The midcareer move

When Ryan Potts left St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital this summer to become a director at the pharmaceutical company Amgen, he joined the small number of former professors who now hold leadership roles in life science companies.

The Experts

Howard Jacob was a physician–scientist at the Medical College of Wisconsin who rose to prominence after using exome sequencing to diagnose and treat a young patient with a rare genetic anomaly. He left academia in 2015 for a brief stint leading two biotech startups and then joined pharmaceutical company AbbVie in 2018 as its vice president of genomics.

Charlotte Jones–Burton was an assistant professor at the University of Maryland Medical School before accepting a job in clinical research at Merck in 2007. In 2019, after eight years at Bristol-Myers Squibb, Jones–Burton became the vice president of global clinical development in nephrology at Otsuka Pharmaceutical Companies.

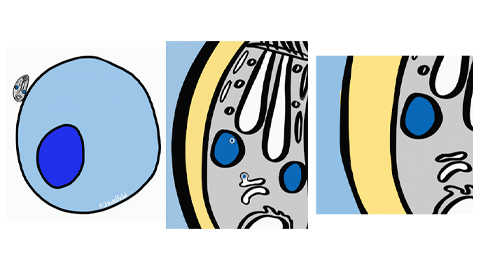

Daniel Ory was a professor at Washington University in St. Louis until 2018, when he moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, as the senior vice president of translational medicine at a young biotechnology company, Casma Therapeutics. As a physician–scientist, Ory focused on autophagy; now he works on regulating the process to treat disease.

Ryan Potts studied the action of ubiquitin ligase-binding proteins called the MAGE family in a lab he started at the University of Texas Southwestern and moved in 2016 to St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital. This year he took a job as the executive director of a new program to manipulate protein binding as a new drug modality at Amgen.

After making it in academia, landing — and holding on to — a job that many people aspire to but never reach, why do Potts and his fellow ex-professors choose to move to a different sector? How do their opportunities arise? And what challenges do they encounter along the way?

ASBMB Today spoke to four former professors to gain some insight into this unusual career path.

Competitive candidates

Carl Cohen, who runs a consultancy teaching leadership skills to scientists, said that career transitions are most common at the junior level, among professors who do not receive tenure or simply decide that academia doesn’t suit them.

This was true for Charlotte Jones–Burton, a physician–scientist who now leads global clinical development as a vice president at Otsuka Pharmaceutical Companies. In 2006, as a junior professor, Jones–Burton said, “I began to say, ‘Where is this going for me?’”

Despite having landed an assistant professorship at the University of Maryland and a transition-to-independence award from the National Institutes of Health, she calculated that to achieve at the level she aspired to, she would need to put in 80 to 100 hours a week at work, splitting time between research and clinical duties. Jones–Burton’s son was very young, and she knew from her years of clinical training how punishing that intense schedule could be.

Still, she said, “I didn’t go looking” for a role in the pharmaceutical sciences. Instead, she got a phone call from a recruiter looking to fill a cardiovascular research position at Merck just as she wrapped up another credential, a master’s degree in epidemiology and preventative medicine focused in clinical research.

After professors receive tenure, according to executive recruiter Dave Jensen, it becomes more difficult to make a transition. “Once you’re pretty far down the (academic) road … employers will look askance and think you’ve made a decision” to work in a culture very different from business, he said. “It is a move that people make, but it’s difficult. And it becomes even more difficult the longer you’re there.”

The years after receiving tenure also can be a time when professors take stock and experience some career dissatisfaction (see “The tenured itch”). Cohen, the leadership trainer, used to be a professor too. His research was going fine, he said. He could have continued to run his lab, bring in grants and pump out papers. But the work “somehow wasn’t lighting my fire any more … and I wasn’t achieving at the level that I really aspire to.”

Cohen had grown more interested in science leadership when he became acting chair of his department and took a leadership role in the American Society for Cell Biology. He found that work more compelling than research. So in 1997, he left his role at Tufts University and St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center to join a company called Creative Biomolecules. He spent about 15 years in various biotech roles before he began to focus full time on his consulting firm.

Jensen, a recruiter who focuses on finding candidates for biotechnology, pharmaceuticals and agricultural sciences, said that a professor who is senior or well recognized in their field has a leg up. “Someone who’s on scientific advisory boards and who becomes known, should they make their desire known to move into a company, they’re always given a high degree of credibility.”

To stand out before that, Jensen said, a would-be ex-professor needs experience in business or a remarkable reputation within their field.

