Taking a first bite of biochemistry

Amid the thousands of grad students, postdocs, early-career investigators and tenured professors streaming into the Seattle Convention Center for Discover BMB last month was 17-year-old Kimy Hernandez, a high school student.

Hernandez is a senior at Longmont High School in Colorado and — like most of the more than 100 teenagers who attended the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2023 meeting — a member of a Students Modeling a Research Topic, aka SMART, Team. Their mission: to present group research projects developed with their high school science teachers and, in many cases, with working scientists.

Inspired by SMART Team’s meld of 3D modeling, analysis and research, Hernandez, who uses the pronoun they, is poised to become a first-generation college student. They plan to study molecular biology; their parents, both Mexican immigrants, were unable to study beyond high school.

“SMART Team really served as a catalyst for my love of science and for pursuing it as a career,” Hernandez said.

This year’s SMART participants hail from 21 schools in nine U.S. states and one Canadian province. As recently as 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, SMART Team and a sister program, Modeling a Protein Story, known as MAPS, sponsored 63 teams across the continent.

“The only regret I have about SMART Team is not starting earlier,” Hernandez said. “SMART really provides you with a diverse group of people who teach you a lot about yourself.”

Witnessing the world of science

Veteran attendees might experience ASBMB conferences as a collegial yearly break from their professional routine, but for high schoolers, the camaraderie can come as a revelation.

Tim Herman started the SMART Team program in 2001 and began bringing participants to the conference in 2004. “The most powerful thing that happens is in the opening session,” he said of the annual meeting. “There will be SMART Teams in the audience, and they see people greeting each other. High school students can imagine themselves as future members of this community of science.”

When they make their SMART Team presentations, students experience the realities of research life, said Luke De, a long-time teacher with SMART Teams at private schools in New Jersey and California. This includes giving talks about their studies and fielding sharp questions.

“Kids have to get in front of M.D.s and Ph.D.s,” De said. “We harp on the idea that science is a conversation, but rarely do kids get to experience that conversation.”

At the ASBMB meeting, that passionate exchange comes alive.

“We’ve always been focused on introducing students to the real world of science, including publishing and presentation,” Herman said of SMART Teams. The conference “gives these high school students the chance to stand alongside undergraduates and present their work.”

A strength of any profession lies in its ability to recruit the next generation of practitioners, Herman pointed out. “We have former SMART Team students who are now running research labs and interested in working with local SMART Teams,” he said.

At Longmont High, Chris Chou, co-coordinator of the school’s Medical and BioScience Academy, has been offering the SMART Team program for 11 years. She tells a story that illustrates the conference’s impact.

During a SMART Team visit to the University of Colorado Boulder about six years ago, high schooler Maya Lippard Blau became smitten with X-ray crystallography for the study of proteins, Chou said. At the 2017 ASBMB annual meeting, Blau met Stephen White, a scientist doing this work at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee. The two swapped contact information, and the teenager went on to a 2018 summer research internship with her new mentor.

“Instead of just reading about x-ray crystallography, she was doing it,” Chou said, “and that launched her interest in science.”

Blau followed her passion through college and into an M.D./Ph.D. program in infectious diseases at the Medical College of Wisconsin. “Because I was close to both the medical and the research side, I realized I couldn’t picture my future career without both,” she said.

Building student skills in biochemistry

In the short term, SMART Team means “students having the opportunity to dive deeper into topics only touched on in courses,” Chou said. “They get to interact with professors, visit research laboratories.”

Longmont students have taken a field trip to a Pfizer laboratory in Boulder, Colorado, to witness cancer drug research and visited the Biomolecular X-ray Crystallography Facility at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Kelly Lubkeman, co-coordinator with Chou of the academy at Longmont, echoes her colleague’s enthusiasm. Her students normally would “get the skills and basics in their classes but don’t get the exposure to what a research scientist really does on a daily basis,” she said. SMART Team helps fill that gap.

Longmont students in the program now are studying and modeling the tumor suppressor protein p53. Mutations at several points in this macromolecule have been linked to human cancers — and at least one is a potential drug target.

“They call it the holy grail,” Lubkeman said. “If we could successfully target a drug for that mutation … it will open the door for a lot of other cancer drug treatments.”

Across the country at Mahtomedi High School in Minnesota, biology teacher Jim Lane has witnessed social and cognitive growth in his SMART Team students.

