Weaving social innovation and scientific methods for a bright future

My native country is small, just a little larger than Colorado, and underdeveloped. Although the United Nations Development Programme ranked us second to last in the world for education in 2009, I believe it is a country with a better future. For the past eight years, through a foundation I call Teêbo, I have been working from the U.S. to help make that future.

My parents never made it past primary school. Through their faith, they showed what it means to love and give with very limited resources. We were poor, yet they joyfully practiced true hospitality. Sometimes more than 14 people lived in our house; we didn’t have enough, but my parents welcomed others who needed help, offering a place to stay or a meal. Continually exposed to this spirit of giving, I wanted to help improve other people’s lives.

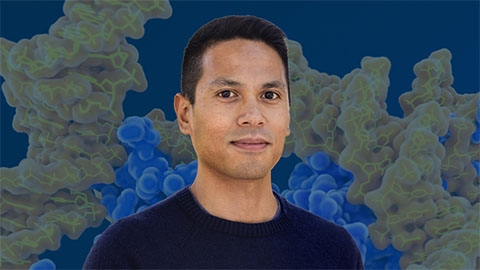

Pingdewinde Sam, a Ph.D. candidate in the department of cellular and molecular physiology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, founded Teêbo, a nonprofit organization, to help people in need in his native Burkina Faso.James Osei-OwusuWhen I was growing up in a small district of Ouagadougou, the capital city of Burkina Faso, my parents made sacrifices that showed me the importance of education, sharing knowledge and giving back to my community.

Pingdewinde Sam, a Ph.D. candidate in the department of cellular and molecular physiology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, founded Teêbo, a nonprofit organization, to help people in need in his native Burkina Faso.James Osei-OwusuWhen I was growing up in a small district of Ouagadougou, the capital city of Burkina Faso, my parents made sacrifices that showed me the importance of education, sharing knowledge and giving back to my community.

My childhood in one of the poorest countries in the world shaped my mind. My parents made sacrifices to send me and my three siblings to school. I was sent home many times during primary school for not paying the full $70 tuition. Public schools were full, and my grades were not excellent enough for a national scholarship, but my parents never gave up. They encouraged me to do well in school, and I realized then that knowledge is so powerful no one should be deprived of it.

Over the years, seeds were planted in my heart to create learning opportunities for those who couldn’t afford school and, above all, to mentor and help those in need.

The land of opportunity

Through a green card lottery, I immigrated to the United States at the age of 19. My older brother Barkwendé Bonaventur, who dreamed of coming to the U.S., registered himself in the U.S. Diversity Immigrant Visa Program and forcibly took my weekly allowance of 500 CFA francs (the equivalent of $1) to register me as well. The registration was free, but my precious dollar paid 60 cents for one hour at a local internet café to complete the online application and 40 cents to scan in my profile picture. The average Burkinabé lives on less than $1 per day.

I was angry when my brother took my money. He applied two years in a row before me but never was selected, and to this day, he still applies. I wasn’t interested, but he believed I had a chance. It turned out to be a wonderful opportunity that changed my life and created financial sustainability for my family and many people in my community.

Without any of my immediate family, I moved to San Francisco. I was a young immigrant from a developing country who spoke no English. Fortunately, my wonderful and supportive uncle Beniwendé George Kabré lived there and was an exceptional mentor to me. A sixth-grade student, age 12, in the Vipaolgo Village shows off school supplies she received in October 2017 through the Teêbo Exam Prep Program. The supplies were donated by the Science Education Partnership and Assessment Laboratory at San Francisco State University.Teêbo

A sixth-grade student, age 12, in the Vipaolgo Village shows off school supplies she received in October 2017 through the Teêbo Exam Prep Program. The supplies were donated by the Science Education Partnership and Assessment Laboratory at San Francisco State University.Teêbo

Because I was studious and worked hard, my chemistry teacher in junior college, Ronald Drucker, advised me to apply to the National Institutes of Health Bridges to the Baccalaureate Research Training Program in 2011. I seized the opportunity and was accepted. Since then, I have been guided and trained by incredible mentors at the City College of San Francisco; San Francisco State University; the University of California, San Francisco; and Johns Hopkins University. I am now a fifth-year Ph.D. candidate in cellular and molecular physiology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. But I never forgot where I came from.

Making a difference

On Christmas Day 2005, my dad taught me a lesson about the impact of a small action of generosity. It was a difficult year for my family. My father didn’t make much profit from his jewelry shop, and my mother was medically disabled. My parents always gave us new clothes and shoes on Christmas, so I went to my dad expecting these gifts. He said that he didn’t make enough money to get us new clothes. I went to my room crying.

My dad called me back a few minutes later and gave me two envelopes with less than $10 in each. He told me to take them to two neighboring families from my childhood church. I was confused — he didn’t make enough money to buy clothes for us, but he had some to share? The first family was a widow with seven children. When I handed her the small gift, the emotions in the house changed; the family was overjoyed and super excited. The second family responded in the same way, and this transformed my bitterness to joy. From that lesson in sharing, I learned that a small act of generosity could make a big difference.

