Permission to break down

The effects of fasts on cells are a good analogy for what happens when we step away from work. Let’s make intermittent resting a thing.

You’re looking at those unpacked boxes cemented as housing blocks on the skyline, determined to be permanent. Clothes lounge like teenagers, and the gray layer of dust is a stratus cloud.

Or maybe your data is half gathered or part processed. Your code is not quite there. Your figures are relatives who have overstayed, and you retreat to the kitchen to escape their gaze: awkward and expectant.

You’re tired, and some things have accumulated.

Your cells likewise face that famous economics principle — scarcity — and in these moments they deliver doses of both realism and aspiration. Your body, with all its biochemistry, is still human. Well-oiled machines that they are, even cells conserve energy sometimes by not immediately sorting through proteins that loiter after a job is complete. Not everything is in its place. While it’s accurate to picture cells as teeming with organized life, there is actually a degree of clutter. Take comfort.

The memory

I realized the importance of intermittent rest in my first year of graduate school. After working in the lab for a year on my undergraduate thesis, I was teaching secondary school and wanted to talk about science all the time, no longer bookending those conversations into seminars.

Around 1:50 a.m., my housemates would tell me I needed to sleep. I’d finish the lesson on atomic theory for Year 11 Chemistry and close the laptop. Taking a shower became a window in which I could not work.

Late in the year, I went out for dinner for a friend’s birthday on a school night. That this was noteworthy is a telling landmark of that time.

The aspiration

The aspiration our cells offer is a paradox. Experts in signaling and production, enjoying a go-go-go lifestyle with side hustle aplenty, even cells benefit from taking a break. In stepping away during a fast from the typical pace of building — of anabolism in its varied forms — our cells may see a host of benefits.

Our cells’ response to fasting, laid out clearly in a couple of reviews in the New England Journal of Medicine and the journal Nature, provides a useful analogy: We, too, may take breaks from production. We’re not talking months off; I suggest regular, sustainable rest. Consider the Sabbath or a daily practice, a sun salutation or a scheduled walk, after which you can resume with some helpful rewiring.

What might cells’ responses to calling a timeout teach us?

Switch your fuel

One weekend in that first grad school year, a teacher friend and I wrote a list of the things we wanted to do in our new city. We decided to visit one place each weekend. In hindsight, the lessons I learned then were just the ones I needed years later when I was studying life science. One day each week was not for planning another experiment or entering more data. It was for switching fuel.

A cell that switches from glucose-derived fuel to ketone bodies in fasting is later better able to resist metabolic, oxidative, ischemic and proteotoxic stress. It is less prone to getting worked up: inflammation. It is able to grow.

We aren’t just what we eat; ponder the sources of all you consume and whether that consumption is passive. The benefits our cells realise after fasting can be mirrored in our own lives by refocusing our fuel from what is constantly coming in — the carbohydrates of media, management or misguided advice — to what we’ve stored away earlier or never noticed.

In the time stolen from consumption, we can remember what fuels us and ask what gives us energy even as we give. Step away from the things you usually read or hear. Listen to your breath. Consider the lilies. Be beautifully, refreshingly bored. Or put down your book and surrender to the chaos of nieces and nephews. Church pews themselves don’t promise renewal, but you can stretch out, with silence, together, and watch the light filtering through stained glass.

Stop accumulating

Another evening, a friend invited a guest speaker to his home. We crammed onto couches in the loft with soft orange light on wooden walls. I listened to her epiphany on rest. She had been completing her Ph.D. in English literature at Cambridge. What she could read was endless; there was no end to further thoughts. Yet by her third year, she chose to rest — read only for pleasure — one day a week. I thought, “If she can choose this, I can too.”

When our cells fast, protein production slows. Our cells need not constantly make to stay alive. If we can realize a healthy, evolutionarily conserved equilibrium in our cells, can we realize it for our very selves?