“I see kids coming out of their shell but also developing discourse skills and collaboration,” Lane said, adding that his students begin to forge the intellectual skills needed for research. “They are constantly rethinking, iterating and reflecting on their learning. The collaborative atmosphere is what really pulls the team together.”

SMART Team veteran Luke De believes the program can lead students to the heart of science as they gain confidence in their own curiosity.

“Kids think the crazy ideas they have are frivolous,” De said, “but what they learn is that those crazy ideas are the things that make scientific research.”

Expanding the research rainbow

Abi Ferguson, 17, another Longmont senior, has been exploring the fine points of beta adrenergic receptors, which affect the function of smooth muscle and digestion. She has noticed the many medications, such as beta blockers, that interact with the protein she is studying.

While exploring her macromolecules, Ferguson got hooked on biology. She learned to find and decode crucial insights in research studies, gleaning more details about her proteins.

“SMART Teams really pivoted me to science,” Ferguson said. “This is what I want to do.”

Greta Wedel, also 17 and a senior at Longmont, said she’s learned to read scientific journal articles and help her teammates write research abstracts. With these science-based skills, Wedel envisions a different career path but one that also demands high-level analysis and writing: the law.

“No matter who you are, how you learn or what you’re interested in, there’s something valuable to find in SMART Teams for everyone,” Wedel said.

Their classmate Hernandez has found it challenging to forge constructive relationships among SMART Team members. Yet, in their classmates’ differences, they have learned, lie the group's collective strength, as members take on specific tasks — from model making to reading peer-reviewed research studies.

“There’s a lot of people with lots of learning styles,” Hernandez said. “Everyone’s able to specialize.”

SMART Teams are largely female, including young women of color — a striking contrast to the historic underrepresentation of women and marginalized groups in the biological sciences.

“What we’re doing … is exposing more students to science research, because science is stereotypically done by white males,” Chou said. “We’re trying to recruit a more diverse group of students who are traditionally underrepresented in science to pursue future careers in science.”

The team aspect of the program plays to adolescent strengths and interests, as peer relationships gain importance in their social and academic development, noted SMART Team coordinator Mark Arnholt. “You end up with students from very different social backgrounds working together and creating long-lasting friendships,” he said.

Tracing the program’s ripples

Blau looks back on SMART Team as a foundation for the science she studies now. “I ended up learning to read scientific papers,” she said. “It felt like I had a huge advantage in college and beyond.”

For Abbey Kastner, 25, a doctoral student in neuroscience at the Medical University of South Carolina, the path to a science career started with SMART Team. She traces her first steps on that path to a talk on the program during freshman orientation at Hartford Union High School in her Wisconsin hometown. That introduction, Kastner said, “made me realize there’s jobs out there that involve research, and I can do them.”

With the guidance of Arnholt, then a teacher at Hartford Union, Kastner’s SMART Team built a model of CYP17A1, a gene on chromosome 10 involved in drug metabolism and lipid synthesis.

“We worked with researchers at Marquette University,” Kastner said, “which is something most high schoolers don’t have the option to do.”

In 2016, Kastner’s senior year, her team project won a first-place award in a statewide spring competition at the Milwaukee School of Engineering. But the crucial takeaway from SMART Team was bigger than one prize.

“The first thing was confidence,” Kastner said.

Her burgeoning ambitions led to a summer internship at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Kastner went on to study biochemistry and neuroscience at the University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire. There she spent four years as a student researcher and two years as a lab manager.

“I’m grateful for all the mentorship I’ve had because that is not extended to all students and certainly not to all female scientists,” Kastner said.

Looking back, she said her first exposure to SMART Team was a catalyst for her science career: “It’s crazy that one conversation can change everything.”

Blau and Kastner are case studies in the way SMART Team can help steer young people toward a research career.

“SMART Teams, by offering high school students the chance to engage with basic scientific research, is inspiring the next generation of scientists,” said Blau.

In addition to becoming a scientist, Kastner wants a role in the public conversation about scientific research. “I feel like there is a gap between what the public knows and what scientists do in the lab,” Kastner said. “I want to be part of communicating between these audiences.”

