What would Julia Child do?

By now, you are familiar with the story. Halfway through spring semester 2020, university administrators inform instructors that the remaining portions of all courses, including labs, must be taught online. A mad scramble ensues to decide on content, delivery and testing, along with a crash course in social media. Professors everywhere ask ourselves, “How can we adapt lab exercises 6-10 to an online format?”

As the fall semester loomed, many of us faced the same challenge: to teach a laboratory course online. As I reflected on my experiences from last spring, I was struck by the similarity of my ad hoc labs to TV cooking shows — you know, the ones where the audience watches as a Julia Child wannabe chops, purees, sautés and mixes. There is never enough time for something to bake or roast, so a perfect example of the final product is hidden away to be whipped out at the end of the show, displaying for the viewers how the manipulations they just witnessed ought to turn out.

To an uncomfortable degree, the data we hand out to students in some online labs seem to be the virtual equivalent of a cooking show’s final product.

I asked myself to what degree spring semester’s extemporized online labs could be described as experiential. What sets a lab course apart from a lecture or demonstration? It couldn’t simply be the direct interpersonal contact or participation in physical manipulations. What key element was missing? It soon struck me that separating the different steps involved in planning, preparing and performing an experiment had severed the cause–effect relationships they were intended to illuminate.

As a postdoc, I once made cookies for the lab using baking soda rather than baking powder, with embarrassing and distasteful results. My failure to apprehend that these ingredients were not interchangeable resulted in personal consequences that had a more lasting impact than if someone simply had corrected me as I reached for the wrong container.

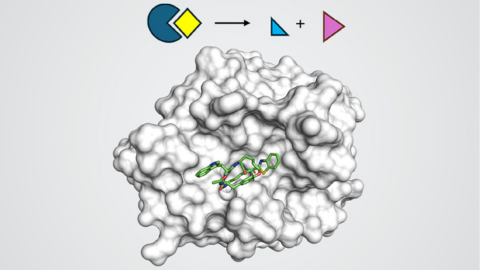

Consider a class asked to devise a protocol for determining kinetic parameters for an enzyme. The instructor provides the students with a range into which the parameters will fall. One student might select concentrations for the variable substrate that all fall in the saturating range. Normally, upon executing their protocol in person, this student would be confronted by the realization that something was amiss. After reflection and discussion, they could amend the protocol and try again.

In last spring’s online environment, however, I would have given the student written feedback on their protocol but then handed them authentic data collected the previous semester by students who used appropriate substrate concentrations. By so doing, I deprived my online students of the vivid, consequential necessity of figuring out what went wrong — and the direct, tangible affirmation of generating viable results.

More than the lack of sensory and mechanical experiences of processes, such as pipetting, weighing, pH-ing and centrifuging, I would argue that our tendency to compartmentalize individual steps, thereby severing the causal connections between student decisions and future outcomes, represents the most important pitfall in online laboratories. In other words, it is not the analysis of data that constitutes the cornerstone of experiential learning; it is the dynamic, interactive process of decision, outcome and revision leading to reliable, interpretable data.

So how can we design practical online labs that enable students to experience the consequential, causal links characteristic of our best in-person labs? In a limited number of cases, manipulations planned by the students can be executed by proxy, by the instructor or teaching assistants. Cloning, for example, probably can be done this way; we could order primers designed by the students from a vendor, run PCR reactions in parallel and send the images of the resulting agarose gels to the students. We then could prepare ligation mixtures and plate the mixtures according to the students’ instructions, with the resulting petri dishes photographed and forwarded to them.

In many other cases, it should be possible to provide virtual results. Given the protocol for generating a standard curve for, say, a bicinchoninic acid assay, the instructor can examine one of the standard curves on file and report back to the students the absorbances obtained. Similarly, enzyme kinetic data can be generated from known Vmax and Km values.

The extra burden on faculty, teaching assistants and staff and the back-and-forth exchanges of instructions, data and feedback between instructors and students likely mean that online versions of these labs will require more time to complete than the in-person versions. Moreover, not all labs can adapt to such a model. However, I would argue that even if we must reduce the total number of topics or techniques covered during a semester, the experiential richness of causally connected online labs will make them well worth the effort.

About the experiment

The photos above depict an experiment exploring why a particular restriction fragment of phage lambda DNA is resistant to cloning in E. coli. For example, does the segment encode something toxic to the bacteria? The instructor, Tim Larson, screened smaller pieces of the restriction fragment, generated by polymerase chain reaction, including some with mutations in putative promoter regions. The DNA fragments were incubated with a plasmid vector along with DNA ligase, and the contents of the ligation reaction mixed with competent E. coli. During this process, only some of the bacteria took up the plasmid vector, and only a portion of these plasmids contained the piece of DNA the instructors wished to clone, called an insert. To select for those few E. coli that took up the plasmid, and to then determine which ones contained an insert, the bacteria were plated onto agar containing antibiotics as well as an inducer known as IPTG and a reporter substrate known as X-Gal. Only those E. coli that took up the plasmid would grow and form colonies on the plate. Among these, those lacking the insert appeared blue on the IPTG/X-Gal plate. Those containing the insert appeared white.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Careers

Careers highlights or most popular articles

Engineering the future with synthetic biology

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on synthetic biology, featuring applications to better human and environmental health.

Host vs. pathogen and the molecular arms race

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on host–pathogen interactions, to be held Sunday, April 13 at 1:50 p.m.

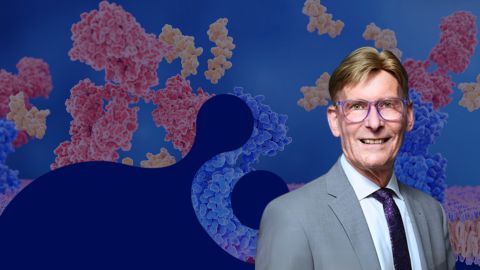

Richard Silverman to speak at ASBMB 2025

Richard Silverman and Melissa Moore are the featured speakers at the ASBMB annual meeting to be held April 12-15 in Chicago.

Women’s History Month: Educating and inspiring generations

Through early classroom experiences, undergraduate education and advanced research training, women leaders are shaping a more inclusive and supportive scientific community.

Upcoming opportunities

Register for the May 14 ASBMB Breakthroughs webinar on biosynthesis and regulation of plant phenolic compounds.

Upcoming opportunities

Save the date for ASBMB's virtual meeting on nucleophilic proteases. Reminder: Get your ticket for #ASBMB25's closing reception at the Griffin Museum of Science and Industry before it sells out!