Acquiring new skills and growing networks

On the seventh floor of the Biosciences Building at The Ohio State University, Pablo Galaz–Davison practices assembling and breaking down a centrifugal force microscope. Galaz–Davison, a second-year Ph.D. student at the Universidad de Chile, is learning the intricacies of this piece of equipment and its many applications in mapping the mechanical properties of single molecules while he visits the laboratory of Marcos Sotomayor, a structural biologist specializing in protein structures and molecular dynamics.

Galaz–Davison’s three-month stay in Sotomayor’s lab has been made possible by the Promoting Research Opportunities for Latin American Biochemists, or PROLAB, program. Over the past seven years, the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, the Pan-American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and the International Union for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology have given 60 young biochemists travel awards to advance their research by working directly with collaborators at labs in the United States and Canada.

In 2017, PROLAB gave travel grants to seven Ph.D. students, two postdoctoral fellows and one assistant professor; these recipients are from Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, Brazil, Portugal and Spain (see box).According to former ASBMB President Judith Bond, who has served on the awards committee for the program since its inception in 2010, the idea for PROLAB emerged after she traveled to the 2005 PABMB annual meeting in Buenos Aires.

“When I was there, I was really impressed with the training and quality of the graduate students and the postdocs who were presenting,” Bond said. “There were some (lab facilities) that were very well-equipped but many places that weren’t, and there was a desire to make connections with labs in the United States where they could do some special types of procedures or use some type of instrumentation during their training. I came back from that meeting with the idea of trying to forge some relationship between Latin America and the United States.”

Bond’s idea was supported by former ASBMB Presidents Susan Taylor, Heidi Hamm and Bettie Sue Masters, who collectively submitted a proposal to the ASBMB Council to provide $75,000 for the program over three years.

“Someplace along here, the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology decided this was a really good idea and that they would also kick in some funds to support the program,” Bond said. This doubled the total funding for PROLAB to $50,000 each year for the first three years.

According to Jose Sotelo–Silveira, the general secretary of the PABMB and a member of the awards committee, PROLAB “generates a lot of networking and connections, which are essential for building a healthy scientific community in the south linked to the one in the north.”

That belief is shared by the PABMB’s leadership, including Hugo Maccioni, the society’s chairman, who said, “We believe that it is extremely useful for young investigators from countries affiliated with PABMB to update themselves in state-of-the-art technologies in the laboratories of people affiliated with ASBMB, and establish productive relations with them.”

Getting the program off the ground ultimately took about five years, Bond said. The first awards were given out in 2011 to nine biochemists from Brazil, Argentina and Chile.

Physics and folding

Galaz–Davison’s primary investigator, Cesar Antonio Ramirez–Sarmiento, was among the second cohort of scientists to receive PROLAB awards, back in 2012. At that time, Ramirez–Sarmiento was a graduate student at the Universidad de Chile using biophysics principles to explore whether bacterial enzymes made up of multiple polypeptide chains need to finish folding before becoming fully functional. “I was trying to understand whether they fold first and then they bind, or whether they bind and fold at the same time,” he said.

A few months after applying for an award at the suggestion of his primary investigator, Jorge Babul, then the chairman of the PABMB, Ramirez–Sarmiento was getting to work at the University of California, San Diego, in the lab of Elizabeth Komives, whose expertise includes the biophysics governing protein–protein interactions mediated by nonglobular proteins.

“I got access to all of the instruments I needed for doing that kind of research. I didn’t have them in my country,” Ramirez–Sarmiento said. “I was able to go for three months, and I did, I will say, half of my (Ph.D.) research over there. It was great.”

At the time, Komives’ lab was adjacent to the Center for Theoretical Biological Physics, now located at Rice University, which allowed Ramirez–Sarmiento to learn computational techniques he hadn’t previously encountered. “I ended up doing both computational work and experimental work, and it threw me into this idea of doing interdisciplinary research in my (own) lab,” he said.