SMART Team program brings research to life

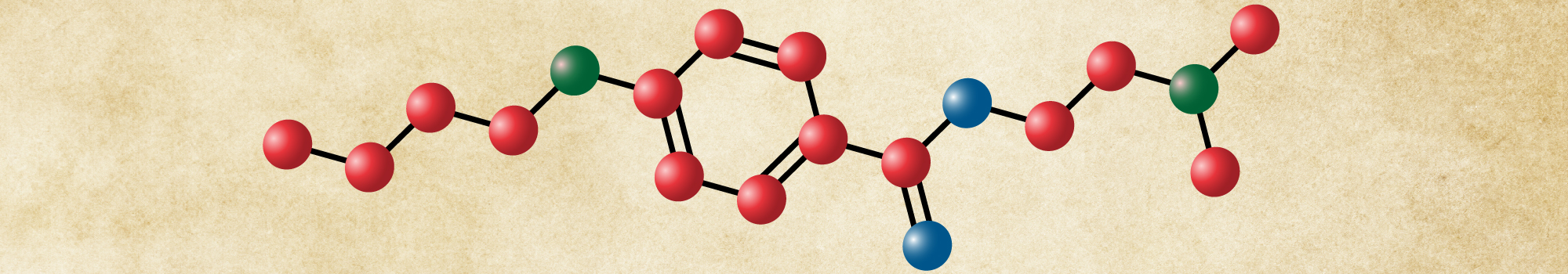

When 3D printing was a new invention, Tim Herman saw its potential as a tool for modeling macromolecules with crucial roles in living things — and for strengthening secondary science education.

"I envisioned this 3D printing technology as the key to introducing high school students to the invisible molecular world,” Herman said. “Models give meaning to words.”

Multiple research studies support the idea that 3D physical models help engage students and that students prefer them to other forms of learning.

While on the faculty of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Herman learned that the Milwaukee School of Engineering had a rapid prototyping center. He founded the Center for BioMolecular Modeling, or CBM, at the engineering school in 1998 and went on to launch 3D Molecular Designs, a family-owned company, the following year.

In the early 2000s at CBM, Herman led teachers in a new course, “Genes, Schemes and Molecular Machines.” They 3D-printed a ribosome, the cell structure that synthesizes polypeptides. The ribosome recently had been described for the first time by Thomas Steitz, a Yale University professor who would go on to win the 2009 Nobel Prize in chemistry with two colleagues.

“The teachers were the ones who told us they wanted their students to have the same experience,” Herman said.

And so Students Modeling a Research Topic, or SMART, Team was born in 2001 at the Milwaukee School of Engineering. In December 2021, the program moved as CBM merged into 3D Molecular Designs.

SMART Team garnered long-term support through the Science Education Partnership Award from the National Center for Research Resources at the National Institutes of Health. It also has received grants from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Each high school pays an annual $250 participation fee that helps fund technical support in the form of an experienced science educator and 3D model printing.

For high school students, the program begins with a training phase that’s followed by a research phase. At the heart of the experience is the macromolecular model.

Mark Arnholt is a veteran science teacher and now coordinator for SMART Team. “The second they’re holding that physical model … is one of those ‘aha’ moments,” Arnholt said. “They can finally understand why this protein is interacting the way it does.”

Students start with the known story of a protein, model making, drafting an abstract, and reading both primary and secondary sources. Then they have the chance to devise their own research project.

“Science is all about asking questions, and once you’ve identified those questions, you can start to chase them down,” Arnholt said. “A lot of the questions don’t have answers, and those are the ones you want to pursue.”

Luke De was a director of independent research projects at the Pingry School in Basking Ridge, New Jersey, in the early years of the program. “SMART Teams did something genius: It paired kids with a researcher and forced them to tell a story,” De said. “All the stories were tangible; you were literally building a model.”

And, in addition to being a learning tool, protein modeling helps high schoolers shine a light on the roots of human illnesses, Arnholt said. “Slowly and steadily, students realize that every disease can be traced back to a protein that is misbehaving.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Careers

Careers highlights or most popular articles

Mapping proteins, one side chain at a time

Roland Dunbrack Jr. will receive the ASBMB DeLano Award for Computational Biosciences at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Exploring the link between lipids and longevity

Meng Wang will present her work on metabolism and aging at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Upcoming opportunities

Calling all biochemistry and molecular biology educators! Share your teaching experiences and insights in ASBMB Today’s essay series. Submit your essay or pitch by Jan. 15, 2026.

Defining a ‘crucial gatekeeper’ of lipid metabolism

George Carman receives the Herbert Tabor Research Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Building the blueprint to block HIV

Wesley Sundquist will present his work on the HIV capsid and revolutionary drug, Lenacapavir, at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, in Maryland.

Upcoming opportunities

Present your research alongside other outstanding scientists. The #ASBMB26 late-breaking abstract deadline is Jan. 15.