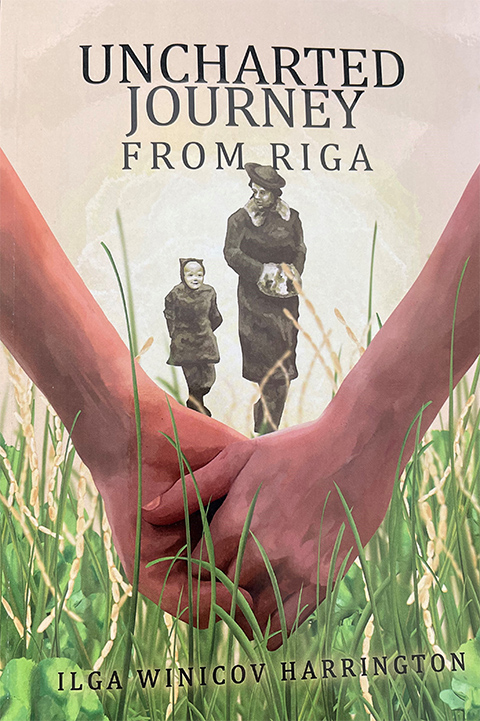

An uncharted journey

The author was born in Riga, Latvia, in 1935 and spent her childhood under Soviet and German occupation. During and after World War II, her family lived in a German labor camp and a displaced persons camp. In 1950, they sailed to the United States and settled in Pennsylvania. She earned a Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania in 1971.

These edited excerpts are from her memoir, “Uncharted Journey From Riga,” published in 2022.

Close look at the food chain

Although we lived in the capital city of Riga, I spent two summers on farms, the second during my last year in Latvia.

One morning, the men had gone out to the fields, and so had most of the women. I was home with the cook and the timid house servant, Liene. The cook was planning to have chicken for dinner and asked Liene to go and kill the chicken so that she could get it ready for later in the day.

Liene started to cry. “No, no, I can’t do it! Kill a chicken, never!”

The cook was beginning to get agitated, but she apparently considered the job beneath her station and was not about to do it herself.

Without thinking, I said, “Never mind, I can do it.” After all, I had seen John, the hired man, do it a couple of times. All you had to do was catch the right chicken, take it to the tree stump behind the hen house, hold its head to the block, and take the axe and chop off its head with your other hand.

The cook looked a bit dubious. “All right, I guess.”

Liene started to cheer up. “When you are done, I’ll pluck it,” she offered. So the three of us went out to the henhouse. The cook gave me the axe, which I leaned against the dark stump. She then picked out the unsuspecting chicken and handed it to me. Liene had disappeared.

At that point, the chicken must have become suspicious, and I had a bit of trouble holding it under my arm. Not surprisingly, it did not want to lay its head on the block like a compliant victim. Finally, I managed to wedge it with my knee, and, anxious not to let it loose, I raised the axe, and with one blow the chicken’s head rolled on the ground. What happened next both shocked and scared me. Besides the amount of blood, the now headless chicken did not fall to the ground but staggered around the small clearing, finally falling with its feet still twitching in the air. The cook calmly picked it up and went to the house.

I stood frozen. Without any forethought, I had killed an animal. The chicken must have been in such agony as it staggered around there. The eye in the severed head stared at me from the trampled grass on the ground.

I could not eat chicken that night. The adults were understanding.

This scene came to haunt me many years later. I was a research assistant in a laboratory at Temple University School of Medicine in Philadelphia. We studied liver biochemistry in rats and measured liver enzyme activity after various treatments. The rats had to be sacrificed with a guillotine before excising the liver and subjecting it to various biochemical analyses. After barely managing to dismember one rat the first day, I acknowledged that I simply could not do this task. Fortunately, the lab director was sympathetic and found one of the other technicians for that part of my job.

Welcome to the labor camp

One midwinter morning at the labor camp school in Leipzig, the authorities decided to check on our progress to see if we had learned sufficient German to salute the Fuhrer in the proper manner on state occasions. The assistant commandant arrived in his brown uniform with the SS insignia on the collar, black belt with the revolver at the side, high black boots spit shined, carrying his hat under his arm, and a small truncheon in his hand.

He made rounds of the classroom, checking our notebooks. So far, so good! But then he wanted some of us to demonstrate our pronunciation and answer simple questions in German. The teacher called on some of the better students, and again, everything went well. Until … the assistant commandant picked out the tallest boy in the class and asked why he was not working in the factory. He certainly looked old enough. The boy, not one of the brightest students, stood up and just stared; the question was too complicated for him to understand.

While the irritated man turned to the teacher, one of the other boys made a rude noise behind everyone’s back. The man jerked back in fury, and, swearing in words none of us understood except for the inevitable “verfluchte Auslander” (cursed foreigner), started to hit the standing boy on his head with the truncheon he carried. The teacher stood stony-faced while the boy crumpled over his desk, shielding his head with his arms, but the man did not stop.

Without thinking, I jumped up and shouted, “Nein, nein, er hat es nicht getahn!” (No, no, he did not do that!)

Suddenly, it was deathly quiet in the class. The man turned to me with the raised truncheon, said something very quickly to the teacher, spun toward the door, and left. We rose quickly, but the door was already closing behind him.

That evening, a guard came in the dining hall and asked that mother and I accompany him to the administrative building. After some wait in the hallway, we were shown into the commandant’s office.

It was a warm, well-lit room with colorful rugs on the floor and a large desk, behind which sat the man who had come out on the steps and addressed us on the day of our arrival. His pale eyes speared me across the room, and in an angry voice, he asked if I had shouted at the assistant that day in school. I managed to answer, “Ja.”

