Regeneration of a transgenic mouse model

Nicole Ward came upon her psoriasis mouse serendipitously. Ward, an associate professor in the department of dermatology at Case Western Reserve University, was working in the department of anatomy there when she discovered the mouse. A neuroscientist by training, she was studying how nerves and blood vessels influence each other’s development. Ward was using a transgenic mouse line, the keratinocyte-Tie2 or KC-Tie2 mouse, to manipulate cells in the skin and study how they changed the surrounding blood vessels and nerves. She noticed that the skin of these mice was patchy red and scaly like that of her father, who suffers from psoriasis.

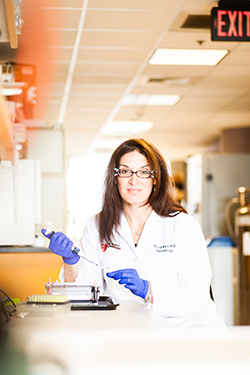

Nicole Ward

Nicole WardWard’s office happened to be across the hall from faculty members in the dermatology department, and she interacted with them every day. After two years with the anatomy department, she joined the dermatology department, moved across the hall and started characterizing the mouse she was using to study nerve development as a model of psoriasis.

The KC-Tie2 mouse is a remarkably accurate model of psoriasis. Ward and her research team showed that the skin disease developed by the mouse is very similar to human psoriasis physically and biochemically. The mouse also responds to drugs that work in patients and, more impressively, does not respond to drugs that do not work in patients.

“Most of the time when people are testing their models against human disease, they just make sure that the drugs that work in patients work in their mouse model. We’re really aware that it’s equally important to demonstrate that drugs that have failed in clinical trials, that don’t improve

the patient’s disease, also fail in the mouse model,” Ward says. “So this mouse has been able to do that.”

Results from the KC-Tie2 mouse have been translatable to psoriasis patients. Ward’s latest findings were recently published in the journal Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. See a related story in the Journal News section of this issue.

Because the KC-Tie2 mouse was developed originally to study nerve development, the fact that it developed psoriasis suggested a connection between the two. This link has been observed anecdotally in psoriasis patients who have undergone knee surgery. After the procedure, “the (psoriasis) plaque on the knee that was operated on goes away so there was speculation among the clinical dermatologists that perhaps the nervous system was contributing to the disease,” explains Ward. “There are other similar reports of injury to the nervous system and then remission of the psoriasis in the areas where the nerves had been damaged.”

To elucidate the basis for these observations, Ward and her team surgically removed the nerves from the skin of the KC-Tie2 mouse, and the psoriasis improved. After figuring out that certain neural peptides were elevated in the psoriatic skin, they removed the nerves in the skin and put back only the peptides. The psoriasis returned. To verify the causal role of the peptides, they kept the nerves in the skin but blocked the release of the peptides, and again the disease went away.

Since Ward moved across the hall in 2005, she has been investigating psoriasis and skin inflammation full-time. Ward has not left behind her neuroscience roots, though.

“I’m lucky I get to play a little bit in the neuroscience sandbox because psoriasis is a very cool disease if you’re studying disease pathogenesis. You have so many cell types that are contributing to the inflammation. You have the keratinocytes, the nerves, the blood vessels and all those immune cells,” she says. “I always tell patients when I’m talking to them, ‘You know, the disease is absolutely fascinating at the scientific level.’ It’s like a big, ginormous nerd alert, right? But it’s like so, so cool.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

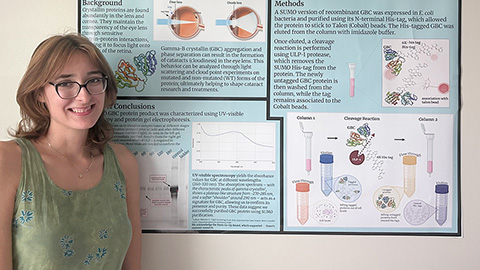

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.