Meet Efraín E. Rivera–Serrano

For this week’s column, I talked to Efraín E. Rivera–Serrano, a virologist and science communicator. He shared how he went from research associate at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to having several online science communication jobs.

While growing up rural Puerto Rico, he was surrounded by animals. Rivera–Serrano thought he was going to be a vet. While attending the Pontifical Catholic University of Puerto Rico, he did a microbiology summer internship. After the internship, he took a botany class and realized he wanted to go to graduate school after earning his bachelor’s degree in biology and chemistry. He went on to pursue a Ph.D. in botany at North Carolina State University.

“It was a culture shock. The first semester was hard. More than graduate school hard. You are finding your identity at 21 and not sure what you are doing,” he said.

It was tough mentally and stressful — adjusting to a new environment while experiencing microaggressions. He decided to leave the program with his master’s in plant cell biology and biotechnology.

From plants to viruses

With supportive people by his side, Rivera–Serrano was offered a program transfer. He interviewed with a virologist, and she offered him a rotation position in her lab.

“The university actually extended my fellowship for a year just to give me freedom to find a lab. I rotated with her and loved it…my first and only rotation. Ironically, her lab was at a vet school,” he said.

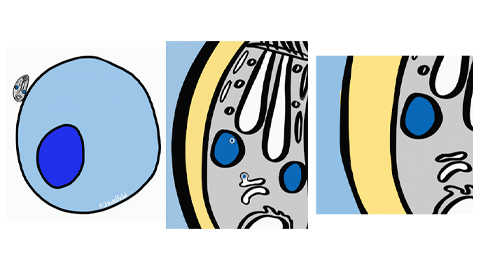

In 2016, he earned his Ph.D. in comparative biomedical sciences, where he studied how cardiac cells respond to viral infections and the immune response.

After graduating, he did a two-year postdoctoral fellowship at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he focused on hepatitis A viral entry and egress, and then took a one-year postdoc position at the University of California, Davis, where he focused on developing a synthetic guide gRNA-based CRISPRi system. Then, returned to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and become a research associate in virology.

A day in the life

While in this position, the pandemic started. He used this time at home to explore what a life outside of academia could look like. He made a list of non-negotiables, which included having time, flexibility and creativity.

Once the university reopened, he realized he wanted to be home. While still employed, he connected on Twitter with scientists who write for a living to learn about their careers. They connected him to scientists who worked in project management, industry, and science and medical writing.

He now has several part-time jobs that bring in roughly the same income he was getting before. Three of his jobs involve handling social media for science journals and magazines: He is a social media specialist for the American Scientist magazine, social media fellow for the journal Molecular Biology of the Cell and social media intern for the Genetics Society of America. He reads articles and writes posts about them for Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.

“This means taking an eight-page paper and condensing it to tweet or making it pretty for Instagram. I spend my weeks just reading 70 to 80 articles from different magazines, scheduling and finding the authors and institutions to tag on Twitter,” he said.

In addition, he is a contributing editor for the American Scientist magazine, for which he edits and translates articles into lay terms. And he's a freelance writer and consultant in virology for companies.

“I told myself that I was going to make a decision by this summer about whether I wanted to have a full-time job or stay. I still like it because it gives me all my non-negotiables,” he said.

Advice for scientists seeking a nonacademic pathway

Rivera–Serrano encourages scientists who want to make the switch to take time to reflect. With the right strategies, he was able to use his virology expertise and science communication skills to make his move. Here are his tips:

Use your transferable skills: As a scientist, you have many skills to offer. Whether it is knowledge-based (your field expertise), communication (writing papers and presenting at conferences), leadership (training and mentoring students in the lab) or organizational (doing inventory for your lab) — these are all highly valuable skills.

Connect with others while still employed: Connections come across differently while you are in the inside. Use this access to meet with program directors or officers across your university/organization. Set up Zoom coffee chats with nonacademic scientists and those outside your field.

Book time on your calendar: Dedicate time without technology. Find your list of non-negotiables: what suits your lifestyle, skills and personality.

Post your research and work online: Your digital footprint matters. Share your presentations, workshops and projects. This helps build your brand and gives you a platform to share ideas.

Use Twitter: Twitter helps breaks the ice before cold emailing someone. He used Twitter to follow scientists in virology, industry and science communication and build connections. This helped him land the positions he has today.

To find out more about Rivera–Serrano’s work, follow him on Twitter and check out his website.

How academic institutions can help

Rivera–Serrano understands how difficult it can be to navigate careers outside of academia. Science is often rewarded in terms of publications and impact factor, but not every scientist who wants one will land an academic job. Here are ways academic institutions can make this transition easier.

Get on social media: Trainees and emerging professionals want to feel supported both online and offline. When principal investigators and other leaders set the example by embracing social media and normalizing having difficult conversation (i.e., work/life balance, racial and gender inequalities, etc.) it makes a difference. "If a dean is only interacting with deans, you will never see the complaints that a grad student is having. It's two-way. As trainees, we are doing our best, by vocalizing and normalizing the issues, but who's listening is a different question," he said.

Encourage trainees and professionals to use their online platforms: Simply adding social media handles to the laboratory and academic websites builds community and drives more traffic.

Embrace different areas to communicate research: Science communication is a tool to maximize audiences when used correctly. "Why are we not rewarding students that are doing podcasts? That should be valued. If someone doesn't want to be an academic and they want to do a career in science communication, why is the qualifying exam is not a scicomm exam — like developing a podcast?" he said.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Careers

Careers highlights or most popular articles

Sketching, scribbling and scicomm

Graduate student Ari Paiz describes how her love of science and art blend to make her an effective science communicator.

Embrace your neurodivergence and flourish in college

This guide offers practical advice on setting yourself up for success — learn how to leverage campus resources, work with professors and embrace your strengths.

Upcoming opportunities

Apply for the ASBMB Interactive Mentoring Activities for Grantsmanship Enhancement grant writing workshop by April 15.

Quieting the static: Building inclusive STEM classrooms

Christin Monroe, an assistant professor of chemistry at Landmark College, offers practical tips to help educators make their classrooms more accessible to neurodivergent scientists.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.

Exploring lipid metabolism: A journey through time and innovation

Recent lipid metabolism research has unveiled critical insights into lipid–protein interactions, offering potential therapeutic targets for metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases. Check out the latest in lipid science at the ASBMB annual meeting.