In the frizzled factory of a fasted state, your cells take stock. They throw together a meal from loose ends, clearing clutter. Old proteins forming part of the furniture? Marie Kondo that shit. To one protein, “Thank you for your service.” Recycle. To another, “You know what? You still spark joy.” Reuse.

I don’t think we appreciate the effect this has on the state of our cells. It’s not a sentimental second wind for proteins forgotten; the science in the reviews mentioned above suggests it’s more like a lifeline, extending quality of life if not lifetimes, through the life-changing magic of lysosomes.

Let’s thank the parts of cells that help us do this. Autophagosomes, thank you for gathering with gentleness the old things for sorting. Lysosomes, thank you for having the courage to release aged materials from their former form for reuse. Lipid droplets, thank you for shrinking and expanding in time with our rhythms; you separate and collate lipids that, otherwise accumulating, can be toxic, and in doing so, you relieve us.

Repair and reenter

This time, a drop of memory from when I was in school. My art homework was due the next day, and I was nowhere near done. Dad, relaxed and gentle, suggested I just go to bed. I thought there was no way I could possibly do so, but I did, and I woke up in the morning and finished my homework. My parents knew the power of rest. Mum used to say when I was stressed, “You’ll just have to do the best that you can in the time that you have.” This is realism with aspiration. Rest, and give your best.

What happens when a cell returns from rest?

A fasting cell repairs DNA. When our cells return to their usual comings and goings after a fast, healthy remodeling occurs. Processes are more efficient. What is essential remains. And we feel better than we did before. It’s called refeeding and post-refeeding, and I smile just reading those words.

Disclaimers for days

Let’s clear up some mitochondria. Sorry, misconceptions.

Fasting from work may at first not be pleasant. As with a physical fast, you may feel irritable. You may wonder whether intermittent resting is not for you. Scientists want you to know that fasting improves after you’ve done it a few times. In the case of fasting from work, a shock to your identity may come but not without some productive remodeling. It’s worth it.

Has fasting always been about food? Not exactly. Fasting in terms of resting from one’s usual rhythms is in many ways a return to the focus of traditional fasts. Since long before the popularization of intermittent fasting, people have fasted less for physical reasons and more to make time for reflection; the biochemical effects of fasting are an apt metaphor for the not-just-physical benefits of taking a break. They are ours to reclaim. Fasting is ours to reclaim, to reframe. We can choose a different focus to yield different fruit.

An individual taste

Sometimes, without carving out time, I’ve had fasts of various sorts fall into place, and they paid off.

One time, I bought and consumed a host of delicious Middle Eastern sweets in East London. The next day, drinking tea on the sunny couch in the morning, I realised that I didn’t need to eat until the afternoon; I had preloaded, accidentally. In that time, I read some, studied the tree outside some, journaled some, prayed some, and pondered some. It was toward the end of one job and the start of another, and I am grateful for the unplanned, golden window of time that dawned from those sweets.

Another time, I didn’t drink coffee in the morning, even though I was a teacher, and in the afternoon I played table tennis with some other staff. I never have been known for hand–eye coordination and hated sports for the first half of my childhood, but I won! I felt oddly focused, as though peripheral things were irrelevant and unseeable and sharp-shooter things were streamlined. It’s a memory that’s stuck with me.

These experiences were unexpected, uneventful, solidifying times of rest.

One day, all that is in our cells will break down, resting in the good earth. Until that final catabolism, let us carve out space to consider what a refreshment from old things, in lieu of constant consumption, can bring to not just our bodies but our spirits.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

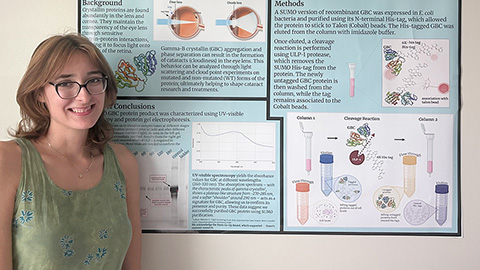

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.