'I wanted to give students a sense of the whole process'

Laboratory techniques are critical skills for anyone hoping to pursue a career in research. Most undergraduate degree programs include lab courses as part of their curriculum to teach these valuable skills — but these courses are extremely varied in their scope and effectiveness.

Joe Chihade, professor of chemistry at Carleton College in Minnesota, has been developing biochemistry lab courses for undergrads for almost two decades and has seen what works and what doesn’t. This week, he’s giving his tips and tricks for designing an effective lab course.

Course content

Chihade was first tasked with designing a biochemistry lab course to accompany the biochemistry lecture course in the chemistry department at Carleton. The goal was to expose students to basic biochemical techniques, such as protein purification and DNA manipulation.

“I was interested in demonstrating the process of doing biochemical research, all of the different techniques, and all of the different ways you can think about research,” Chihade said. “I wanted to give students a sense of the whole process and all of the different components involved.”

Chihade recommends that courses be designed as project-based labs. Instead of conducting unrelated individual experiments during each lab, he recommends having a central project or theme that runs through the whole course. This will help students think about the research process as a whole, while also gaining exposure to biochemical techniques. A project-based approach is also more representative of real-world research.

Chihade’s students come up with a hypothesis at some point in the course and then test that hypothesis during their own experiments. In this way, they become accustomed to thinking about their research in the context of a specific hypothesis and get practice interpreting results in that framework.

Chihade also said that, when designing specific experiments, it is important to include positive controls. He tries to make sure all of his experiments include at least one sample that is guaranteed to work if the technique is done correctly.

“The students are often learning techniques for the first time, so they need to see if something didn’t work because that is the true experimental result or because the technique wasn’t done properly,” he said. “Doing something wrong is part of the learning process, and being able to separate that from testing the hypothesis is important in this type of learning environment.”

There are many ways a lab course can be designed, and the specific projects and techniques included will vary. Chihade encourages course designers to consider how many techniques will be covered in a lab and to what level of detail. To figure this out, Chihade recommended that course designers think about the overall goals of the course.

“Is it important to expose the students to a few techniques deeply or to a broader set of fundamental techniques?” he said. “I don’t think there’s a right choice, but thinking about that decision and what you’re giving up with each choice is important as you are starting the course design.”

Encouraging engagement

Chihade said it is important to teach fundamental techniques by choosing experiments that students would be engaged with or interested in. For example, when the COVID-19 pandemic started and his lab course pivoted to a remote format, Chihade re-structured the course entirely to make it more topical.

“Before the pandemic, the lab course was focused on working with pretty basic enzymes,” he said. “That seemed inappropriate in the middle of the pandemic with all the research coming out incredibly quickly about COVID-19, so we transitioned.”

Chihade acquired the plasmids for two SARS-CoV-2 proteins. He had his students design primers for protein expression and then conducted the lab techniques himself, presenting the results to his students for them to analyze and interpret remotely.

Chihade’s choice to update his course material is noteworthy. When students are more connected to the lab material, they’re more likely to remember the lessons they learned.

Chihade said one way that course designers can make their lab courses more engaging is by incorporating elements of their own research. There is a general trend in teaching to incorporate course-based undergraduate research experiences, or CUREs. But, Chihade has a word of warning for this approach.

“There’s a trap one can fall into when using a CURE-based approach to develop a lab course,” Chihade said. “Doing research that’s so tightly tied to the faculty member’s research may mean it’s more focused on a relatively small set of experimental techniques or may not always have straightforward positive controls.”

Overall, Chihade said, there isn’t a wrong approach to take, and he advises course designers to consider the goals of the lab course as well as their personal interests when designing an effective and engaging lab course for undergrads.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Careers

Careers highlights or most popular articles

Upcoming opportunities

Calling all biochemistry and molecular biology educators! Share your teaching experiences and insights in ASBMB Today’s essay series. Submit your essay or pitch by Jan. 15, 2026.

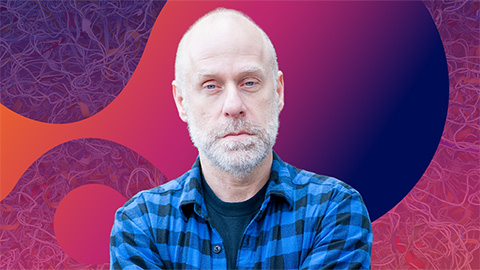

Mapping proteins, one side chain at a time

Roland Dunbrack Jr. will receive the ASBMB DeLano Award for Computational Biosciences at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Exploring the link between lipids and longevity

Meng Wang will present her work on metabolism and aging at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Upcoming opportunities

Calling all biochemistry and molecular biology educators! Share your teaching experiences and insights in ASBMB Today’s essay series. Submit your essay or pitch by Jan. 15, 2026.

Defining a ‘crucial gatekeeper’ of lipid metabolism

George Carman receives the Herbert Tabor Research Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Building the blueprint to block HIV

Wesley Sundquist will present his work on the HIV capsid and revolutionary drug, Lenacapavir, at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, in Maryland.