When Batman meets Poison Ivy

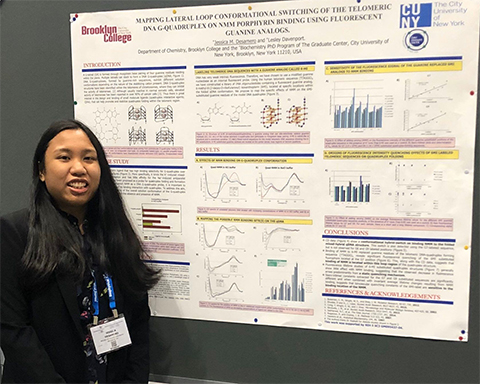

Presenting my research to my Ph.D. thesis committee was straightforward. However, explaining my work to an 8th grade-level audience at a general science communication event was challenging. No actual 8th-graders were present, but the audience had very little scientific knowledge.

So, I unleashed my creative, nerdy side: comparing my research to a hero–villain battle. At the time, I studied the role of DNA secondary structure in halting cancer cell growth, which helps prevent further tumor progression. In my talk, I compared the DNA to the superhero Batman and cancer to the villain Poison Ivy. In my imaginary battle, Batman uses his specialty gadgets to stop Poison Ivy and her plants from taking over the city.

I took scicomm to another level, and I enjoyed every minute of it. But I didn’t get to this point overnight.

I got my start in science communication when I was an undergraduate. Stony Brook University had a biannual science journal for undergrads by undergrads about research on campus. I worked on two news pieces.

At this point, writing wasn’t new to me — I already wrote for the arts and entertainment section of the school newspaper — but reporting on topics related to biochemistry merged my love of writing and science, and I instantly felt a connection.

Years later, in my fourth year of grad school, I found volunteer science writing. I started with OncoBites, a blog that reports the latest cancer research in short, bite-sized articles, and then got involved with ASBMB Today. These experiences rekindled and reinforced my love for scientific storytelling.

And I learned scientific translation. I had to write about complex scientific topics in a way that an undergraduate student could understand. This was an art form in and of itself.

In 2023, I presented my research at two scicomm events where most audience members were graduate students in biology and neuroscience. They weren’t familiar with my research or even with biochemistry. I really enjoyed this challenge. To explain my concepts, I created analogies and accompanying simple, easy to follow visuals. In one of my slides, I presented the method behind my research as an origin story, which I laid out in comic book-style panels. I learned that connecting science to something tangible in the real world that people love, like comics, can be a powerful tool.

Another thing I love about scicomm is that it gives me a chance to learn from amazing people.

During a scientific writing internship, I interviewed two cancer survivors who told me about their personal journeys and their advocacy efforts to spread cancer awareness. I was particularly moved by what they said. They encouraged people to be informed and unafraid, shared words of support and reminded people that they are not alone. It was an honor to tell their story.

Scicomm challenges and inspires me, and I truly value it. The more I practice it; the more I love it. Perhaps I’ll meet Batman and Poison Ivy, or another dynamic superhero duo, again during my scicomm journey.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Careers

Careers highlights or most popular articles

Upcoming opportunities

Apply for the ASBMB Interactive Mentoring Activities for Grantsmanship Enhancement grant writing workshop by April 15.

Quieting the static: Building inclusive STEM classrooms

Christin Monroe, an assistant professor of chemistry at Landmark College, offers practical tips to help educators make their classrooms more accessible to neurodivergent scientists.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.

Exploring lipid metabolism: A journey through time and innovation

Recent lipid metabolism research has unveiled critical insights into lipid–protein interactions, offering potential therapeutic targets for metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases. Check out the latest in lipid science at the ASBMB annual meeting.

Hidden strengths of an autistic scientist

Navigating the world of scientific research as an autistic scientist comes with unique challenges —microaggressions, communication hurdles and the constant pressure to conform to social norms, postbaccalaureate student Taylor Stolberg writes.

Upcoming opportunities

The countdown to #ASBMB25 is on! Visit our annual meeting website to start adding special sessions, keynote lectures, scientific symposia and more to your personal schedule.