After completing his stint at UCSD, Ramirez–Sarmiento finished his Ph.D. and a postdoctoral fellowship at the Universidad de Chile. He then took a faculty position at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. In 2016, Ramirez–Sarmiento received a second PROLAB award and spent three months at the Ohio State lab of Irina Artsimovitch, who studies the mechanism and regulation of RNA-chain synthesis in bacteria. While at Ohio State, Ramirez–Sarmiento also met Sotomayor, a fellow Chilean and biochemist in whose lab Galaz–Davison now works.

Affordable revolutions

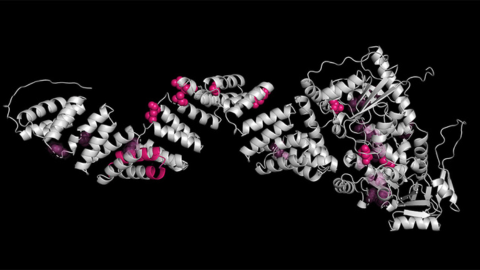

Ramirez–Sarmiento’s current research involves thermodynamically characterizing RfaH, a metamorphic protein that has similar molecular mechanisms to prions, as well as an enzyme that degrades polyethylene terephthalate, or PET, the clear plastic found in water bottles. Galaz–Davison, who applied to the PROLAB program at Ramirez–Sarmiento’s suggestion, is involved in both of these research projects, which employ X-ray crystallography, computer simulations and the highly focused laser beams of optical tweezers to characterize biological features of both molecules.

One of Galaz–Davison’s goals for his PROLAB experience was to learn how to set up and break down a centrifugal force microscope, a type of atomic-force microscope that measures the mechanical properties of single molecules by applying a uniform centrifugal force to an orbiting sample. While many recipients spend their time in labs outfitted with extremely high-end equipment, the CFM is actually more affordable than its counterpart in Chile.

“The thing is, it’s cheap,” Galaz–Davison said. “The optical tweezers that we have access to in Chile cost $70,000.” The CFM, which does essentially the same thing, costs about $5,000, he said.

After learning the intricacies of the instrument, Galaz–Davison set about applying it to RfaH while simultaneously using X-ray crystallography to determine the atomic structure of the PET-degrading enzyme. “We’re now finishing with computational work using molecular dynamics on this enzyme and trying to round up everything we’ve got on this project to try to publish a paper as soon as possible, which is thanks to this, because we didn’t have a structure (defined for the molecule),” he said.

In his remaining time at Ohio State, he plans to finish characterizing the kinetic properties of how the PET-degrading enzyme acts on PET.

Branching into biochem

Beyond access to unfamiliar equipment and the scientists who use it, PROLAB awardees often use their time abroad to explore a new discipline that intersects with their own. At Columbia University, Tiago Figueira is complementing his knowledge of biophysics with a gamut of biochemical lab techniques.

Figueira, now in the final year of his doctoral research at the Universidade de Lisboa Instituto de Medicina Molecular, arrived at Columbia on April 28 for a six-month stint in the lab of Anne Moscona and Matteo Porotto.

“Through biophysics, I’ve entered the world of virology,” said Figueira, whose work began with HIV antivirals and soon expanded to include similar compounds effective against measles and influenza viruses.

“If you do biophysics for a living, you are very good at doing spectroscopy analyses and characterizing molecules, but you may lose on the big part of cell biology and molecular biology and miss the opportunity of correlating both fields,” he said.

By taking this approach, Figueira was able to analyze the effects of proteins and mutations on viral entry, which expanded his appreciation for the field as a whole. “I always thought techniques (that) are routine for most molecular biologists…were really my Achilles heel, and here I do them every day.”

Figueira was surprised that he was able to get to know his professors outside of the laboratory. “When you come to a foreign lab, you think, ‘My life is going to be mostly professional.’ Right?” he said.

“I had the opportunity of having my girlfriend visit for two weeks,” he said. “At the end of the first week, we were walking down the street and came across one of my supervisors, Professor Anne Moscona. She was so happy to see us both together and she was so happy to meet her that in the following days we ended up having lunch or dinner together almost every day.

