Variety in academia

By far my favorite part of writing the academic careers column for ASBMB Today over the past two years has been interviewing people. I still get a little nervous right before, when the phone is ringing, but I love all the conversations. It surprises me how much I love the interviews, because I think of myself as an introvert, but getting to know people, even if only for 15 minutes or an hour, has been rewarding and enlightening.

I love hearing everyone’s unique story and point of view. I find that in every interview I genuinely do not know what people’s answers will be to my questions. When I go in with assumptions about what people probably will say or think, I am almost always wrong. While sometimes that leads to me pausing awkwardly and self-consciously while I think of how to follow up, I love being truly surprised by people’s thoughts and experiences. It feels like it’s opening my world, and I hope I’ve been able to convey that in my articles.

Besides being mind-opening, the unexpected answers and stories I hear during interviews also can be comforting and encouraging. Sometimes I feel like I don’t fit the mold of a good academic, but after all these interviews, it seems to me that there is perhaps no mold. Instead, there is a truly wide range of experiences, opinions and personalities — more than I expected — and science is better for that.

The three takeaways that I want to share are:

-

No two people’s paths are the same.

-

Even two jobs with the same job title can be very different.

-

There are lots of academic careers besides professor.

No two paths are the same

I know when I interview professors there is certainly survivorship bias making it look like a more accepting field than it is. If you want to know what it’s like to try to be an actor in Hollywood, for example, it may be inspiring to read about Jennifer Aniston getting discovered and cast in “Friends.” But it may be more accurate to interview any of the thousands of actors who are still currently waiting tables while they wait to be discovered. And I’ve been interviewing a lot of Anistons.

A friend of mine on a search committee for a small school said they recently got more than 200 applicants for a professor job opening, making each candidate’s chance of getting hired 0.5%, and I’ve been largely, though not exclusively, interviewing those who got those jobs.

Even with this bias in mind, I’ve been happily surprised and encouraged at how different each person is and how different their individual career trajectories are. Everyone has their own ideas about research and about their jobs. They all have different strengths and weaknesses, different favorite parts and least favorite parts of the job. They each found their job in different ways.

No one’s career is really like anyone else’s.

I’ve spoken with people who have done things I didn’t think were possible, like moving from industry to a teaching job, as Cheryl Bailey did when she moved from Promega to Midland University. (She’s now a dean at Mount Mary University in Wisconsin.) Or moving almost straight from a Ph.D. to a professorship, like Sam Sternberg did when he started his lab at Columbia University.

Each professor builds their lab slightly differently too: Some PIs want someone who has expertise or knowledge they need; others want only enthusiasm.

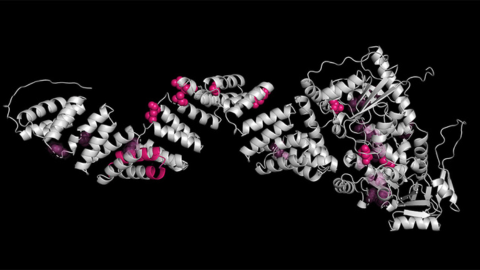

The variety of direct and circuitous paths, paths that ended up where people expected and paths that led to unforeseen changes, are good reminders that there isn’t necessarily a standard way to make a career in academia. You might end up working on something because of a simple but inspirational interaction, as in Manajit Hayer–Hartl’s case: A colleague told her over the phone that the problem of synthesizing rubisco outside of chloroplasts had not been solved, so she set out to do it, and did, winning the ASBMB–Merck Award for it!

Or you might start out wanting to do only research, thinking that teaching is a chore, only to discover along the way that teaching is your true passion, as did Ruby Broadway at Dillard University. She now devotes most of her time to student programs at the university, something she didn’t expect at the beginning.

There is variability within jobs with the same title

I’ve also been happily surprised to find how many different niches there are in any given job in academia. Even being a professor varies quite a bit from institution to institution, and there are many different types of professor positions with different responsibilities, including differing amounts of teaching and grant writing.

Even among the professors at primarily undergraduate institutions whom I interviewed last year, each had a different job with different amounts of teaching, which meant each school was seeking something different. Jen Schroeder at Young Harris College, for example, focuses almost entirely on teaching and campus life, while Alex Purdy at Amherst devotes more of her time to research. This was reflected in the job search process: At Young Harris, teaching experience is weighed more heavily in the application process, while at Amherst the search committee looked more closely at the research plan and required less teaching experience.

Positions such as technician, research associate and research specialist vary dramatically between institutions too. They can vary even between labs at the same institution, as Minakshi Poddar experienced in her career at the University of Pittsburgh. She has been a research specialist in three different labs and found each to be a different environment and work style.

A fascinating discovery came from interviewing many people on a given topic, such as working at a PUI, how PIs hire postdocs, leaving and returning to the academy, or how PIs start their own labs. The people I spoke with had such an assortment of experiences that it often was hard to find commonality or consensus for the articles. This was really refreshing and encouraging because to me it means there are a lot of different niches out there, and it’s possible to find yours. If one institution or job isn’t a good fit, another might be perfect.

There are so many other jobs in academia besides professor

People are drawn to different aspects of academia, and people have different skills and strengths and weaknesses. Some love the teaching and school community, so they do just a bit of research. Some love the research and teach if they have to. Some love writing grants and getting their ideas down on paper but hate wet lab work. Others love seeing the raw results in lab, but writing grants is a drag for them. Some love being in charge of a lab, and others prefer to let someone else make the big decisions.

This is reflected in the many different kinds of workers in academia, including professors, technicians, lab managers, research specialists, core managers, senior research scientists, associate scientists and lecturers. There isn’t just one mold that everyone must fit.

Over the past two years of covering academic careers, I’ve been happy to discover that your career truly can be your own.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Careers

Careers highlights or most popular articles

Upcoming opportunities

Friendly reminder: May 12 is the early registration and oral abstract deadline for ASBMB's meeting on O-GlcNAcylation in health and disease.

Sketching, scribbling and scicomm

Graduate student Ari Paiz describes how her love of science and art blend to make her an effective science communicator.

Embrace your neurodivergence and flourish in college

This guide offers practical advice on setting yourself up for success — learn how to leverage campus resources, work with professors and embrace your strengths.

Upcoming opportunities

Apply for the ASBMB Interactive Mentoring Activities for Grantsmanship Enhancement grant writing workshop by April 15.

Quieting the static: Building inclusive STEM classrooms

Christin Monroe, an assistant professor of chemistry at Landmark College, offers practical tips to help educators make their classrooms more accessible to neurodivergent scientists.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.