The measure of success

I was sitting in my office one day when a student poked his head around the door and asked, “Andrew, do you have a minute? I’d like to talk to you about something.”

Even though I was behind on deadlines (nothing new in my world), I said, “Of course!”

He started talking about what he wanted to do once he defended his thesis. With hesitation (and with what he later told me was concern about disappointing me), he mentioned that he wasn’t sure he wanted to go into academic science, to which I responded without hesitation (and with what I must admit was a little relief), “Well, what do you want to do when you grow up?”

It’s important that our students be made aware that academic science is not the only career path available to them.

I always say that it takes a special kind of crazy to go into academic science. I have that special kind of crazy. However, I realize that not all of my students have it, will have it or even want to have it.

I do my best to be transparent – to let my students see what I deal with as an academic research scientist. Granted, I don’t let them see all of the warts (no need to scare them unnecessarily); however, I make sure that they see the reality of being a faculty member in the academic world, and I let them decide if that is what they want to be too.

I also let them know about career paths that are available to them. I’ve been in the academic world for nearly 25 years. Along the way, I have made many friends who have followed many different paths. They have become faculty members at teaching colleges, high-school science teachers, administrators in curriculum development, researchers in industry, entrepreneurs for startups, program officers at federal agencies, scientific writers and editors, lawyers specializing in intellectual property, activists in scientific policy, sales representatives for scientific companies, and — yes — even faculty members at research universities.

All the people on this diverse list identified career paths for which they are passionate, developed the skills they needed, took advantage of opportunities (both planned and serendipitous) and, most importantly, applied the critical-thinking skills they developed in graduate school and their postdoctoral positions to bring a new depth and vitality to their chosen careers.

A big part of being a mentor, for me, is getting to know my students and figuring out exactly what it is that they want to do once they earn their Ph.D.s. I tell them, “This is your degree. You do with it exactly what you want. Ultimately, it’s your life, you’re the one that has to go to work every day, and you have to be happy!”

I also make a point of telling them what I see as their strengths and weaknesses and of telling them what I hear them saying over a beer at the local bar on our regular lab outing. My students have gone on to become, among other things, a translational research physician, a technology transfer and intellectual property specialist, a burgeoning scientific writer and editor, a future director of a molecular genetics diagnostics lab, and even an assistant professor.

To the members of a Ruth L. Kirschstein training grant study section, I would not necessarily be considered a successful sponsor, because only one of my five students stayed in academic science. (Trust me, I know. I’ve heard it said many, many times while sitting on these study sections myself.)

However, to me, I am successful beyond measure, because I have molded minds that can think critically about science and about their lives. I have tried, as a mentor, to give them the confidence, freedom, support and opportunity to follow whatever paths make them happy. I’m extremely proud of every single one of my students – or, as I call them, my kids – and rejoice whenever they excel in their careers and in their lives. This, to me, is success. And this is what we, as mentors, need to do for our students.

Students, you also must realize that once you have your degree, the sky’s the limit. It’s up to you to figure out what makes you passionate, follow that passion, never give up fighting until you achieve your goal and, most importantly, understand that you can achieve whatever you put your mind to.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

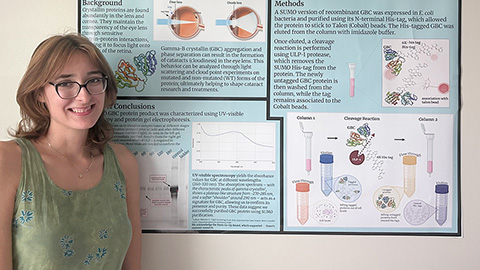

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.