Some academic institutions in biotechnology hotspots give professors opportunities to develop such reputations earlier. For example, two scientists affiliated with Boston’s Broad Institute have transitioned in the last few months to industry leadership: Aviv Regev, who until this summer was a professor at the Broad best known for her work on single-cell sequencing and the ambitious Cell Atlas project, recently moved to Roche’s Genentech research and early development as an executive vice president, while Kevin Eggan, who spent years leading psychiatry research at the Broad and a lab at Harvard, just accepted a position at BioMarin.

Bringing a major project to a successful conclusion helps candidates stand out and also can kindle new career aspirations.

a management training workshop.

That was the case for Daniel Ory, senior vice president of translational medicine at Casma Therapeutics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who left Washington University in St. Louis in 2018. Ory had helped to bring a candidate treatment for Niemann–Pick disease type C to the clinic through an NIH–industry partnership; he was involved in studying cyclodextrin’s effects from preclinical tests in mice a dozen years ago to early-stage clinical tests at the NIH. He also helped recruit a pharmaceutical partner to run final efficacy trials, which recently finished; the Food and Drug Administration is considering the drug.

“I got to help co-lead a team of academic investigators, intramural and extramural NIH investigators, regulatory consultants and also industry,” Ory said. “We worked as a project team, similar to what you do in pharma or biotech.”

The experience, which helped prepare him for his current job, also motivated him to seek it; developing the drug felt like some of the most important work he had done. “I didn’t think it was likely I was going to get another opportunity to do this in my position in academia,” he said. “It seemed to me that this time I needed to go out and seek those opportunities directly.”

Offers and networking

While still a professor, Ory had met the staff at Third Rock Ventures, a Boston venture capital firm specializing in biotechnology. When he let them know he was looking for a role in biotech, they put him in touch with opportunities at their portfolio companies — including Casma, where he landed.

Casma, which works in manipulating autophagy for therapeutic purposes, needed a doctor with expertise in lysosomal storage diseases. In Ory, they found that expertise combined with clinical development experience and, critically, an interest in moving.

Networking is a key part of Ory’s narrative and is central to most successful career-transition stories. “If they are leaving (academia) of their own volition,” Carl Cohen said, professors land new jobs by learning to make connections.

“Academia is a rather constrained path,” Cohen said. “People don’t pay much attention to networking. On the other hand, once you’re moving into a different domain, it’s all about networking.”

Ory put out feelers through professional contacts to find his way to Casma. In Ryan Potts’ case, after nine years as a professor, the offer came to him from a contact — although at first he didn’t recognize it as such.

When Ray Deshaies, Amgen’s senior vice president of global development and himself a former professor at the California Institute of Technology and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, was working on plans to launch a new program, he sent Potts an email.

Deshaies is well known for inventing PROTACs, or proteolysis-targeting chimeras, double-headed molecules that bind to both a target protein and a ubiquitin ligase that can tag that target for degradation by the proteasome. As PROTACs gain momentum as drug candidates, researchers are exploring ways to use the same bispecific binding approach for a variety of purposes; for example, chimeras that recruit autophagy factors recently were reported. A new program at Amgen called the induced proximity platform, or IPP, would aim at inducing binding or proximity between proteins to achieve these nonproteolysis effects for therapeutic ends.

“Ray sent me an email saying that they’ve got this IPP program, and they’re looking for a leader: ‘Know anybody that might be interested?’ I wrote back … here are a couple of people I’ve interacted with that might fit the bill. And he wrote back immediately, ‘Well, I was really asking if you wanted to do it.’” The conversation went from there.

“I’ve known Ray a while,” said Potts, who as an academic studied proteins that modulate ubiquitin ligases. “His being a thought leader in this field and his passion … was a lot of the driving force that got me interested.”

Without a personal connection or a strong reputation, according to Cohen, that kind of recruitment is uncommon; a typical recruiter, he said, looks first for people already working in industry. After years of leading a lab, he said, “There’s little doubt that you’re scientifically capable … (but) do you have the management, leadership, organizational and interpersonal skills that will allow you to be successful in a business environment? The fact of the matter is most academics do not.”

The culture shift

Recent academia-to-pharma transplants often need time to adjust to the new environment.

Howard Jacob already had left academia to join the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology, a private research institution, when AbbVie approached him with an opportunity. He learned that the company was seeking a genomics expert like himself to head a project collecting one million genomes and mining them for new discoveries.

“I’m toward the end of my career; I wanted to do one more big thing,” Jacob said. “Here was a chance to do the biggest thing … at a scale that I couldn’t have imagined in academia.”

While he found the move to AbbVie exhilarating, a little reminiscent of starting out as a graduate student, he also faced a learning curve. For one thing, there was no such thing as idle discussion of potential experiments. “When I got here, I was creating a little bit of turmoil. I’d go and ask people, you know, bounce ideas off of them — and the next thing I knew, they had done it. So I really needed to work with my leadership team to make sure I wasn’t just creating chaos by asking questions.”