“It was so good to have their personal support and even make my girlfriend feel that I’m in good hands. For me, that was really memorable, and it connects both my personal and working life.”

Shorter stays

Meritxell Jodar Bifet, an assistant professor at the Universitat de Barcelona, recently finished her PROLAB stay in Julia Salzman’s lab at Stanford University. Jodar is investigating whether RNA in sperm may be a biomarker of male fertility as well as its potential role in early embryogenesis and epigenetic inheritance.

Her teaching responsibilities in Barcelona gave Jodar only six weeks, from July 16 to Aug. 31, to learn the computational and biochemical techniques she needed to begin studying the role of circular RNA in sperm cells. She learned how to enrich sperm samples for circular RNA, which involved treating them with RNaseR, a ribonuclease that digests nearly all linear RNA.

She also had the opportunity to use a new algorithm known as KNIFE that Salzman’s lab designed to increase the sensitivity and specificity of circular RNA detection, which is useful for assessing the total number of circular-RNA strands in a sample. “The circular RNA molecules are much more stable than regular RNAs,” she said. “This suggests to me that it could be a good strategy to provide information from the sperm to the oocyte because traveling from the sperm to the oocyte…is a long trip, and maybe the circular RNAs will be the best vehicle to transmit paternal information to the new individual.”

Jodar now plans to examine the roles that these circular RNA play in male fertility, early embryogenesis and transmitting paternal acquired traits to progeny.

“I hope that that we can continue this collaboration within the University of Barcelona and Stanford University in order to discover the real function of the circular RNAs in the sperm,” she said.

Countries of origin

While the majority of the travel awards go to students from universities in Central and South America, applications also are considered for students from Portugal and Spain. According to former ASBMB President Judith Bond, this inclusion came when the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, which contributes half of the $50,000 meted out to 10 applicants each year, joined with the ASBMB to support the program.

Listed here are the countries of origin of the 60 PROLAB recicipients since the program started in 2011.

Argentina – 17

Brazil – 9

Chile – 16

Columbia – 1

Cuba – 1

Mexico – 2

Peru – 1

Portugal – 4

Spain – 6

Uruguay – 3

Hippocampal tangle

While some of this year’s recipients are in the midst of their visits and others have returned home, Rafaella Araújo Gonçalves da Silva plans to begin her fellowship in the lab of Paul Fraser at the University of Toronto’s Tanz Centre for Research in Neurodegenerative Diseases by the end of October. A Ph.D. student at the Instituto de Bioquímica Médica at Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Gonçalves is investigating the molecular mechanisms in the brain’s hypothalamus underlying the connections between Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes.

“Historically, people think about Alzheimer’s as a disease of memory, so they look at the hippocampus and cortex,” she said. “Hypothalamal dysfunction could be happening in Alzheimer’s disease, which would explain this correlation with metabolic dysregulation in diabetes.”

Gonçalves’ previous research has examined the ability of intracerebroventricular infusion of amyloid beta-oligomers in wild-type mice to trigger hypothalamic alterations and metabolic dysregulation. She plans to expand her research to include a variety of mouse models for Alzheimer’s disease available in Fraser’s lab.

One of those mouse models is designed to express the human tau protein, which becomes abnormally hyperphosphorylated and aggregates into neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease.

“What we want to do now is see if the same hypothalamic and metabolic alterations we saw in our animals are related to tau hyperphosphorylation in this model in Paul Fraser’s lab,” said Gonçalves, who is planning to work in the lab for four months.

“They also have a lot of equipment and reagents, and it’s so much easier to buy something there,” she said. “Here in Brazil, if you buy an antibody, it’s going to take three months or more to get to your bench, and there, I can buy it one day and it’s going to be there on my bench the next day.”

Whether the young scientists visit for six weeks or six months, the networks the PROLAB recipients build have a lasting impact on their careers that can prove more valuable than technical experience or exposure to high-end equipment.

Barbara Gordon, executive director of the ASBMB, said the program is funded year-to-year and the society intends to fund it for the foreseeable future. “The PROLAB program has had a monumental effect on the careers of its recipients,” she said. “We hope that it can continue to do so for as long as possible.”

