Addressing accessibility in STEM

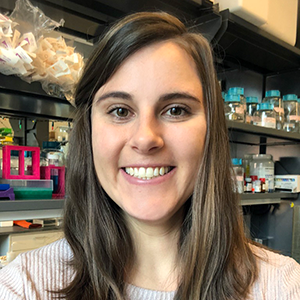

As a second-year graduate student at the Baylor College of Medicine in the cancer and cell biology program, Alyssa Paparella has been navigating research and the challenges it presents. As a disabled scientist, she also has had to advocate for herself to get the accommodations she needs to be successful and has used her experiences to be a vocal advocate for disabled members of the STEM community.

Paperella's passion for science started in high school — she wanted to understand what was wrong with her body and why it wasn’t cooperating the way it should. She started to read about science topics and found a doctor that would talk about the details with her and encouraged her love of science.

Paparella then attended Sarah Lawrence College and said that was the environment that made her a scientist. She recalled not knowing how to use a microscope during a genetics laboratory, despite the fact that everyone else seemed to know what they were doing. She said it was overwhelming, but her professor came over and showed her how to use one without judgment. He would serve as a mentor and resource for her during subsequent courses as well.

“That was the moment I really knew I could be a scientist,” she said. “I’d struggled with my own ability beforehand, but my research and his mentorship changed that.”

Finding a fit

Paparella said it can be challenging for those with disabilities to find both a lab space and a mentor that is accessible and accommodating. University accessibility/accommodations offices are supposed to offer support, but Paparella said they can sometimes seem more like gatekeepers than allies.

It took her close to a year after starting graduate school to get the accommodations she needed in the classroom and, although she tried to be an advocate for herself and let professors know what she needed, not all were receptive. Paparella describes herself as having an invisible disability, meaning you may not immediately identify her as disabled just by talking or meeting with her. Yet she said she oftentimes can see a shift in potential mentors or colleagues once they are informed that she is disabled.

“There’s an assumption in STEM that everyone is able-bodied and healthy, but that’s not always the case,” she said. “It’s an issue for the entire disability community independent of discipline.”

She shared the story of a principal investigator with whom she was particularly excited to rotate after starting graduate school. Paparella qualified for and was awarded a grant through the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program, so she was able to bring her own funding into whatever lab she joined. Paparella said that she had a wonderful meeting with this PI and that they even came up with a project. After the meeting, she followed up and also sent a list of the disability accommodations she would need to be successful. The next day, she got an email saying the rotation wasn’t going to work out.

“Accommodations are a part of who I am, and it’s not a limitation. It’s just giving me equal access to the tools for success,” she said. “Stigma and internalized ableism are preventing conversations about how to be more accommodating and supportive.”

Building awareness and a supportive community

Paparella told me that she wants to raise awareness about the challenges disabled individuals face in STEM and demystify the experience for those interested in a similar career path. She runs a Twitter account (@DisabledStem) with which she shares her own experiences and amplifies the voices of other disabled people.

Last summer, she also created a mentorship program and made 45 mentor–mentee matches between disabled individuals in STEM throughout all stages of careers. Part of the motivation behind starting this program was to have more tailored advice and mentorship, she said.

While her undergraduate genetics professor was extremely supportive, Paparella told me, he didn’t have experience navigating science with disabilities and couldn’t always provide the advice she needed. (When should she disclose her disability? How do you find and navigate the office of accommodations?) By connecting people who might have similar experiences, she said, she hopes to be able to provide answers to these questions.

“It was a bit overwhelming and difficult starting the program,” she said. “But I wanted to create a space where we could provide advice and connect with each other on a more intimate scale to help retention in the long term and see that others have been successful.”

Paparella also engages with allies aren't disabled but who want to help create a more inclusive space. She gives tips on how to engage someone with a disability and other advice for how to make a physical lab space more accessible, how to mentor, and how language changes can make a difference.

“Including allies is important not only to change their perspective and increase awareness, but also their voice is important to progress overall,” she said.

Making STEM more accessible

Science and academia have strides to make to create a more inclusive environment. Specifically, Paparella said, lab spaces not being accessible is a huge program.

“Universal design principles (intended to make spaces accessible to all) should be used to develop lab spaces instead of giving someone different treatment or making an exception on a case-by-case basis,” she said.

She credits the work of Joey Ramp with increasing awareness about service dogs in the lab (which has also been featured in the past by ASBMB Today).

Another issue major issue is time.

“Finding the time within academia to go to doctor’s appointments or physical therapy can be hard since they tend to be the same schedules as classes and lab,” Paparella said. “Physical therapy three times a week may be critical to your health, but your PI may expect you to be there 9 to 5 as well.”

Getting the care you need can be challenging, especially if a PI doesn’t understand the necessity of the appointments or is strict about lab schedules. Additionally, medical procedures or condition flare-ups can prevent work for extended periods of time and aren’t always predictable.

Paparella said that more people need to start having the conversation about accessibility in STEM.

“Overall, academia needs more training on how to navigate these issues and how to provide support,” she said. “It’s not something we're currently talking about and (administrators and PIs) don’t know how to talk about it because it feels awkward for them.”

Also, she said, institutions need to invest in accessibility, which is easier said than done. Making infrastructure changes to labs or classrooms is costly. Paparella said she thinks there should be specific funding lines that could be used to assess and correct issues related to accessibility on campuses.

A related issue concerns relocation. Many tell you relocation (for grad school, a postdoc or a job) is an inherent and necessary partner to success. Moving frequently is destabilizing for anyone. But it's worse when it means that you won't be close to your team of doctors or other providers.

“We need a shift toward a more inclusive environment,” Paparella said. “There are so many amazing scholars who we aren’t hearing their voices because of how exclusive academia is. We are losing out on the future.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Careers

Careers highlights or most popular articles

Upcoming opportunities

Friendly reminder: May 12 is the early registration and oral abstract deadline for ASBMB's meeting on O-GlcNAcylation in health and disease.

Sketching, scribbling and scicomm

Graduate student Ari Paiz describes how her love of science and art blend to make her an effective science communicator.

Embrace your neurodivergence and flourish in college

This guide offers practical advice on setting yourself up for success — learn how to leverage campus resources, work with professors and embrace your strengths.

Upcoming opportunities

Apply for the ASBMB Interactive Mentoring Activities for Grantsmanship Enhancement grant writing workshop by April 15.

Quieting the static: Building inclusive STEM classrooms

Christin Monroe, an assistant professor of chemistry at Landmark College, offers practical tips to help educators make their classrooms more accessible to neurodivergent scientists.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.