I had my first real job in 2008 after I moved to San Francisco. My people in Burkina Faso struggle with basic needs such as education, food, clean water and sanitation. To help address these needs, I started to save and frequently wired money for my family to support those who struggled to survive. In 2011, I went home for the first time since moving to the U.S. What I saw saddened me, and I felt called to offer hope to Burkinabés who lack basic needs.

We named our organization Teêbo, which is the word for hope in Mooré, the national language in Burkina Faso. The organization focuses on eliminating poverty and hunger, increasing the literacy rate, combating water-related diseases by drilling wells, and improving health in Burkina Faso. In 2012, it was incorporated as a 501(c) 3 U.S.-based nonprofit organization. Farmers in the Goennega village show samples of their corn harvest at an August 2015 meeting to measure the impact of Teêbo’s End Starving Season agricultural program.Teêbo

Farmers in the Goennega village show samples of their corn harvest at an August 2015 meeting to measure the impact of Teêbo’s End Starving Season agricultural program.Teêbo

More crops, more education

Teêbo is run by volunteers here and in Burkina Faso. Our U.S.-based board of directors helps us secure financial resources. In Burkina, a local team runs day-to-day activities, while in each village we choose four or five ambassadors to represent us and be our eyes and ears.

With Teêbo, we have built programs to engage, equip and empower Burkinabés in rural areas. Our End Starving Season program aims to increase crop yields that sustain thousands of lives. We equip hardworking farmers with animal-powered plows and bags of fertilizer, and we teach them new farming techniques.

In Burkina Faso, students must pass a national exam to enter the seventh grade, but many fail and drop out of school. Only 29% of adults are literate, and just 2% of all Burkinabés have a secondary education. My team has developed an Exam Prep Program for sixth-grade students in villages. The six-month program provides private tutoring, school supplies, meals and mentors. At the end of the pilot program in 2014, the first school more than tripled their success rate, from 30% to 98%. Since then, we continue to register incredible success rates, sending both girls and boys to school.

Most schools in Burkina lack basic teaching supplies. In 2016, I co-founded EDEN School with my wife, Wendpagnanda Christiane.

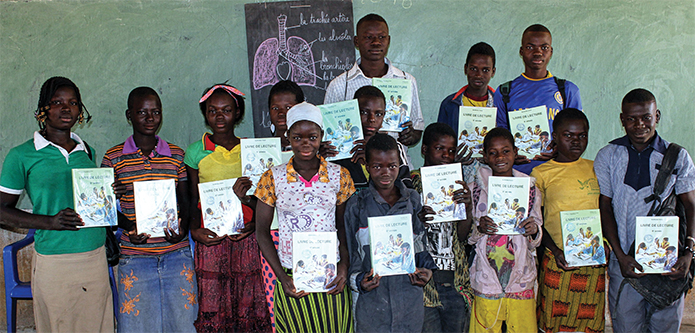

We aim to advance knowledge using the 5E model (engage, elaborate, explain, evaluate and examine) that I learned at the Science Education Partnership and Assessment Laboratory at San Francisco State University. Our curriculum and teaching strategies encourage teamwork with pre- and post-lecture assessments. We plan to implement STEM education through collaborations with scientists and teachers in the field and here at Hopkins. The Teêbo Exam Prep Program provided these sixth graders at Primary School A in Goumsin village with new required French reading books in October 2018 to help them prepare for the national exam to enter seventh grade.Teêbo

The Teêbo Exam Prep Program provided these sixth graders at Primary School A in Goumsin village with new required French reading books in October 2018 to help them prepare for the national exam to enter seventh grade.Teêbo

Weaving science and service

In my research lab, my mind often leads me to ask how my experiments can have a positive social impact. My service work is woven with my scientific research. My indelible long-term goal always has been to improve human health through improving quality of life and saving lives. This is constant whether I am wearing the hat of a social entrepreneur or a scientist.

I regularly apply the scientific method as founder and executive director of Teêbo. Our strategies to help the Burkinabés are intertwined with the scientific process of making discoveries. It starts with background research, collecting data in a new village. From that preliminary data, my team and I meet and launch a pilot program, which we then closely monitor to assess its effectiveness. Through measuring and analyzing the impact of the implemented programs, we can report back to partners and donors; this is the publication stage for us.

I have been able to use my research skills to help grow Teêbo and EDEN School. I look forward to a future when I’ll contribute actively to enriching lives not just in my naturalized and birth countries but other countries as well, making our world a better place through my experiences in biomedical research and social innovations.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Meet the editor-in-chief of ASBMB’s new journal, IBMB

Benjamin Garcia will head ASBMB’s new journal, Insights in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, which will launch in early 2026.

Exploring the link between lipids and longevity

Meng Wang will present her work on metabolism and aging at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Defining a ‘crucial gatekeeper’ of lipid metabolism

George Carman receives the Herbert Tabor Research Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Nuñez receives Vallee Scholar Award

He will receive $400,000 to support his research.

Mydy named Purdue assistant professor

Her lab will focus on protein structure and function, enzyme mechanisms and plant natural product biosynthesis, working to characterize and engineer plant natural products for therapeutic and agricultural applications.

In memoriam: Michael J. Chamberlin

He discovered RNA polymerase and was an ASBMB member for nearly 60 years.