I felt he needed an explanation. My German was not good, so I told him in Latvian that an innocent child was beaten. Mother took a deep breath and translated my words. There was a long silence, then the commandant got up and came around the desk.

“Komm her,” he said in a firm voice.

I slowly walked toward him and focused on the toes of those polished boots glinting ominously in front of me. I was afraid to look any higher and hoped he did not have a truncheon in his hand.

If he had one, I did not want to see it coming down on my head.

We stood like that for what seemed a long time, and, suddenly, he put his finger under my chin and made me look up at him. His voice was firm but not angry as he berated me, though I only partially understood him. The essence of his words was that if I wanted to avoid serious punishment, I was never to shout and challenge my superiors again. I can still hear his emphatic voice: “Niemals, niemals!” (Never, never!) After that, he dismissed us.

Mother and I were badly shaken.

“We were lucky,” was all mother could say.

The joys of being a grad student

As I settled into the fall routine in the University of Wisconsin bacteriology department, I found my days full of classes that I needed to take as a first-year graduate student. These included Soils and Food Bacteriology. The Wisconsin bacteriology department was focused on bacterial physiology and the practical applications of knowledge of the microbial world. We learned the sequence of organisms that were required to make sauerkraut and even made mead from yeast and honey.

My rounds of faculty offices to find an advisor for a project that I might undertake for my master’s thesis were somewhat disappointing. Most of the faculty preferred to take on Ph.D. students in their laboratories, since it meant a longer commitment. So I was pleased to find that Dr. Elizabeth McCoy would take me on for a project looking for bacterial viruses that might be causing toxin production by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum, a lethal food pathogen. A couple of other laboratories recently had shown that this was the cause of toxicity in a different disease organism. Since botulism was the cause of death from food poisoning, it was worth investigating whether a similar latent bacterial virus was the reason for toxin production in C. botulinum.

This meant spending the next year and a half growing these toxic organisms anaerobically with fermenting oats, which used up most of the oxygen in the sealed jar. We needed to duplicate the natural growth conditions in sealed cans of food with little or no acidity, where these bacteria produced their most lethal toxin. In the days before mechanical laboratory pipettors, this meant transferring the toxic liquid by mouth pipetting.

This process, using a pipette as a long glass measuring straw, required me to suck up the liquid with my mouth to the desired level, quickly put my finger on the top of pipette to stop the liquid, and then transfer the contents of the pipette to another container by lifting my finger to release the liquid. It was very important to stop the sucking process well before the liquid got to my mouth, since a small amount of the stuff would readily kill mice. Mouth pipetting makes an excellent lesson in concentration on your work. Needless to say, I have never been tempted to get Botox treatments.

Adult education

There were still very few women graduate students in biological sciences and even fewer at the postdoctoral or faculty level. However, Lewis Pizer’s lab at the University of Pennsylvania probably had more than the usual number of female members.

Helene Smith, who would make significant contributions in cancer research, just had graduated. By the time I arrived, Margaret Miovic was about to graduate. Margaret eventually became a pediatrician, but at the time, she was the only other person I knew who was in graduate school, was married and had small children. Roz Eisenberg came to the lab as a postdoc a year later. She showed that it was possible to progress even further in academia and juggle the responsibilities at home with those in the lab.

At the time, Helen Davies was the only woman faculty member of the microbiology department. For years afterward, I would recall her advice whenever, due to my back problems, I was teased by my male colleagues about women being “too weak to do any necessary heavy lifting in the lab.” I would smile sweetly and quote Helen. “Please lift this for me. I will be happy to do some thinking for you in return.”

New moves in academia

As summer wound down, I needed to finish a couple more experiments, and then I would write my thesis and go on to Bob Perry’s lab at the Fox Chase Cancer Center with my postdoctoral fellowship in hand.

Unfortunately, the last experiments required a very pure enzyme preparation, and Murphy’s law struck. My phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase died on the third and last crystallization step. This meant that I had to go back, grow large amounts of the bacteria and start from scratch. Lew would not let me go with a partially negative thesis.

“If you are going to do something like this, it is worth doing it well,” he said as I told him about my uncooperative enzyme.

Of course, he was right. I went back to the lab. The next purification succeeded, and I was able to finish the experiments and the draft of the thesis.

My thesis committee was kind, but Mildred Cohn went through my writing in her best Journal of Biological Chemistry editorial style. Those pages had a lot of red ink on them, and it portended much of my future interactions with journal editors.

And then it was over. I was awarded my doctorate, and I remember thinking, “This was such a lot of work, but I don’t feel any different.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Sketching, scribbling and scicomm

Graduate student Ari Paiz describes how her love of science and art blend to make her an effective science communicator.

Embrace your neurodivergence and flourish in college

This guide offers practical advice on setting yourself up for success — learn how to leverage campus resources, work with professors and embrace your strengths.

Survival tools for a neurodivergent brain in academia

Working in academia is hard, and being neurodivergent makes it harder. Here are a few tools that may help, from a Ph.D. student with ADHD.

Hidden strengths of an autistic scientist

Navigating the world of scientific research as an autistic scientist comes with unique challenges —microaggressions, communication hurdles and the constant pressure to conform to social norms, postbaccalaureate student Taylor Stolberg writes.

Black excellence in biotech: Shaping the future of an industry

This Black History Month, we highlight the impact of DEI initiatives, trailblazing scientists and industry leaders working to create a more inclusive and scientific community. Discover how you can be part of the movement.

Attend ASBMB’s career and education fair

Attending the ASBMB career and education fair is a great way to explore new opportunities, make valuable connections and gain insights into potential career paths.