In his lab in Chile, Ramirez–Sarmiento is drawing up research proposals that include Komives and the other collaborators he has gained over the years. “You keep these people that you know through this program forever,” he said. “You think about them for every research endeavor that you can have.”

2017 PROLAB recipients

|

Julia Roulet, Ph.D. student, Argentina Institution: Instituto de Biología Molecular y Celular de Rosario Host lab: University of California San Diego, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry; Michael Burkart Research: Developing algae as a platform for high-valued molecules production. |

|

Gabriel Oka, postdoctoral fellow, Brazil Institution: Universidade de São Paulo Host lab: Howard Hughes Medical Institute, California Institute of Technology; Grant Jensen Research: Pseudomonas aeruginosa’s use of toxins via the bacterial type-IV secretion system as a defense mechanism |

|

Germán Michelis, Ph.D. student, Argentina Institution: Instituto de Investigaciones Bioquímicas de Bahía Blanca Host lab: National Institutes of Health National Eye Institute; Patricia Becerra and T. Michael Redmond Research: Exploring the effects of pigmented epithelium-derived factor on cultured retinal neurons |

|

Martina Lazarro, Ph.D. student, Argentina Institution: Instituto de Biología Molecular y Celular de Rosario Host lab: Washington University in St Louis; Mario Feldman Research: The role of the type-VI secretion system of Serratia marcescens in bacterial interactions; intracellular traffic of Serratia in eukaryotic cell system |

|

Mauricio Mastrogiovanni, Ph.D. student, Uruguay Institution: Universidad de la República Host lab: University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Pharmacology and Chemical Biology; Francisco Schopfer Research: Tyrosine and fatty acid oxidation and nitration in biomembranes |

|

Maximiliano Vazquez, Ph.D. student, Argentina Institution: Universidad Nacional de Córdoba Host lab: University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Pharmacology and Chemical Biology; Bruce Freeman |

|

Tiago Figueira, Ph.D. student, Portugal Institution: Instituto de Medicina Molecular, Universidade de Lisboa Host lab: Columbia University, College of Physicians and Surgeons; Anne Moscona and Matteo PorottoResearch: The biophysics of viral entry processes |

|

Rafaella Araújo Gonçalves da Silva, Ph.D. student, Brazil Institution: Instituto de Bioquímica Médica, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Host lab: Tanz Centre for Research in Neurodegenerative Diseases, University of Toronto; Paul Fraser Research: The role of hyperphosphorylation of tau protein in hypothalamic and metabolic alterations related to Alzheimer’s disease |

|

Pablo Galaz-Davison, Ph.D. student, Chile Institution: Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacéuticas, Universidad de Chile Host lab: The Ohio State University, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry; Marcos Sotomayor Research: Characterizing the structural and thermal properties of RfaH and PET-degrading enzyme |

|

Meritxell Jodar Bifet, assistant professor, Spain Institution: Universidad de Barcelona Host lab: Stanford University School of Medicine, Julia Salzman Research: The potential of circular RNA in male sperm as clinical biomarker of male infertility and its role in early embryogenesis and epigenetic inheritance. |

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Careers

Careers highlights or most popular articles

Upcoming opportunities

Friendly reminder: May 12 is the early registration and oral abstract deadline for ASBMB's meeting on O-GlcNAcylation in health and disease.

Sketching, scribbling and scicomm

Graduate student Ari Paiz describes how her love of science and art blend to make her an effective science communicator.

Embrace your neurodivergence and flourish in college

This guide offers practical advice on setting yourself up for success — learn how to leverage campus resources, work with professors and embrace your strengths.

Upcoming opportunities

Apply for the ASBMB Interactive Mentoring Activities for Grantsmanship Enhancement grant writing workshop by April 15.

Quieting the static: Building inclusive STEM classrooms

Christin Monroe, an assistant professor of chemistry at Landmark College, offers practical tips to help educators make their classrooms more accessible to neurodivergent scientists.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.