Though his words carry the weight of orders with more people now than when he ran a lab, Jacob said, he also feels a greater sense of accountability to the people who report to him. AbbVie operates by a set of principles called “The Way We Work,” and Jacob’s evaluation and compensation depend in part on how he treats peers and colleagues who report to him. While the qualitative system of metrics gave him pause at first, he now feels that shared ground rules, explicitly outlined, help keep work moving forward.

“That ability to walk in and say, ‘okay, this is going to be a hard conversation … and we all need to be “clear and courageous” so we can solve this problem’— it’s fantastic to be able to do that,” he said, citing an internal catchphrase.

“Some of the complex relationships at an academic medical center are difficult to navigate,” Jacob added delicately. At AbbVie, he has found it easier to resolve conflicts, such as authorship disputes, shared between industry and academia.

An authorship dispute that unfolded while Charlotte Jones–Burton’s mother was dying, along with the difficulty she foresaw in disentangling her own research from her adviser’s, were major factors in the physician–scientist’s decision to take a job at Merck. She said that after arriving at the pharma company, “I didn’t miss the fighting for who’s going to be first author of the paper … (and) the politics of academic medicine that no one ever talks about.”

But the pharmaceutical industry is not without cultural problems common to corporate America, Jones–Burton said. “Thinking about professors and underrepresentation at that level in academia, the same thing happens in the pharmaceutical industry.”

in Pharma to advocate for greater equity within the pharmaceutical workforce

and the patient population it serves.

In 2015, she launched an organization called Women of Color in Pharma to advocate for greater equity within the pharmaceutical workforce and the patient population it serves.

Professors who make the transition from higher up in the academic hierarchy may experience the culture shift as a loss. “I was an endowed chair professor; I had directorship of different parts of the university,” Ory said. “You enjoy, I think, some of the benefits of that status.”

As one of 10 employees at a small biotech company with a more egalitarian culture, Ory missed having an office of his own. “It’s highly collaborative and collegial,” he said. “This is very different from operating as a professor at a university, where maybe you have a laboratory of 20 people and it’s run very top-down. … In some ways, you have to subjugate your ego for the greater good.”

According to Jensen, prominent professors “have postdocs and scientists and lab managers reporting to them and doing their bidding … so the first thing you have to do is make sure that your candidate (if a professor) has a real-world understanding of the cultural difference.”

One important part of fitting into corporate culture is keeping colleagues informed about how projects are coming along.

“If you have your own grants, you have your own lab … there’s not a lot of oversight,” Jacob said. Now, working in a company, he spends a lot of time figuring out how to update colleagues without inundating their inboxes.

Though it took some getting used to, Ory has come to value Casma’s camaraderie. He and others on the company leadership team focus on keeping things egalitarian by sitting intermingled with the rest of the staff in an open-plan office and trusting employees with updates on fundraising and other drivers of the company’s future. He has found that such openness about company finance motivates his employees and increases their sense of ownership of the projects they work on.

Money and resources

Ory, Jacob, Jones–Burton and Potts were all successful grant writers — one must be to make it as a professor — but even for people who are good at landing funding, Ory said, “it’s not something … that you like doing.”

“I don’t mind the grants and the papers and whatnot,” Potts said, “but the cycle times … seem to have been getting longer and longer from the point that you submitted a grant to actually, if you’re lucky, getting the funding.”

being a first year graduate student … it was reinvigorating.”

Resources don’t simply appear in for-profit companies, however; Ory, for example, has learned how to describe the work at his small startup to potential investors to attract their interest and dollars.

At a bigger company, Jacob said, internal funding proposals may be one- to three-slide affairs, submitted once a year for approval, in contrast with the intense and competitive grant application process.

Industry labs are comparatively rich in resources, and that money can buy time as well as reagents. Jones–Burton was delighted with how her work time opened up once she could rely on specialist colleagues for tasks such as making slides and running statistics.

“As junior faculty, I’m writing my own papers, I’m doing my own analyses, I’m doing my own coding,” she said. At a company where separate departments handle those tasks, she found she could focus on her area of true expertise.

And within that area, work proceeds faster. According to Jensen, “There is a real difference in industry and academia in the pace of the work.” While academics can put a primary project on hold to pursue unexpected results or an interesting tangent, “in industry, there are timelines; there are specific goals and objectives that have to be met.”

The greater resources available in industry also can open up more ambitious projects. Jacob, Potts and Ory all said their current projects would have been difficult or impossible in their academic positions.

