Connecting with Legos

Legos were my favorite toy as a kid. I had a 5-gallon tub of pieces that I slowly accumulated over birthdays and other holidays. When I went to college, I reluctantly had to hand off my tub to my younger cousins. I figured that was the end of Legos for me.

I hit some rough patches in graduate school when I felt burnt out. It seemed like I’d forgotten how to take a break to recharge myself. I would waste time on my computer watching videos, and by end the day, I would feel neither productive nor refreshed.

At those times, when I was looking for a pure distraction, I found myself thinking about Legos repeatedly. So once in 2013 and once last year, I went out to a Lego store and bought two large sets, larger than anything I had as a kid. Each time, I felt like I was living some sort of childhood dream — my mind would have exploded at age 12 if I had sets as large and expensive as these. They were a lot of fun to build, and I realized that Legos were still one thing that I really could enjoy without feeling guilty about work.

Once I finished building the second set, I remembered that my favorite part of playing with Legos was breaking everything apart and creating my own things. I now had more than 5,000 pieces from the two sets, so there was a lot that I could do. The first thing I randomly built was a small bathroom. I draped a small minifigure over the toilet to make it look like the figure was retching into the toilet, just because I thought it made for an amusing image.

I wanted to create more things, but I wasn’t sure what to do next. I looked at my small bathroom creation and thought it might be interesting to come up with a story of why and how this minifigure ended up clinging to a toilet. Perhaps because I was in my own head, I decided I would create a short series of pictures where the figure was a graduate student who had a terrible meeting with his advisor. I worked backward to create the four images that ended up coming before it. Once I looped back to the bathroom scene, I was having too much fun. I realized that graduate school offered a lot of ideas for posts, so I decided to keep going.

When I started making these Lego scenes, I only put them up on my personal Facebook account for friends. After a few were posted, some friends suggested that I also put them up on other social media platforms. I had no idea that they suddenly would take off after a couple months of posting. I truly didn’t expect any large number of people to see these posts, much less react so positively to them. (Editor’s note: Lego Grad Student now has more than 9,000 followers on Twitter.)

I first made these as a dark joke to myself (and I fully admit I have a dark sense of humor), but it was remarkable to hear people say that the posts really resonated with them. That was never my intent, but I am glad that these posts can help people feel like they’re not alone.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

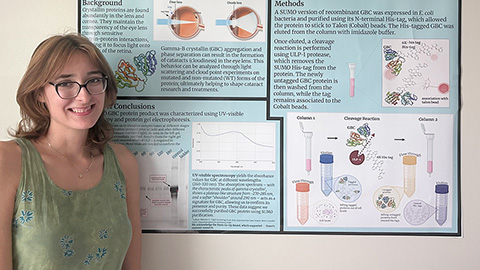

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.