With a little help from my friends

“He is going to be so upset.” That was my first thought when the head nurse in the emergency psychiatric ward told me they needed to notify my emergency contact of my situation. “He” wasn’t my PI. Nor was he my father or any other blood relative. He was my friend.

It was my fourth year of graduate school, and things were not going well. My project refused to cooperate, my relationship with my PI was strained, and I simply couldn’t handle it. I had made an appointment to speak with a therapist, and within half an hour of our meeting, she was escorting me to the hospital across the street. I was terrified. But as traumatic as the whole ordeal seemed, I was most concerned how my best friend, now an objectively successful postdoc at MIT, would react to the news.

A recent report in the journal Nature Biotechnology shows that my story is not uncommon among my peers. Around 40 percent of students surveyed reported experiencing depression, and a similar number reported anxiety. The study also suggests that these experiences are correlated with students having negative feelings about relationships with their mentors.

Graduate students also experience an inordinate amount of stress. I know plenty of students who report working 50-plus hours in a week, and many take on additional debt to make ends meet when their stipends fall short. Often, they’ve entered their program right after college, and this is their first full-time job experience. On top of that, they likely have moved to an unfamiliar place, crippling whatever local support system they had before starting the pursuit of their advanced degree. More is expected of them than ever before, and they try to meet those expectations with as small a support structure as they’ve ever had.

So what can graduate students do to overcome this common and untenable situation? In addition to others detailed in this issue of ASBMB Today, I’d like to put forth a resource that rarely is talked about in any depth: friendship.

When I was released from the hospital the next morning, I was greeted by some very concerned text messages from my friend. After I told him I was home, he dropped his lab work and came to meet me at my apartment. I was waiting outside on the stoop, and he sat down next to me. What followed was a long silence, which I broke:

“Thanks, man.”

After his laughter subsided, he responded, “No problem.”

We talked for a long time, and after a while, it dawned on me just how much I appreciated this person. He, along with the rest of the friends I made in graduate school, meant more to me than I knew — until that very moment.

Throughout the next few weeks, I made it a point to talk to each one, telling them what I was going through and that I appreciated them. I was dumbfounded by their responses: offers of support and love, without fail or hesitation. My story wound up having a happy ending, and I’ve compiled some advice here on friendship so that yours can too.

Advice

Before I continue, I’d like to plead with anyone who is having thoughts of self-harm to talk to someone about it immediately. There are people who want to help and care about you. Which brings me to my first bullet point:

| • | Psychiatrists, therapists and mental health counselors can help you. And a psychiatrist can work with you to treat any neurochemical imbalances you may have. If you have an opportunity to see a professional, and you think you need to, I urge you to take advantage of it. |

| • | We’re all in this together. Your classmates and older graduate students have some understanding, at least, of what you are feeling. Although it can be anxiety-inducing to introduce yourself to someone new, remember: they’re in the same position you are. |

| • | Don’t be afraid to tell your friends how you feel. The strongest foundation of any relationship is honesty, and friendships are no different. When things are going well, tell them. And when things aren’t great? Tell them. Your friends care about you, and they’ll help you if they can. |

| • | It’s a two-way street. Your friends will need you as you will need them; be sure to listen to and care for them, if doing so doesn’t overly tax you. It’s always OK to say no if you’re uncomfortable, but reciprocal effort in any relationship is critical. |

| • | Friendship doesn’t have to mean hanging out. Time and money are short in graduate school, but luckily, friendship doesn’t require either of those things. Coffee breaks taken together and exchanged text messages are great ways to catch up and remind yourself that you are not alone in this. That said … |

| • | Make special plans together. Planning and taking vacations together cuts down on costs and promotes a healthy work-life balance, and it is a more concrete commitment to time away from the lab than “I’ll try not to go to the lab this weekend.” Additionally, spending time with people you care about will reinforce the bonds between you, and all involved will be better for it. |

No one is an island, and no one can do this alone. Make friends, care for them and build on each other’s strengths. Lean on them and offer your hand when they need it.

Even though graduate school threatened to capsize me, my friends were my bulwark.

And they still are.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

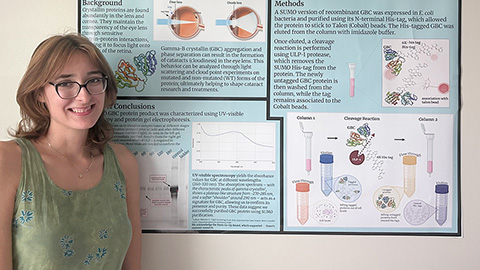

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.