Instead of collecting genomes in an academic lab, Jacob could use the information AbbVie already was collecting about its patients and help the company build systems to keep track of the data — they’re aiming for a million patient genomes.

Instead of developing promising molecules in an academic lab and trying to get them through a tech transfer process, Potts can roll the business and scientific considerations together.

“This is an initiative that’s been bubbling up for a few years now, where the idea was that you could open up the vast proteome to druggability that has not been accessible before,” Potts said, and he was excited to be part of developing those drugs.

Ory said he no longer feels pressure to fit his ideas into the relatively narrow scope of his previous research; he can work on new disease areas. “Going to a startup gives you a lot of flexibility in terms of thinking about the science … there’s a lot of innovation and creativity that you can have.”

Finally, salaries trend higher in industry. Although compensation for both professors and corporate managers can vary widely depending on institution, precise job title and nonsalary compensation, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median wage for scientific research and development managers — a role that nearly 20,000 people in the U.S. hold — is $176,660. The median salary for postsecondary biological science teachers, including professors at colleges, universities and professional schools, is $97,560.

Missing students

Despite the advantages, former professors also find things to miss about academia. Several expressed nostalgia for teaching, for the students they had worked with and the intellectual atmosphere of a university. Jones–Burton said she also misses caring for patients in the clinic.

When a professor’s career trajectory changes, that means a sudden — and often unplanned — change for their trainees and technicians. The apprenticeship model of science makes trainees highly dependent on professors’ expertise, connections and positive references, although they may also receive support from their programs in transitioning to find new mentors. Staff scientists in academia, whose roles are less temporary by design, also may find themselves in a difficult situation when a professor leaves.

University who recently took a job at Casma Therapeutics.

According to Potts, although his trainees were his primary concern when considering the job move, the shakeup had turned out reasonably well for them by the time he started at Amgen. Some were moving on to their next career stages. “It spurred everyone to take stock,” he said. “After the initial shock wore off for people, it provoked them to look to the next phase of their career.”

Sometimes, trainees have an opportunity to follow their advisers into industry. This seems to happen more often when the PI moves into a leadership role at a large company rather than a small biotech. Two scientists who started out as postdocs in Potts’ academic lab plan to move to Amgen and join the program.

“It’s a real opportunity for them to transition their career paths and start on that in a permanent capacity,” Potts said. “It’s also great for me, because I get two people who are known entities and can understand how we work and establish the lab there … it works out well for everybody.”

When that route is not available — for example, at small companies like Ory’s — departing professors may request that colleagues step in to help mentor their trainees. Ory’s lab at Washington University overlapped with that of his wife, physician–scientist and American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology award winner Jean Schaffer. Since she was already familiar with the people and projects, Schaffer took over the day-to-day management. “That was really, very helpful,” Ory said, adding that most professors do not work so directly with a colleague who can take over and may need to put in more effort recruiting substitute mentors for their trainees.

Changing the mentor on some postdoctoral research awards can be challenging; although he was officially on sabbatical, Ory worked 90% of his time in the new company and spent about 10% of his time advising during the first year of transition. He said, “I wanted to not leave precipitously and leave them in the lurch.”

More movers?

The movement of professors from academia to industry rarely is tracked. Both Cohen and Jensen wondered, though, whether uncertainty brought about by COVID-19 might prompt professors who have the option to seek jobs in industry.

“Because of the turbulence … and the fact that schools may be changing what defines tenure and so forth, (professors) are frustrated at times,” Jensen said. “I’ve had several searches where very senior-level professors have been expressing interest.”

When they do, according to Cohen, they shouldn’t expect an instantaneous transition. “People who are looking to leave academia, for whatever reason, have got their work cut out for them.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Careers

Careers highlights or most popular articles

Sketching, scribbling and scicomm

Graduate student Ari Paiz describes how her love of science and art blend to make her an effective science communicator.

Embrace your neurodivergence and flourish in college

This guide offers practical advice on setting yourself up for success — learn how to leverage campus resources, work with professors and embrace your strengths.

Upcoming opportunities

Apply for the ASBMB Interactive Mentoring Activities for Grantsmanship Enhancement grant writing workshop by April 15.

Quieting the static: Building inclusive STEM classrooms

Christin Monroe, an assistant professor of chemistry at Landmark College, offers practical tips to help educators make their classrooms more accessible to neurodivergent scientists.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.

Exploring lipid metabolism: A journey through time and innovation

Recent lipid metabolism research has unveiled critical insights into lipid–protein interactions, offering potential therapeutic targets for metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases. Check out the latest in lipid science at the ASBMB annual meeting.