to hand out candy at Milligan College’s Trunk or Treat.Courtesy of Kerri Beth Slaughter

As a kid in public school, I always made good grades, but my teachers thought I was shy. I rarely spoke up to answer questions. I preferred to listen and observe instead of jumping into the discussion. When I began looking at colleges, I was daunted by the idea of attending a large university with freshman classes of 100-plus students.

I eventually interviewed for scholarships at Milligan College, a small Christian school nestled in the Appalachian Mountains of East Tennessee. The campus had fewer students than my high school. During my interview, I met with three professors and the college president. Although I was a little nervous at first, I started to feel at ease as I talked with them about my goals and interests in science. They helped me feel comfortable in my own skin, and I was impressed by how much they enjoyed engaging with students.

A few months later, I sat down at a desk for my first class in the Milligan science building, built in 1972; the funky architecture and funky smells were the first things I noticed. I didn’t realize how much I would learn and grow there during my four years in college, not because of the building itself but because of the professors who invested in me.

Richard Lura taught organic chemistry and biochemistry, two classes that often inspire a love–hate relationship for science students. He never used PowerPoint slides or tried to integrate technology in the classroom. Rather, he transformed a basic science class into an interactive discussion and learning experience.

For the first lecture of each new unit in organic chemistry, instead of plowing through the details of the next chapter, Dr. Lura gave a broad overview of the material. He engaged the class in discussion about where we might find organic compounds in our daily lives or in industry. After studying for the previous unit’s exam, this discussion helped me remember the big picture of what I was learning.

Dr. Lura sometimes asked students to act out chemical reactions so we could visualize what happens at the molecular level. These comical demonstrations, such as modeling nucleophilic substitution reactions, helped me develop a deeper understanding of chemistry instead of simply memorizing the material. The class interactions also encouraged camaraderie among the students, and we spent many hours helping each other solve problems to prepare for exams.

My biology professor was Michael Whitney. In one of our cell biology classes, he handed each student a container of Play-Doh, and we spent part of the period molding actin monomers and tubulin dimers to learn about assembly of the cytoskeleton. Beyond being a fun activity for the students, Dr. Whitney’s effort to help us become visual learners sparked my fascination with the cytoskeleton, a topic that will be a significant focus of my dissertation research.

At Milligan College, I grew close to the community of science professors and students as we learned together in the lab and classroom. My professors changed science from words in a textbook to something that I could see, touch and imagine. They helped me learn how to ask thoughtful questions about science instead of accepting what I was told as fact.

My professors also taught me how studying science could strengthen my Christian faith, and they provided a safe space to discuss controversial topics. Over time, I found myself speaking up in class more often to answer questions and build on class discussions. I was no longer the shy kid sitting quietly in the corner of the classroom.

By senior year, I had decided to pursue a Ph.D. in biomedical science so that I could become a science professor like the ones who influenced me at Milligan College. I am now a doctoral candidate in the biochemistry department at the University of Kentucky, and my small-school background has contributed greatly to my success as a graduate student, scientist and communicator.

I’ve never been fond of the phrase “coming out of your shell,” perhaps because I heard it too often as a kid. However, I wholeheartedly believe that my professors at Milligan College helped draw me out so that I could reach my full potential as a scientist.

Scientists can be born in the absence of state-of-the art research facilities and millions of dollars in funding. Sometimes all you need is a creative professor, an eager student and a bit of Play-Doh.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

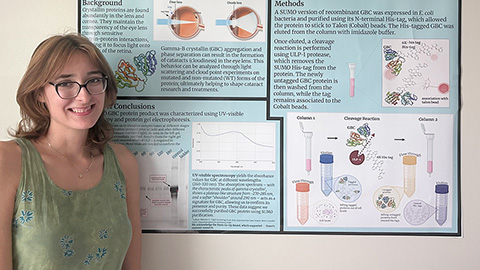

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.