Dancing cancer

Rowland–Goldsmith: Last summer, I received an unexpected request: The chair of my university’s dance program asked me to meet with Jacob Jonas, a visiting choreographer.

In my undergraduate cancer biology course, I teach students how to communicate with nonscientists and, specifically, with cancer survivors, using the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology’s Art of Science Communication course. As a science educator devoted to unraveling the mysteries of cancer biology and a believer in science communication, I’m always open to unexpected collaborations.

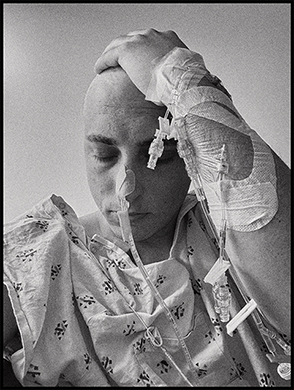

Jonas: When we first spoke, I had been in research for a new work about my experience with cancer — not as an emotional journey, but as a cellular one. I wanted to dig into the science behind it and to understand what was happening inside me on the most fundamental level. I hoped that learning the language of cancer biology could help me translate that chaos into movement.

Rowland–Goldsmith: I was curious, so I agreed to meet with Jacob.

In our first meeting, I introduced Jacob to the fundamental principles of cancer biology — how cells mutate, grow uncontrollably and evade the body’s defenses. But I wasn’t simply explaining cancer biology to a choreographer — I was speaking to someone who had lived on the battlefield, someone who wanted to translate cellular rebellion into a form of beauty.

Jonas: I was most interested in exploring themes of randomness inside the body, metastasis and the mind–body connection – especially how emotional stress can lead to illness.

I was thinking about cells separating from a group and how randomness can lead to growth or disruption, an image that translated easily to a dancer breaking away from the group, disrupting the harmony. I knew that had to be in the choreography. But I wanted Melissa to see the process for herself to understand how the conversation and tools were shaping it, so I invited her to attend a rehearsal. And we began the weaving of two worlds that rarely touch.

Rowland–Goldsmith: At that rehearsal, I saw how Jacob created choreography that reflected the chaotic nature of cells — a dancer moving separately from the rest of the group much as cells break away from the body's rhythm.

I was fascinated when Jacob had the students improvise to ultimately choreograph dance moves showing cells acquiring mutations that led to cancer, and I was so impressed with the physicality of their movements. I saw my research transformed into something visceral, something felt. Science was no longer confined to a laboratory; it was unfolding in the sweat-soaked bodies before me.

At the end of the rehearsal, the dancers gathered around me. I shared some basic elements of cancer biology and drew parallels between what they had just danced and the scientific concepts. I invited them to visit a colleague’s lab to look at cancer cells under a microscope, breaking down the walls that typically separate our disciplines.

Jonas: When Melissa spoke with the dancers, helping them see the biology within their movements, they weren’t just dancing anymore; they were embodying a story about cellular rebellion, about the body’s defenses being tested.

In the following weeks, our collaboration deepened. I visited Melissa’s cancer biology class — on a day she brought in a poet to talk about the intersection of science and art.

That experience impacted me deeply. Not having excelled academically, I valued connecting in an academic environment and feeling so much care and knowledge. That day reminded me how communication across disciplines and fields can bridge gaps. I saw how the students were trained to communicate their research in ways that reached beyond science, to deeply understand humanity and empathy, and that all work needs curiosity and dialogue.

Rowland–Goldsmith: Many of my students told me that the class Jacob attended was — by far — the most impactful and life changing they’d experienced at that point in the semester.

Jacob returned the favor and invited me and my entire class to attend a dance performance. My students watched dance, some for the first time, and saw how movement could transform abstract scientific ideas into something felt and understood on a deeper level.

Jonas: Since then, we’ve been exploring what more we could do together. There’s a sense of possibility in the way we are bridging biology and dance. The power of the arts and sciences working together can shine light on the importance of innovation and expose new ways of thinking, bringing value to different areas of focus. For now, we’re letting it unfold, seeing where it takes us.

Rowland–Goldsmith: Our collaboration shows that when science and dance collide, we can create something new — a dialogue that transcends traditional boundaries, offering deeper insights into our cells, mind and body.

Jonas: That transcendence has been the most powerful part of this process. We are not only communicating knowledge but inviting people to experience it, to feel it in their bodies. That's a different kind of understanding, one that reaches beyond words. And, in the larger sense, something that brings us closer to understanding health in a more holistic way.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Sketching, scribbling and scicomm

Graduate student Ari Paiz describes how her love of science and art blend to make her an effective science communicator.

Embrace your neurodivergence and flourish in college

This guide offers practical advice on setting yourself up for success — learn how to leverage campus resources, work with professors and embrace your strengths.

Survival tools for a neurodivergent brain in academia

Working in academia is hard, and being neurodivergent makes it harder. Here are a few tools that may help, from a Ph.D. student with ADHD.

Hidden strengths of an autistic scientist

Navigating the world of scientific research as an autistic scientist comes with unique challenges —microaggressions, communication hurdles and the constant pressure to conform to social norms, postbaccalaureate student Taylor Stolberg writes.

Black excellence in biotech: Shaping the future of an industry

This Black History Month, we highlight the impact of DEI initiatives, trailblazing scientists and industry leaders working to create a more inclusive and scientific community. Discover how you can be part of the movement.

Attend ASBMB’s career and education fair

Attending the ASBMB career and education fair is a great way to explore new opportunities, make valuable connections and gain insights into potential career paths.